LGBTQ Family Advocacy at School

This paper presents a set of testimonies from three LGBTQ families about the advocacy work they took up in their schools. The stories they share are part of an interview study undertaken from 2014–2020. Each family responded to the cisheteronormative cultures of their schools by challenging ideas teachers and principals held about gender, sexuality, and families and some of their everyday practices. The advocacy work the families undertook is discussed through two analytic lenses, the Triangle Model (McCaskell, 2005; Thomas, 1987) and intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989), demonstrating how middle-class economic resources and professional education were key to parents’ success.

Keywords: family, gender, LGBTQ, sexuality, verbatim theatre

This paper reports on the ways LGBTQ, gender unique, and non-binary parents and students advocate for themselves in Ontario public schools. The research we share here comes from a multi-year interview study undertaken with 37 LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer)[1] families living in six different cities in the Canadian province of Ontario as well as in the suburbs and rural communities surrounding them. The study, undertaken between 2014 and 2020 examines a variety of strategies LGBTQ families use to work with schools that don’t expect (hicks, 2017) or anticipate the arrival of their families and children.

Issues Facing LGBTQ, Gender Unique, and Non-Binary Parents and Students at School

A two-decade review of the literature about the experiences of LGBTQ and gender unique, non-binary parents and students in North American public schools reveals that many families deal with issues such as: (1) securing acceptance and support from the teachers and administrators at their children’s schools (Brill & Pepper, 2008; Casper & Schultz, 1999; Goldstein, 2014); (2) effectively responding to verbal and physical harassment at school (Epstein, 2009; Epstein et al., 2013; Taylor & Peter, 2011); (3) securing support from their families of origin and families of choice during their children’s school years (Boluda, 2005; McNeilly, 2012); and (4) challenging the internalized homophobia children feel when they are marginalized at school (Taylor & Peter, 2011; Waring, 2013). Research about the experiences of LGBTQ families attending Catholic schools in Alberta and Ontario (Callaghan, 2007) also suggests that these issues may be exacerbated by policies about homosexuality and same-sex attraction that guide Catholic schooling practices in Canada (see, e.g., Assembly of Catholic Bishops of Ontario, 2010; Episcopal Commission for Doctrine, 2011).

Teachers and principals who are knowledgeable about the experiences of LGBTQ families in schools can be important resources for LGBTQ families affected by issues such as harassment, discrimination, and marginalization. However, educational research indicates that teachers and principals often have naïve, negative, and potentially harmful opinions about students and families who are different from their own (Goldstein, 2005, 2010, 2014, 2019, 2021a, 2021b; Hollins & Guzman, 2005; Robinson, 2005; Robinson & Ferfolja, 2001, 2002). LGBTQ families who are currently working with teachers and principals to create safe and respectful learning environments for their children have much to teach other educators about the kind of support that is needed to create positive school experiences for LGBTQ students and families. Stories of LGBTQ families’ work with schools can also assist other LGBTQ families to better understand and respond to the complex issues and situations they face in their own schools (Brill & Pepper, 2008; Snell, 2013).

The testimonies and stories shared in this paper respond the following research question: How are LGBTQ families working with teachers and principals to create safer and more supportive learning spaces for their children? To answer this question the research team, led by Principal Investigator Tara Goldstein from the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto, conducted 35 video and 2 audio interviews with the 37 families and then analyzed both the issues and conflicts they face in schools and the work they do with teachers and principals to create safer and more supportive learning environments for their children (Goldstein, 2019, 2021a, 2021b; Goldstein et al., 2018). In order to share our findings the research team has curated, tagged and uploaded the video interviews onto our website LGBTQ Families Speak Out (www.lgbtqfamiliesspeakout.ca) and used the interviews in workshops and courses for teachers, principals and families. We have also developed Out at School, a 90-minute multimedia theatre production which includes a verbatim theatre script, visual images and music based on the interviews that we have performed for numerous audiences and which can be used in workshops and performances for teachers, principals, families and communities and the general public (Goldstein et al., 2021).

Recent Canadian Legislation to Ensure Rights and Safety Of LGBTQ, Gender Unique, and Non-Binary Parents and Students at School

In response to strong activism by youth attending Catholic high schools (Houston, 2012), as well as a number of highly publicized suicides by LGBTQ youth who had experienced bullying in public schools, the Ontario government passed The Accepting Schools Act in 2012, which required all school boards in the province to (1) take preventative measures against bullying; (2) issue tougher consequences for bullying; and (3) support students who want to promote understanding and respect through Gay Straight Alliance (GSA) groups. Two years later, in 2014, the Ontario Human Rights Commission created a policy on preventing discrimination because of gender identity and gender expression. And three years after that, in 2017, an amendment to the Canadian Human Rights and Criminal Code (1) added gender identity and gender expression to the list of prohibited grounds of discrimination and (2) extended the protection against hate propaganda to any section of the population distinguished by gender identity or expression.

Our research team started interviewing LGBTQ families in the spring of 2014 to find out how, if at all, schools had begun to respond to both the Ontario 2012 Accepting Schools Act and the 2014 Human Rights policy to prevent discrimination on the basis of gender identity and expression.[2] We began with the understanding that LGBTQ, gender unique, and non-binary parents, children and youth often have to advocate to create safer, more supportive and more inclusive school experiences for themselves, so we also asked families about their advocacy work with teachers and principals at their schools. As the study progressed, parents who identified as heterosexual and cisgender as well as LGBTQ asked to be interviewed so that they could talk to us about the experiences of their gender unique, non-binary and trans children at school. For these parents, the 2014 Ontario Human Rights policy preventing discrimination of the basis of gender identity and expression was a very important document that could be mobilized to advocate for changes in their schools.

Methodology

The team describes our LGBTQ Families Speak Out research study as arts-based testimonial research. We understand the video and audio interviews we undertook with the families who participated in our study as testimonies. In their book Beyond Repair?, Alison Crosby and M. Brinton Lykes (2019) provide a helpful explanation of the practice of testimonio/testimony, reporting on the authors’ eight years of feminist participatory action research with Indigenous women in Guatemala seeking reparation for the violence they experienced in the early 1980s. They understand the practice of testimonio as a form of collective autobiographical witnessing that plays a role in developing and supporting international human rights. When the stories people tell about their experiences are linked to a group or community experiencing marginalization and oppression, Crosby and Lykes consider them to be testimonio/testimony. When stories are not linked to a group or community, they are considered autobiographies.

In applying Crosby and Lykes’s (2019) understanding of testimony to our research, the team sees the video interview clips that have been curated on the LGBTQ Families Speak Out website as testimonies. The video interview clips feature individual family stories that our research team has linked together thematically on the website to demonstrate that what has happened to one family has happened to others. Similarly, the monologues and dialogues in our verbatim theatre script Out at School are linked together thematically in 21 scenes. While the team have written about the findings of our study in traditional ways through journal articles, our multimedia performance Out at School shares our findings through the arts-based research method of verbatim theatre (Goldstein et al., 2021).

Data Collection

The 37 families who participated in the video interview study live in the cities of Toronto, Oshawa, Ottawa, Sudbury, London, and St. Thomas, as well as in suburbs and rural communities located nearby. Children and youth in these LGBTQ families attend(ed) school in both secular and Catholic publicly funded elementary and secondary schools. We recruited families through our own networks, and advertised for participants in local schools, LGBTQ publications, and LGBTQ venues. We also built online presence for the study by creating a website to document our research process, upload resources relevant to LGBTQ families as well recruit new participants.

Participation in the study was dynamic, and the criteria for participating expanded based on requests from the communities engaging with the project. To illustrate, when the team first began interviewing LGBTQ families in 2014 we restricted our interviews to parents who identified as LGBTQ themselves. However, at the Rainbow Health Conference in Sudbury in March 2018, the team met parents who identified as heterosexual and cisgender but were raising children who identified as LGBTQ. Some of these parents talked about their families as LGBTQ families because their children identified as LGBTQ. Others did not.

In the fall of 2018, when the team introduced the video interviews to the undergraduate students in Tara’s Equity, Activism and Education course at the University of Toronto, several students who identify as LGBTQ youth of color reported they would like to hear more families of color of talk about their experiences at school. The research team then intentionally recruited more families of color to participate in the study.

Data Analysis: The Triangle Model and Intersectionality

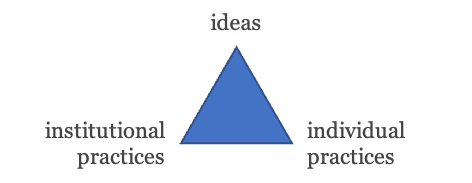

The team has worked with two key lenses to analyze the findings of our interviews. The first is a conceptual framework known as the Triangle Model (McCaskell, 2005; Thomas, 1987), which places people’s experiences of oppression into three categories and represents them in a triangular shape (see Figure 1). In this model, a particular form of oppression tends to begin with ideas: individuals act in a certain way because of the ideas they hold, and institutions function in particular ways because of the ideas held by the individuals who run them. Anti-oppression work also begins with the ideas people hold and the way they act on their ideas within the institutions they work in.

Figure 1

The Triangle Model

The second lens is the idea of intersectionality. While the term was first coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, the idea of intersectionality is not new. BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) women writers and thinkers before Crenshaw—for example, Anna Julia Cooper, Audre Lorde, Angela Davis, Frances Beal, Patricia Hill Collins and the women of the Combahee River Collective—all articulated the need to discuss race and gender together (Love, 2019), understanding that “multiple oppressions reinforce each other to create new categories of suffering” (Taylor, 2017, p. 4).

Crenshaw uses the term intersectionality to “deal with the fact that many of our social justice problems, like racism and sexism, are often overlapping, creating multiple levels of social injustice” (Crenshaw, 2016). To illustrate how racism and sexism overlap, Crenshaw described the situation of Emma DeGraffenreid, an African-American woman who claimed she was not hired for a job at a local car manufacturing plant because she was a Black woman. She brought her claim to court but the judge dismissed her suit, arguing that the employer did hire African-Americans and did hire women. What the judge was not willing to acknowledge, however, was that the African-Americans, who were hired for industrial and maintenance work, were men, and the women the employer hired for secretarial or front-office work, were white. Crenshaw named DeGraffenreid’s problem by using the analogy of the intersection of two roads, one road representing race and the other gender, with the traffic on those roads being the hiring policies and practices at the car manufacturing plant. The race road had policies and practices that encouraged the hiring of African-American men. The gender road had policies and practices that encouraged the hiring of white women. However, because DeGraffenreid was both Black and female, she was positioned precisely where those roads overlapped, and was excluded from both the company’s race and gender hiring practices. She was caught in the intersection.

The analytic lenses of the Triangle Model and intersectionality work well together. Using DeGraffenreid’s dilemma as an example, the car manufacturing plant had company/institutional hiring practices that were influenced by the ideas that industrial and maintenance work should be done by men and secretarial or front-office work done by women. The individuals who hired people for industrial and maintenance work had a hiring practice that provided employment opportunities for African-American men, but not African-American women. The individuals who hired people for secretarial or front-office work were influenced by particular ideas of gender and whiteness that impacted their everyday hiring practices such as job interviewing. As explained by anti-racist educator Jodie Glean (2021), whiteness is embedded into employers’ ideas of professionalism which is represented in the ways people speak and dress as well as their knowledge and experience. As well, previous work experience that is valued by employers often mirrors the norm of others in the workplace. For the employers at the car manufacturing plant, white women were seen and heard as being suited and qualified for secretarial work because they spoke and dressed in a particular way and because their previous experience in other white workplaces mirrored the kinds of experience needed for secretarial work at the plant.

Findings: Family Advocacy Work at School

Turning now to an analysis of the kinds of advocacy work LGBTQ, gender unique, and non-binary parents and students take up in Ontario schools, we share what we learned from three different families who participated in the study.[3] The Addley family say they received strong support from their daughter’s first-grade teacher when their daughter transitioned to be recognized as a girl. In contrast, parent Dawn talks about how the school did not respond to any to her daughter’s needs when her daughter transitioned at the age of 8. Finally, Darian and Skye reflect on their own experiences of self-advocacy when they share what happens when high school students don’t have any adults in their lives to advocate on their behalf.

The Addley Family: Transitioning in Grade 1

The Addley family lives in a rural community close to Toronto. They are a family of seven with three parents and four children. All the members of the family identify as white. The Addley’s daughter Violet identifies as trans, while all the other family members identify as cisgender. Ms. Richards, Violet’s teacher, also identifies as white and cisgender. What follows are several excerpts from the Addley family’s interview in 2015 when Violet was seven years old.

SARA (Parent)

We are a family of seven.

MAY (Parent)

Yes. Three parents. We call ourselves polyfidelitous.[4]

SARA

You can google it.

MAY

This is as far as the family, the family goes. No more kids. No more adults. This is the core, this is us. Um, yeah, we uh, I’m at home with the kids. I, uh, volunteer at the school, and I have a little job there as a lunchroom supervisor. So I’m there constantly. And I love it. And uh, try to infiltrate the system with as much positive trans stuff as I possibly can. Fielding a lot of questions for, for Violet …

***

JON (Parent)

… [We decided] we need[ed] a positive experience to put under the transgender cone.

MAY

It was just after she became Violet. So I found out there was the first trans flag raising at [Toronto] City Hall. So I thought you know, this is perfect. So we got all fancied up, and we went down, and we saw the flag go up. And we saw other trans people who were like, encouraging her … They wrapped her in the flag! … And she uh, we arrived at City Hall and she said, “We’re going to a flag raising, because I’m transgender!” And it was the first time she said it out loud! And I’m like, I could feel it coming out, “You don’t have to!” But I didn’t, I was just like “I’m proud of you! You’re so - ” You know! Because it was, it was great, it was just weird for me. So we did that, and uh, you know, we’re leaving and she’s looking back and she’s seeing that flag that represents her, and she’s like, “We should come back tomorrow and see it!”

***

MAY

When it first happened, Violet was like, “Can I just have an assembly and tell everyone?” because she just did not want to ask, or like, answer any more questions.

SARA

That bugged her a lot.

MAY

Questions, questions, questions.

SARA

People asking the same thing every day.

MAY

Every day was just getting more- so I took an active role because they [Jon and Sara] make the money but they encourage me to uh, to volunteer like in her class … and then I’m in all different kinds of classes … as lunchroom supervisor …. So I’m getting the questions. Which is awesome. Because then they don’t ask her ….

***

MAY

… [Y]ou could always tell, uh, she liked all different kinds of things. And [her teacher] Ms. Richards kind of took her under her wing, and, um, every time it was time for her to just start a new class, Ms. Richards would say, “I’m taking her with me. I’m going to the next grade.” And uh, when Violet wanted to wear her Elsa dress for the first time to school, I didn’t have the guts to do it, but I sent it in her bag, and Ms. Richards put it in - put her in it… And she called and said, “She’s in it now, she’s in it now!” And I was like, “Oh my God, what’s happening? Is it okay?” But she was the one to really have, like, the guts. And then I thought from that point on, “Oh my gosh, I need to up my game here ….”

… I would buy dresses but they were pajama dresses …. So you know, I was putting my own kind of labels of what was okay….

… You know, I never anticipated that she would become Violet. I just thought you know, she's a boy who wears pink. But I think upping the game is just questioning ourselves at all these little points that we are blocking her from being herself.

SARA

Not worrying about other people are saying.

MAY

Yes. Because that’s the fear. If you wear a dress and you feel great in front of the mirror, and you feel different leaving, that’s like, that’s not okay. You know, you have to know you felt good in my safe place, and outside is safe too …. [R]ight now, she’s got confidence. And all we gotta do is keep it. Raise it up. (Interview, June 15, 2015)

In her conversation about the kind of advocacy she has engaged in at Violet’s school, May talks about the importance of fielding questions on Violet’s behalf so her daughter doesn’t have to. As a part-time lunch supervisor and volunteer at her children’s school May works hard to respond to the questions students and teachers have about gender and gender transition. As an individual parent she has also worked hard to create relationships with Violet’s schoolmates and teachers so she can challenge oppressive ideas about gender and gender transition. May has been able to “infiltrate the system” and make an impact on the cisnormative[5] institutional practices of the school, by working with the Equity Coordinator and Violet’s teacher to make it safe for Violet to wear a dress, change her name on school records and use the girls’ bathroom.

Turning now to an intersectional analysis of May’s advocacy work, May tells us she has been able to do this work because there are two other family members who bring an income into the family. The family is economically privileged enough for May to work part-time, volunteer in the school, and advocate for Violet. The Addley family’s middle-class status and privilege intersects with May’s identity as a parent of a trans daughter and provides her with the opportunity to advocate for a school environment that allows her daughter Violet “not just survive, but thrive” (Love, 2019, p. 1).

In discussing her own process of becoming comfortable with Violet’s transition, May talks about how Ms. Richards’s individual practice of allyship helped May find the confidence to send Violet to school in a dress. Confidence is key. As May notes, right now Violet has the confidence to be herself. It’s her parents’ job to make sure Violet not only retains, but increases that confidence through their everyday parenting practices.

While Ms. Richards’s individual work was vital in helping Violet socially transition in her classroom, May also received support from a member of their school board’s institutional equity team who helped Violet change her name on her school records. When he began working with the Addley family, the Equity and Inclusive Education Student/Community Facilitator helped the family create an institutional plan for Violet. May recalls, “I remember him asking ‘What do you want? What are you hoping to see for her?’”. This question helped the Addleys imagine their daughter’s future at school. May also credits the individual principal who invited the Equity Facilitator in to support Violet. Having both individual and institutional support from the school allowed the family to change Violet’s names on school records and made her legal transition possible.

Using the Triangle Model to analyze what made Violet’s transition in grade 1 so successful, the team noted that Ms. Richards had the confidence to encourage Violet put on her Elsa dress at school because May and the Equity Facilitator helped her understand the idea that gender is not the same as sex. She learned that while gender refers to a person’s identity and the expression of that identity, sex is a label that refers strictly to a person’s body, especially to the reproductive organs, DNA, chromosomes, and hormone-dependent characteristics like body hair and breast tissue (Reiff Hill & Mays, 2013). Ms. Richards also learned that not everyone’s gender matches their sex (Reiff Hill & Mays, 2013). She understood that Violet identified as a girl even though she was assigned male at birth. The fact Ms. Richards had this knowledge prepared her to work Violet as she transitioned. Ms. Richards used her individual authority as a teacher to make her classroom a safe enough place for Violet to put on her Elsa dress, use the name Violet and use the pronouns she and her. Because of Ms. Richards’s individual support, Violet was able to begin socially transitioning in her classroom. Because there was institutional support from the Board’s Equity Facilitator and a receptive principal, Violet was able to legally transition as well.

Violet is currently in her last year of elementary school and getting ready to graduate into middle school. Both Violet and May stay in contact with the team and make frequent guest appearances in Tara’s graduate teacher education course on gender, sexuality, and schooling. In their talks to new teachers, May and Violet talk about Violet’s experience of transitioning at school and what teachers can do to provide gender unique, non-binary, and trans students with experiences that allow them to thrive at school.

While the Addley family felt well supported by Violet’s principal and Ms. Richards, our interview with parent Dawn reveals that not all children who transition at school have as positive an experience as Violet had, even when their parents do their best to advocate for them at school.

Dawn: When School is Not a Safe Place

City parent Dawn has two daughters. Her older daughter was 10 during our interview in 2016 and identifies as cisgender. Her younger daughter was 8, and identifies as a transgender girl, just like Violet. Dawn doesn’t live with the girls’ father, and she and the girls’ father share custody of their daughters. Dawn and her daughters identify as white.

When Dawn’s younger daughter socially transitioned at the age of 8, she wanted to start fresh at a new school, where people did not know that she had previously presented as male. While the health providers working with Dawn and her daughters also thought switching schools would be a good idea, the girls’ father didn’t want them to. So, the girls stayed at their old school, and made the best of it even though they weren’t happy there. When I asked Dawn to tell us about her daughter’s transition at school, this is what she said.

DAWN

… It’s been pretty difficult. Because it’s been 2 years this month since she sort of started talking a little bit about feeling like a girl. And then it was in April 2015, where she chose out a different name, and has been pretty consistently identifying as a girl. So, [it] was really actually last school year, and part of the school year before where this was in play. And the school, like, I have to say wasn’t super supportive at the beginning. I’ve talked to a lot of other parents in [my city], in [my school board] who had different experiences, but I think because the school had gotten a little caught up with the parents having a conflict, [they] weren’t really thinking about the human rights of the child, and the safe school situation. So last year, not last school year, at the end of the school year before, I contacted the school and asked them if they would bring [a LGBTQ community program] to do education … they bring a trans-identified educator like into the school to educate the staff. And they bring books into the library, and they do different things to make the school a safe space, and then for an individual child, they can also make an accommodation plan for that child. So, I requested that, I didn’t get much of an answer. I requested it again, and I eventually contacted the superintendent.

So, my understanding about that is that if a parent requests it then they have to do it, it’s not really, like, a choice. But it took quite a bit of time, and I think that the school was a little bit like, ‘Mom is saying one thing, Dad is saying something else, so we can’t put accommodation in for the child.’ So then the Program [coordinator] … said, ‘Well, we can come in and do the general education for the school, we’re not gonna talk about which child is identified, even though we all know which child it is.’ So it [had] kind of got around that dad didn’t agree [with his daughter’s decision to transition]. So, they came in and they did the education last year, but still there weren’t really a lot of changes in the actual school itself. They didn’t make a universal washroom which was something that I had requested. And then they also didn’t allow her to use her preferred name. So sometimes she didn’t write any name on her paper. And her teacher would write the name that she was given at birth in pen, last year. So, I feel like she didn’t feel like school was a very safe place …

… So I kinda looked into what the actual rules were, and we made a meeting with the principal before school started this fall. And then my daughter said, ‘I want you to call me by this name at school.’ And the principal was like, ‘What bathroom do you want to use?’ And she was like, ‘I’m gonna use the girls’ bathroom” and the principal was like, ‘What’re you gonna do when the kids say… ‘ And she said, ‘Well, I’m just going to say … and use the new name now.’ So, then the school had no choice. Because when they hear it from the child directly, they can’t say anymore that ‘it’s a conflict between the parents,’ and ‘we can’t make an accommodation without both parents on board’ because of the human rights situation. So, she started the school year with her new name, [and] we had [an accommodation] case conference at the school, I think maybe about 10 days after school started (Interview, November 7, 2016).

Analyzing Dawn’s experience through the Triangle Model, the team noted that unlike Ms. Richards who used her individual authority to support Violet in putting on her Elsa dress, Dawn’s daughter’s teacher used her own authority to prevent her from using her new name in the classroom. When Dawn’s daughter chose to write no name on her assignments rather than write the name she had been given at birth, her teacher would write in her birth name in pen. This practice made Dawn’s daughter feel so unsafe that she wanted to change schools.

To challenge the teacher’s individual authority Dawn researched what the school board’s institutional policies on gender transitioning said about accommodating trans students and accompanied her daughter to a meeting with the school principal. At the meeting Dawn’s daughter clearly stated the name she wanted to be called at school and which bathroom she wanted to use. The school board policy, which is aligned with the 2014 Ontario Human Rights policy on preventing discrimination because of gender identity and gender expression, directs schools to make institutional accommodations for transitioning students who ask for them (for an example of such a policy see Toronto Distrcit School Board, 2013). Because Dawn was able to make use of the institutional authority of the school board’s policy on gender transitioning her daughter started the new school year under her new name and Dawn was able to ask for a case conference to seek other accommodations for her daughter. Researching and using the school board’s institutional policy on gender transitioning to advocate for a transgender child requires a particular set of individual understandings and skills, for example, an understanding of how the policy can be used to legally and socially change a child’s name at school and allowing them to the choice to use whatever bathroom they want to use. Dawn was as a social worker and had acquired these skills as part of her professional social work training. Not all parents who need to advocate for their queer and trans children have access to the middle-class professional education Dawn had access to.

Dawn’s access to middle-class professional education intersects with her identity as a parent of a trans daughter and provided her with the knowledge and skills to use her school board’s policy on gender transitioning to provide her daughter with the support she needed to thrive at school. Importantly, the kind of advocacy Dawn engaged in is not possible for children who attend schools without an institutional school board policy that features protections for gender identity, expression, and transitioning. To address this issue, in October 2019, the Ontario Ministry of Education asked all school boards to update their student conduct codes so that they aligned with the province’s 2014 human rights policy on preventing discrimination because of gender identity and gender expression. Initially not all Ontario school boards complied with Ministry of Education’s directive. For example, several weeks after receiving the directive, a subcommittee of Toronto Catholic District School Board (TCDSB) voted to exclude protections around gender identity and gender expression in its updated code of conduct (Teotonio, 2019). Unlike Ms. Richards, the subcommittee was comprised of individuals who did not accept the ideas that gender can be fluid, and not everyone’s gender matches their sex. Instead, the individuals on the subcommittee replaced the statement of protections with the following statement with an idea they did accept: “all people are created in the image and likeness of God and are deserving of respect and dignity” (Teotonio, 2019).

After a heated debate within the school board, which divided the TCDSB community and circulated hostile and hurtful ideas and comments about the LGBTQ community, the Archdiocese of Toronto (the Catholic Church’s local institution of spiritual leadership in the city) said it would support the board in changing its code of conduct policy to include the terms gender expression, gender identity, family status, and marital status. Following the intervention by the Archdiocese the trustees of the TCDSB voted eight to four in favour of a policy that is “interpreted through the lens of the Catholic faith” as articulated by Church teachings, but that is also in keeping with the ministry directive and the Ontario Human Rights Code (Teotonio, 2019). The amended institutional school board policy now provides a way for individual parents to advocate for their children who want to transition at TCDSB schools.

Since our interview together, Dawn has gained full custody of her children. Her daughters have switched schools, and the principal and teachers at the new school accept her younger daughter as trans. The principal and teachers’ individual support made it a non-issue for the school. Dawn’s younger daughter uses her preferred name and the girls' washroom at school. Overall, Dawn says, school is a much safer place now for both her daughters.

Darian and Skye: Advocating for Themselves

While Violet and Dawn’s younger daughter had the parental support they needed to transition at school, our interview with Darian and Skye provided the team some insight into what happens when queer and trans high school students don’t have any adults in their life to advocate for them.

Darian and Skye met when they were high school students through a mutual friend in 2010. At the time, Darian identified as black and lesbian, but now identifies as trans. Skye has identified as white, cisgender, and queer since high school. Darian and Skye went to different high schools in Toronto. Skye’s high school had a Gay–Straight Alliance (GSA). Darian’s high school didn’t even though the school had a reputation for being “edgy, liberal, [and] progressive” (Interview, March 28, 2018). Skye says having that a GSA at her school gave her comfort. She knew she had “family” in the school even though she didn’t always go to the meetings (Interview, March 28, 2018) Skye’s school had an institutionalized queer-friendly community at school that allowed her to feel safe.

Neither Darian or Skye ended up graduating from the high schools they started at. They both ended up attending two different alternative schools to get the credits they needed to graduate. A week or two before Darian was supposed to graduate from high school, Darian’s mother asked them (Darian uses the pronouns they and them) to leave home because she didn’t like Darian’s “lifestyle” (Darian used air quotes around the word lifestyle when they told this story). Darian ended up living with Skye and her grandparents in a rural town about 3 hours north of Toronto and tried to finish high school there. It took Darian and Skye three years to finish school there because some of the credits they’d earned in Toronto were not valid in the new alternative school they were attending. Both Darian and Skye thought attending the alternative school made sense because they each only needed a few credits to graduate. They also felt that as queer students they would be safer in an alternative school than in a mainstream high school because an alternative school was more likely to have institutionalized a queer-friendly community like the GSA at Skye’s former school.

SKYE

Yeah, we were scared, we were scared. Like we were not, like we’d only ever really, we hadn’t really been out, like um—

DARIAN

For very long really.

SKYE

Yeah.

DARIAN

It was like a year or so. We were still figuring out the ropes, you know, being baby queers! (Laughs) (Interview March 28, 2018)

At first Darian and Skye enjoyed going to the alternative school because there was a large music room (which they felt was a safe institutional school space for LGBTQ students) and the opportunity to play music with the music teacher. However, after spending a good deal of their time in the music room, they realized their music teacher was not teaching them anything they needed to graduate. Outside the music room Darian remembers there were individual kids who were friendly, but who “would use racial slurs and say racist and homophobic things.”

When Tara asked if any of the teachers used their individual authority to stop the slurs, Darian sighed and said, “It’s kind of just how it was, you know? The teachers didn’t really try anything to enforce —”. Before Darian finished their sentence Skye interrupted with the comment, “We didn’t even know how to respond.” Darian agreed adding, “Like it was really hard to stand up for ourselves,” to which Skye added, “We didn’t even have like, the language to do it. And we didn’t, we hadn’t really found our community yet or anything.” Without a teacher using their individual authority to interrupt the racist and homophobic remarks Darian and Skye heard every day at school, without access to the ideas and language they needed to learn to challenge the remarks themselves, and without access to a queer-friendly school community who could support them Skye said, “People were like, walking all over, like all over us.”

The racist and homophobic remarks Darian and Skye experienced in high school demonstrates what going to school can mean for students who identify as white and queer like Skye and queer and Black like Darian. For Skye it meant experiencing homophobic violence and for Darian, it meant experience both homophobic and racist violence. Here our analytic lens of intersectionality allowed the team, and Darian and Skye themselves (see below), to analyze the ways the lack of response to homophobic and racist ideas and remarks in their school perpetuated an institutional culture of heteronormativity, whiteness and white supremacy[6] that made it challenging to survive, and impossible to thrive. Nevertheless, as seen below, Darian and Day persevered, and did not allow themselves to be pushed (Dei et al., 1997; Morris, 2016) out of school. They spent their time as high school students learning new ideas about gender, sexuality, cisheteronormativity,[7] race, and racism online, outside the institution of school. They went to a queer bookstore in Toronto, created their own intersectional queer of color reading list and attended queer of color performance events. They found the activist language, culture, mentors, and teachers they needed within the city’s multiracial, queer community, and began to grow into their “full selves” (Love, 2019, p. 7).

DARIAN

… we didn’t go out much because, you know, we didn’t have a lot of friends and most of the time, it was just, sit in the house and people would be smoking in the room, you know, and it would be too cloudy, you can’t breathe. (Skye nods) You know, it’s a small town! (Laughs) Like, it would be boring after a while so we’d just, you know, stay in our house, you know, sit on Facebook, you know, read all these articles—

SKYE

Yep.

DARIAN

read all these books. (Turns to Skye) We would, we would go, um, with you know, with her Granny or her Grampa to Toronto every time they would go and visit the city because they had to pick something up or whatever so we’d tag along. And you know, we, we’d (turns to Skye) go to some queer things (Skye nods). We’d see like, Catherine Hernandez—

SKYE

Um-hmm. (Nods)

DARIAN

and Kim, Kim Malon. We’d see all these cool queer people and, you know, get all these queer—we’d go to Glad Day [Bookshop]! And get like, ten books and bring them back and just like—

SKYE

Um-hmm.

DARIAN

read a lot … (turns to Skye)

SKYE

Yeah. Yeah for me, it was really about like, finding like, uh, mentors in the community—

DARIAN

Yes!

SKYE

that I could look up to. Like, there was a lot of trans women who I really uh, um, looked up to at the time—

TARA (researcher)

Right.

SKYE

and they were like, activists and they would post a lot about what was going on in the community—

DARIAN

Yeah.

SKYE

and just what was going on, um, like, all over the world. (Looks at Darian) And I felt like that was a really good place to start—

DARIAN

Yeah.

SKYE

I felt like we, I, got a lot of confidence from those people …

DARIAN

… definitely the queer Toronto scene was really good for us when we were living up north (Skye nods) because it just gave us something to look forward to—

SKYE

Um-hmm!

DARIAN

We’d go to like, Crews and Tango’s, just to be surrounded by drag queens—

SKYE

It also just gave us that language—

DARIAN

Yeah.

SKYE

and gave us that education —

DARIAN

Yes, yes.

SKYE

we weren’t receiving or getting anywhere else …

DARIAN

… Definitely, like queer communities definitely made me more aware of my Blackness—

SKYE

Um-hmm.

DARIAN

and the oppression that I was facing.

SKYE

Right.

DARIAN

And all of this, ‘cuz it all intersects—

SKYE

It all intersects, yeah! (Laughs)

DARIAN

It intersects, right? So, it was really—

SKYE

Say it together now! (Everyone laughs)

DARIAN

It all intersects! But yeah, you know, it just, it really made me feel proud to be a queer, trans person-of-color (Skye nods) who, you know, I’ve just never been able to, you know, accept my identity and just feel comfortable in it. And I could see other people doing that. So that just really made me feel good and I really needed that. (Interview, March 28, 2018)

Currently Darian and Skye are living in Toronto and continue to be engaged in the city’s multiracial, queer scene. When our team interviewed them, they were happy and filled with energy and laughter. But it was also clear that they had struggled to finish high school and had no one to intervene in the school system on their behalf. Without adult family to advocate for them at school, their schooling experience was significantly and unnecessarily prolonged and challenging.

Discussion

Reading across the testimonies shared in this piece through the analytic lens of the Triangle Model, we can see that each of the three families responded to the institutional cisheteronormative cultures of their schools by challenging the ideas teachers and principals held about gender and sexuality, and the oppressive everyday practices that were fueled and sustained by these ideas. Parent May Addley made relationships with students and teachers at the school, and answered questions about gender identity, gender expression, and gender transitioning. Dawn used the ideas and authority underlying her school board’s gender transitioning policy to ensure her daughter’s principal would permit her daughter to use her name and use the girls’ bathroom. In addition to surviving the pain of homophobia at school, Darian also had to find a way to survive the pain of white supremacy and look outside their school for new ideas and practices that would help them become a proud queer trans person of color.

The analytic lens of intersectionality helped the team understand how the middle-class economic resources and professional education parents May and Dawn brought to school were key in their ability to advocate for their daughters. May was able to volunteer at the school to answer questions because two other parents were financially supporting their family of seven. Dawn’s training as a social worker gave her the skills to advocate effectively on her daughter’s behalf. Without these kind of family resources, Skye and Darian took longer than necessary to graduate high school and had to pursue the education they needed all by themselves outside of school.

This final discussion point creates a good segue to the implications our findings on LGBTQ family advocacy has for both urban education and teacher education.

Implications for Urban Education

As mentioned earlier, the team interviewed undertaken 37 LGBTQ families living in six different cities in Ontario as well as in the suburbs and rural communities surrounding them. While some of the schools discussed in the interviews have Gay–Straight Alliances, participate in Pink Shirt Day (an annual day to raise awareness about bullying), and have books about LGBTQ families in their classrooms, only one alternative high school, located in the mid-sized city of Oshawa, has created and delivered intersectional LGBTQ-positive classroom curricula.[8] As Toronto parent Victoria Mason reported in her interview, there is a lack of intentionality around the development of the kind of curricula that would allow LGBTQ families to thrive at school.

… We really need to create a space where LGBTQ people and families are normalized. That means that it’s talked about. It’s not that thing that we don’t talk about. It’s part of the curriculum, it's part of the fabric of, of the school, just like the straight families are. You know what I mean? I think there has to be some intentionality. (Interview, February 2, 2015)

The families who participated in our study and attended urban schools identified as Black, Indigenous, Two-Spirit, Filipina, Chicana, and South Asian as well as LGBTQ. Educators in urban schools who struggle for educational justice and believe all students should feel safe at school need to create curricula that features BIPOC LGBTQ families and work towards normalizing their lives at school in whatever ways they can.

Implications for Teacher Education

Knowing that our research team was located in a faculty of education at the University of Toronto, many of the families we interviewed asked us if new teachers were learning anything about gender and sexuality in their teacher education programs. Recently team member Austen Koecher and our colleague Lee Airton published a review of the literature on integrating gender and sexuality diversity in teacher education (Airton & Koecher, 2019). They reviewed 158 English-language sources and concluded that in the 35 years of gender and sexuality diversity teacher education (GSDTE), things have not necessarily “gotten better” (p. 200)—teaching about gender and sexuality in pre-service teacher education remains “a fraught proposition” (p. 200) in many contexts—and that GSDTE “lags behind the always unfolding of gender and sexuality” (p. 200).

Airton and Koecher (2019) also highlight a lack of discussion of transgender parents and students in the GSDTE literature, a lack our research team has tried to address in our research. Importantly, the authors note that “adding trans and stir” to current teacher education discussions on gender and sexuality is not a useful way forward.

Trans lives and narratives are increasingly diversifying away from any exclusive legibility afforded by medical models of transition alone; this may create problems for GSDTE as an intervention in teacher education that has historically privileged stable student-objects and beneficiaries. We may not presently be able to teach teacher candidates what they definitively need to know and do about transness given how transness is changing. More and more young people are coming out as non-binary – not belonging within either binary gender category – or gender-fluid – moving between gender categories – and the articulation of these identities is evolving. This is not to say that transness should not enter the TE curriculum, or that GSDTE can do nothing about transphobia. But … [we need not to] become overly-rigid in how our programs, curricula, policies or structures address or integrate the gender diversity on the transgender spectrum. Overall, it is critical that GSDTE practitioners find ways to hold open a space for however and whoever gender and sexual diversity might be …. (p. 200)

One of the strengths of our video interview study with LGBTQ families, we believe, is that the 300+ video clips we have curated and uploaded onto on our website provide a place for families share how their individual experiences of gender and sexuality have shaped their experiences at school. When the team shares the wide variety of their experiences with new teachers, we are able to hold open a space for “however and whoever” gender and sexual diversity is in the families attending school and think about the ways we might prepare teachers for gender and sexualities that are not yet imaginable.

We invite educators everywhere, in urban, suburban, and rural schools, to spend some time with the families we interviewed, listen to their testimonies, and begin thinking about the ways they can support families in their own schools who have similar stories to share.

[1] The research team uses the initialism LGBTQ (lesbian, bisexual, gay, transgender, and queer) to talk about our research with the intention of including people who identify as transgender, transsexual, two-spirit, questioning, intersex, asexual, ally, pansexual, agender, gender queer, gender variant, and/or pangender. However, we understand the names people use to describe their gender and sexual identities are always evolving and that the most important thing is to be respectful and to use names that people prefer.

[2] The research study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRCC) between 2016 and 2020 through an Insight Grant.

[3] The team provided all participants with the opportunity to use a pseudonym when excerpts of their interviews were uploaded onto our website. All names of participants herein are pseudonyms.

[4] Although Parent Sara Addley encourages people who don’t know what the term polyfidelitous means to google it for themselves, we define it as describing an intimate relationship structure where all members are considered equal partners in a secure relationship and agree to maintain relational intimacy solely with other members of this group (hicks & Goldstein, 2021).

[5] To understand the meaning of the phrase “cisnormative institutional practices at school” it is helpful to begin with the terms transgender, cisgender, cissexism and cisnormativity. A transgender person is someone whose sense of their own gender identity differs from the biological sex that they were assigned at birth (hicks & Goldstein, 2021). The prefix trans- in the word transgender is a Latin prefix meaning “the other side of”, cis- means “the same side of” (hicks & Goldstein, 2021). A cisgender person is someone whose gender identity and expression match the social expectations for the physical/biological sex they were assigned at birth based on a binary, medical perception of their sex chromosomes, gonads, reproductive chromosomes, and external genitalia. Cissexism is the assumption that all people will identify with the gender that corresponds to the sex that they were assigned at birth and that a cis person’s gender identity is more authentic, “real”, natural or desirable than a trans/GD person’s gender identity (hicks & Goldstein, 2021). Cisnormativity is the assumption that all, or almost all, individuals are cisgender. Cisnormative institutional practices at school refer to practices that stem from the assumption all, or almost all, individuals at school are cisgender.

[6] Heteronormativity is the assumption that all, or almost all, individuals are heterosexual. A heteronormative school culture is a school that perpetuates the assumption all, or almost all, individuals at school are heterosexual. A school culture of whiteness perpetuates the assumption the individuals at school are all, or almost all, white. A white supremacy school culture perpetuates the assumption that the ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions of white people are superior to those of people who identify as BIPOC. White supremacy can express itself interpersonally as well as institutionally.

[7] Cisheteronormativity is the assumption that all, or almost all, individuals are cisgender and heterosexual.

[8] To learn more about this school’s queer curriculum see Letter 22, Expecting LGBTQ Families and Studies at School in Goldstein (2019).

Airton, L., & Koecher, A. (2019). How to hit a moving target: 35 years of gender and sexual diversity in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 190–204.

Assembly of Catholic Bishops of Ontario. (2010, October 4). A statement from the Catholic Bishops on policy development associated with Ontario’s equity and inclusive education strategy [Press release]. https://www.tcdsb.org/Board/EIE/Documents/Statement%20-%20Equity%20%20Inclusivity%20in%20Education%20Oct%204%202010.pdf

Boluda, A. (Director & Producer). (2005). Queer Spawn [Film]. Anna Boluda Productions. https://www.cultureunplugged.com/documentary/watch-online/festival/play/3206/Queer-Spawn

Brill, S., & Pepper, R. (2008). The transgender child: A handbook for families and professionals. Cleis Press.

Callaghan, T. D. (2007). That’s so gay: Homophobia in Canadian Catholic schools. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

Casper, V., & Schultz, S. (1999). Gay parents/straight schools: Building communication and trust. Teacher’s College Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and anti-racist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139–168.

Crenshaw, K. (2016, October). The urgency of intersectionality [Video]. TEDWomen 2016. https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality

Crosby, A., & Lykes, M. B. (2019). Beyond repair?: Mayan women’s protagonism in the aftermath of genocidal harm. Rutgers University Press.

Dei, G. J. S., Mazzuca, J., McIssac, E., & Zine, J. (1997). Reconstructing 'dropout': A critical ethnography of the dynamics of black students' disengagement from school. University of Toronto Press.

Episcopal Commission for Doctrine. (2011). Pastoral ministry to young people with same-sex attraction. Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. https://truthandlove.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ministry-ssa_en.pdf

Epstein, R. (Ed.). (2009). Who’s your daddy and other writings on queer parenting. Sumach Press.

Epstein, R., Idems, B., & Schwartz, A. (2013). Queer spawn on school. Confero: Essays on Education, Philosophy & Politics, 1(2), 173–208.

Glean, J. (2021, February 10). Understanding everyday whiteness: Anti-racism training module 2. Anti-Racism and Cultural Diversity Office, University of Toronto.

Goldstein, T. (2005). Performed ethnography for anti-homophobia teacher education: Linking research to teaching. Canadian On-Line Journal of Queer Studies in Education, 1(1). http://jqstudies.oise.utoronto.ca/journal/viewissue.php?id=3

Goldstein, T. (2010). Snakes and ladders: A performed ethnography. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(1), 68–113.

Goldstein, T. (2014). Learning from other people’s families. Teaching Education, 25(1), 65–81.

Goldstein, T. (2019). Teaching gender and sexuality at school: Letters to teachers. Routledge.

Goldstein, T. (Ed.) (2021a). Our children are your students: LGBTQ families speak out. Myers Education Press.

Goldstein, T. (2021b, March 15). The experiences of LGBTQ families in Ontario schools [Final Report]. http://www.lgbtqfamiliesspeakout.ca/publications.html

Goldstein, T., Baer, P., & Salisbury, J. (2021). This is our family: A verbatim theatre script. In T. Goldstein (Ed.), Our children are your students: LGBTQ families speak out (pp. 41–103). Myers Education Press.

Goldstein. T., Koecher, A., Baer, P., & hicks, b. l. (2018). Transitioning in elementary school: Advocacy and allyship. Teaching Education, 29(2), 165–177.

hicks, b. l. (2017). Gracefully unexpected, deeply present, and positively disruptive: Love and queerness in classroom community. In D. Linville (Ed.), Queering education: Pedagogy, curriculum, policy (pp. 130–144). Bank Street.

hicks, b. l. & Goldstein, T. (2021). Naming and renaming. In T. Goldstein (Ed.), Our children are your students: LGBTQ families speak out (pp. 168–183). Myers Education Press.

Hollins, E., & Guzman, M. T. (2005). Research on preparing teachers for diverse populations. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 477–548). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Houston, A. (2012, June 14). Mission accomplished. Xtra!: Toronto’s Gay & Lesbian News, 721, 14–17.

McCaskell, T. (2005). Race to equity: Disrupting educational inequality. Between the Lines.

McNeilly, K. (2012). Beyond the ‘bedrooms of the nation’: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of Canadian adolescents with lesbian, gay, or bisexual-identified parents [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Toronto.

Morris, M. W. (2016). Pushout: The criminalization of Black girls in schools. The New Press.

Reiff Hill, M., & Mays, J. (2013). The gender book. Marshall House Press.

Robinson, K. H. (2005). Doing anti-homophobia and anti-heterosexism in early childhood education: Moving beyond the immobilizing impacts on ‘risks’, ‘fears’ and ‘silences’. Can we afford not to? Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood Education, 6(2), 175–188.

Robinson, K. H., & Ferfolja, T. (2001). “What are we doing this for?” Dealing with lesbian and gay issues in teacher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 22(1), 121–133.

Robinson, K. H., & Ferfolja, T. (2002). A reflection of resistance: Discourses of heterosexism and homophobia in teacher training classrooms. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 14(2), 55–65.

Snell, P. (2013). Video, art, and dialogue: Using the internet to create individual and social change. The International Journal of Communication and Linguistic Studies, 10(1), 27–38.

Taylor, C., & Peter, T. (2011). Every class in every school: The first national climate survey on homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia in Canadian schools (with T. L. McMinn, T. Elliott, S. Beldom, A. Ferry, Z. Gross, S. Paquin, & K. Schachter) [Final Report]. Egale Canada Human Rights Trust.

Taylor, K.-Y. (Ed.). (2017). How we get free: Black feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Haymarket Books.

Teotonio, I. (2019, November 9). Catholic board to amend its code on gender issues. Toronto Star, A7.

Thomas, B. (1987). Multiculturalism at work: A guide to organizational change. YWCA of Metropolitan Toronto.

Toronto District School Board. (2013). Guidelines for the accommodation of transgender and gender non-conforming students and staff. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/AboutUs/Innovation/docs/tdsb%20transgender%20accommodation%20FINAL_1_.pdf

Waring, A. (2013). Confessions of a fairy’s daughter: Growing up with a gay dad. Alfred A. Knopf.