Libro + Biblioteca = Libertad

On the margins of El Paso, Texas, a teacher-librarian communicates daily to her students the following bilingual mantra: “Esta biblioteca les pertenece a ustedes. This is your very own library.” Lisa M. López-Williamson is the teacher-librarian and literacy activist and advocate at William “Guillermo” C. Herrera Elementary School in the El Paso Independent School District. She is a celebrated teacher-librarian who cares about family literacy. Proudly bilingual, she works to advance the intellect, creativity, and imagination of children through digital and print literacies that foster social responsibility. She identifies herself as a young Latina of Mexican descent and borderlands citizen who can directly influence young people’s bilingualism, biculturalism, and biliteracies.

The library serves a school population of nearly 500 students, 96 percent of Hispanic origin. Lisa explained that her school building houses three libraries in one to increase bilingual readership among students—during all hours and every day of the year. In addition to the main school library that is open during the academic year and part of the summer, there is one Little Free Library outside, and another indoors. A Little Free Library is part of a larger non-profit network of free book exchanges with the motto “Take a Book, Return a Book.” The libraries vary by shape and size, although the most common version is a small wooden box with glass doors that open to house books for readers. Anyone takes a book or brings a book to share. The outdoor Little Free Library is open year-round for readers and families. Although situated along the largest border and enforcement zones of North America, these three school libraries are free of borders and limitations.

In some public schooling communities, high-stakes testing and corporate-style schooling have led to the closing of school-based libraries. Some school librarians are forced to reduce or, even worse, remove programming that allows students, teachers, and parents to experience the joy of reading and literacy, free from assessment and evaluation. In response to a similar context found in “Reimagining Reading: Creating a Classroom Culture that Embraces Independent Choice Reading” (2015), Dickerson argues, “If we are to educate for character and growth and success, we need to stop seeing our students as a standardized other, one on which we need to impose a certain kind of knowledge” (p. 8). Lisa noticed that public and private resources for libraries dwindled across El Paso, reducing access and readership. Lisa wanted to keep libraries open with longer hours of operation for young people and their families. Instead of stifling her students’ creativity or succumbing to the isolation that can happen within schools, Lisa rolled up her sleeves and found ways to engage citizens to deliver books and stories for all.

Figure 1. Lisa prepares for a bilingual lesson with a picture book and manipulatives.

Much of Lisa’s work mirrors what Ofelia García (2009) emphasizes: “Bilingual education in the twenty-first century must be reimagined and expanded, as it takes its rightful place as a meaningful way to educate all children and language learners in the world today” (p. 9). In early Spring 2014, Lisa welcomed me to her school library as a volunteer and university-based researcher while I was writing classroom and library curriculum on English and Spanish language arts. The observations and interviews occurred over a three-month period with my visiting during her planning period, observing one pre-approved class, staying for an after-school library book borrowing session, and communicating via email and telephone to clarify observations, interpretations, and instructional decision-making. She and I maintained contact through the 2015-2016 academic year and engaged in a book exchange in my role as a literacy researcher. Overall, the interview method was favored in support of what Sonia Nieto (2013) calls an “effective, close-up way of gaining a personal perspective” for teachers to “reflect on their philosophy and practice” and their “chance to talk about what’s important to them and why” (p. xv).

Upon moving to El Paso in August 2013, I read an article in Library Journal that featured Lisa as a celebrated school librarian and a 2013 Movers & Shakers honoree. I decided to reach out to her in my literacy research and to document her efforts and approaches to diverse literacies in the Chihuahuan Desert borderlands. After gaining access and authorization, my purpose was to observe and document the bilingual, bicultural, and biliterate practices and resources in action. The following sections summarize my interview with Ms. López-Williamson.

Promoting Community Literacy: A Cultural Context

Even before I enter the school, the outdoor Little Free Library is alive with movement and conversation between students and their parents. A book talk is occurring en vivo, in real life. The Little Free Library consists of a wooden box full of donated and exchanged books. The library circulates on the honor code regardless of the book borrower’s zip code and income level.

Figure 2. The Little Free Library welcomes patrons and prospective readers of all ages.

Families and neighbors gather around the books to share their favorite stories in Spanish and English. On this Spring morning, I witness a mother and a daughter sharing a book exchange at the Little Free Library. “¿Cuál libro quieres, mi’ja? Dime,” “Which book do you want, my daughter? Tell me,” a mother asks in the entrance area to the school. Tell me the book you’d like, she asks. Her daughter answers, “El de dinosaurios, Mami.” “The one about dinosaurs, Mommy.” She’d like to read about dinosaurs of the class Dinosauria. In this book she’ll read about the Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis in one of these three libraries located at the Texas-México border. Dinosaurs, like books and borrowers, are diverse specimens.

Writer Judith Ortíz Cofer’s (2010) observation about libraries is confirmed at the Herrera Elementary School grounds. Ortiz Cofer explains, “A library is my sanctuary, and I am always at home in one” (p. 133).

For the interview, I drafted the questions after the initial observations. This was deliberately done beforehand to dig deeper into the interactions among borrowers and the librarian. Most of my research was informed by Gloria Ladson-Billings (1994, 2009) perspective of “community nomination” and to advance culturally relevant teaching and literacies. The questions were open-ended with the purpose of seeking the librarian’s own agency and identification, which involves decision-making about selecting books, honoring students’ ethnic cultures and home languages, and maintaining mindfulness about civic responsibilities.

R. Joseph Rodríguez (RJR): One of your libraries is a Little Free Library located in the front schoolyard. It’s open 24-hours a day, year-round, and free from locks, fences, and patrols. How did you bring the vision and goals for the Little Free Library to greater El Paso?

Lisa M. López-Williamson (LML-W): All of this began in Fall 2010. I had just earned my master’s degree in library sciences, and I was reading positive, inspirational stories on the website DailyGood: News That Inspires. One was about a small birdhouse that became a mini-library. After reading about this, I went to Michael’s. I found a small box that would become the beginning of the Little Free Library Movement in our borderlands communities.

Figure 3. A welcoming space with seating and a Little Free Library are always a treat.

The school’s fourth graders helped me decorate the box with primary colors, and we added paperback books and Reading Is Fundamental titles. We filled up our very own Little Free Library with age-appropriate books for borrowers at our school.

Each Little Free Library is unique with its own character and affiliation. I shared the history about it with the students and informed them this was a global movement from China to the USA and which began in Madison, Wisconsin.

Figure 4. Lisa makes books come to life before her students’ eyes and for a biliterate life.

Growing Up in the Borderlands

RJR: Tell me about your growing up in the borderlands.

LML-W: I was born in El Paso and educated in a bilingual school across the Río Bravo in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, México. Most of my schooling was Spanish-language dominant with some instruction in English. It was through television that English came to life.

RJR: Tell me how you became interested in books.

LML-W: There were librerías, or bookstores, that my family frequented in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Bookstores are prominent in México. However, there just weren’t any public libraries as we know them in the United States or libraries in the public and private school campuses. The only option that existed was to buy books for reading.

RJR: When did the shift occur from the bookstore to the public library experience?

LML-W: When I became a teenager, we moved to El Paso. I returned to El Paso and began 7th grade at a neighborhood middle school. I was placed in classes for English for Speakers of Other Languages. By 8th grade, I was placed in English immersion classes.

Even as a teenager I wanted my library card right away. My parents took us to the Westside Branch of the El Paso Public Library. I remember borrowing up to 15 books at a time. It was a tall stack of books I carried in my arms. I read as much as I could. As I read and re-read books, I imagined other worlds.

RJR: Tell me about your schooling.

LML-W: My sister and I experienced culture shock trying to fit in at school in El Paso. From the adults, we faced limited expectations toward early marriage and starting a family. This was discouraging to experience in a public school. I wanted another learning environment that had higher expectations and regard for me as a human being and female with choices for her consideration and choosing. As a result, my junior year of high school I dropped out. My mother was supportive and encouraging, because it meant continuing my studies in a place that would value my intellect, abilities, and convictions as a young person.

RJR: And then what happened?

LML-W: The same day I dropped out in 1997, I signed up for the GED at El Paso Community College. I passed, and the rest that followed was like making my own history and story. It was a time of transition for me, and I began to take college classes I really liked and connected with me.

Later in 1999, I transferred to The University of Texas at El Paso. It was a children’s literature course that changed my course in life. I learned about early literacy development, book selection, and annual awards. A class project required students to visit public libraries and write about we observed in action. I liked what I saw and imagined a bilingual world for readers and thinkers of all ages and colors.

Bookjoys!

RJR: What’s creating all the bookjoy, excitement, and enthusiasm that keep your students coming back for more, Lisa?

LML-W: The children have access to more than 14,500 books in English and Spanish with a growing collection in Spanish. They have their favorite authors and books, and they get to lead book talks that we have in the library. Some we record digitally to share students’ reading interests and habits across the grade levels.

Interestingly enough, the students in the upper-grades influence the younger readers by recommending their favorite books. It’s convincing when they present themselves as book critics and even with spoiler alerts. Students learn best from each other and when they get to share what they’re learning with a peer audience that’s supportive. We all get excited and have fun and laugh.

RJR: How do you bring oral traditions and storytelling into your teaching?

LML-W: I’ve used the oral tradition as a good launch with students. Our students know many stories and they get to enact them through storytelling and puppetry.

The students become storytellers and practice literacies through plays. For example, the story of Hansel and Gretel is appealing to them, especially the style of the cautionary tale that appears in Latin American storytelling. I was pleased to experience that students knew the story plots to tell stories. We all learned about their familiarity with storytelling and their interests in the performing arts.

Figure 5. Seats are always available to the next bilingual reader in formation.

RJR: How are you connected to the larger school community?

LML-W: The library is the heart of the school and community; I believe this. Also, the beginning of the school year is a perfect time to engage teachers during professional development week and throughout the school year. I take the initiative, and I am active in their classroom. I drop in, take notes, and seek collaboration. I am involved.

I keep the library open to everyone, and I make sure to stay active with teachers and organizations such as the PTA and Girl Scouts of the Desert Southwest, which are inviting and collaborative in their programming. There are also parent volunteers who care about our school library. We depend on them and their presence, which influences how we view libraries and the power and pleasure of a child’s reading life beside the adults who care about them.

RJR: What recommendations do you have for other teachers?

LML-W: Students need to be able to talk about what they’re reading or interested in reading. We can begin and maintain a conversation that involves their interests and curiosities. Moreover, teachers can support the students by allowing book selection and giving them opportunities to talk about their experiences as readers in Spanish and English.

Dual Languages and Learning in the Library

To support the dual language curriculum in the library, Lisa communicates and collaborates with the school’s subject-area elementary teachers to agree on the language of instruction and books for borrowing that will inform and enrich the library period. This ensures that two languages are held in equal esteem and value, as well as celebrated across the elements of literacy and learning. On occasion, however, Lisa begins a picture book, nonfiction, or novella oral reading with a key question:

“¿Prefieren que les lea este cuento en español o inglés?” Would you prefer this story told in Spanish or English?

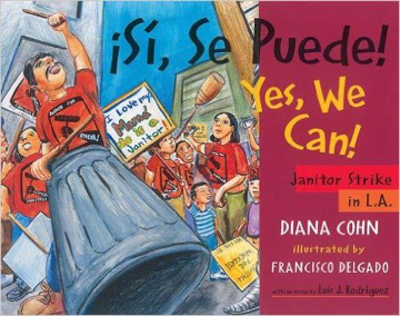

“En español. In English. Los dos idiomas,” they respond in a jumbled chorus that roars across the open library. Both languages are preferred and supported here. “Vamos a votar. Let’s go ahead and vote,” Lisa suggests. Democracy is enacted with equal participation and voice among the youngest learners. There’s buy-in and participation among our youngest citizens. Spanish wins on this round, yet students follow up after the storytelling with a request for the English-language version. Lisa launches the storytelling in rhythmic, vibrant sounds and makes the story unfold through a series of bilingual books that include authentic, everyday situations faced by characters in works such as ¡Sí, Se Puede!/Yes, We Can!: Janitor Strike in L.A. (2005), which was written by Diana Cohn and illustrated by Francisco Delgado. With picture books carefully studied and adapted for instruction, Lisa searches for stories that connect with her students’ diverse backgrounds, realities, and interests that include their working-class backgrounds and cultural and linguistic wealth. She begins and shares the true story about the hard-working janitors who united for fair working conditions in Los Angeles in 2000. The picture book is accompanied by the voices of a working mother and her school-age son:

—Que sueñes con los angelitos, Carlitos,—dice mamá cuando me tapa con las cobijas.

—Hasta mañana—le digo y cierro los ojos.

Mientras todo el mundo duerme, mi mamá va al trabajo. El autobús la lleva al centro de Los Ángeles donde los rascacielos se alzan de las ac-eras. Por la noche, todas las calles están vacías.“Sleep with the angels, Carlitos,” says Mamá when she tucks me in.

“See you in the morning,” I say and close my eyes.

While everyone sleeps, my mamá goes to work. She rides the bus into downtown Los Angeles where skyscrapers shoot up from the sidewalks. At night, the streets are empty. (p. 2)

The students connect with Carlitos and the worlds he inhabits as a student, young person, and son as his mother works tirelessly to make ends meet, but also expresses her love and devotion to him. They want the story performed again by Lisa, and she insists they reflect on what work means for adults—day and night—and how people work together to problem solve and create change that’s necessary. The students want to know if, by chance, she’s the teacher named Miss López in the book.

Figure 6. The picture book is popular for book borrowers.

Languages with Opportunity for All and Libertad

RJR: How is language important in your teaching, Lisa?

LML-W: As a bilingual librarian, I realize the value of language learning. In my experience, the sense of shame in one’s roots and tongue can appear. For instance, the language spoken at home is often Spanish and at school, if there’s an English-only environment, this does not help our students. There must be maintenance of both languages without interruption, punishment, and penalty. We must encourage the use of our mother tongue. A dual language curriculum, however, involves students learning from one another and also having a teaching role to support their peers.

RJR: How do you make space for both Spanish and English in your library?

LML-W: The development of the library collection and use of Spanish-language materials are a big priority at my school. Although vendors can affect selection with limited titles, I have the advantage of a local publisher committed to dual language titles with a culturally responsive interest. I am aware that I must select books that mirror the Spanish and English spoken in our students’ homes and our region.

RJR: Although English can dominate in the broader society with the tendency of English to dominate when languages are side by side, describe how you create space for Spanish in your library.

LML-W: Our school has full, dual language education across the grade levels. The teachers and I communicate regularly on the language under study for library visits and to advance the dual language curriculum. As a result, I serve as librarian, interpreter, and translator of picture books and storytelling to reach children of diverse linguistic backgrounds and interests. Mainly, I understand my role as I observe students transfer skills from one language to another to make meaning on their own and with their classmates.

RJR: Tell me how you promote the use of Spanish as a world language.

LML-W: Both languages are of equal value for learning, and students pick up on how we honor the world languages they speak, what we value in any language as adults, and what we welcome for learning. I make sure that equal time is dedicated to both languages, or the particular world language of study, during the library visit. I create learning opportunities with digital and print books for listening, performing, questioning, reading, speaking, thinking, viewing, and writing across the subjects.

A recent gift our library received during National Hispanic Heritage Month was from the Morgan Stanley Foundation. We hosted a Spanish-language book giveaway to support home libraries, bilingual communication, and biliteracy practices in the lives of children and their families.

RJR: How do you make sure your library has enough Spanish language resources?

LML-W: I am always searching for more materials and speakers to make connections across English and Spanish. We must have models of how language works to make meaning, transfer ideas, and introduce concepts through biliteracy. To illustrate, the author and storyteller Joe Hayes came to our school in December 2014. He modeled dual language in action through his digital and print books. As a reader, author, and communicator, Hayes is fluent in Spanish and English. He enacted these skills before our students and displayed the advantages of global learning to communicate with people of diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, including Mexican and Latino-origin families.

RJR: Tell us how to support bilingual teachers, students, and families.

LML-W: I realize I am a member of communities that value Little Free Libraries, dual language education, and children’s imagination in the borderlands. I believe this can happen across the country and diverse spaces in education. What we are doing in Texas, New Mexico, and the Mexican state of Chihuahua is replicable.

My community engagement as a volunteer with the Little Free Libraries Movement is to create more connections and collaborations to value world languages and literacies. We must make books accessible, especially where libraries closed their doors or are nonexistent for miles in residential areas. Books and languages matter in our homes, schools, and community libraries. By the end of 2015, there will be more Little Free Library installations than McDonald’s restaurants around the globe. There is power and energy in this literacy movement for accessible libraries and dual languages.

RJR: How can we increase the movement for language learning and instruction that begins with bilingualism and biliteracies?

LML-W: Language is an asset that can bring academic and social strengths for all students, teachers, families, and communities. Many benefit when we value language as well as the human imagination, knowledge, and cultures that influence it. Students know what we value and that must always be strength-based about their homes, languages, cultures, and literacies that are promising with opportunities to thrive in and out of school.

Language is never a barrier. In fact, language is a window with infinite opportunities. We must begin to value the experiences and perspectives of the children and families we serve at much higher levels. We can work together to make learning happen by welcoming young people’s imagination and by believing in their language transfer and problem-solving abilities.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge Lisa M. López-Williamson for her commitment to a life of bookjoy and literacy wonderment for children, young adults, and adults in the greater U.S. Southwest borderlands. A special thank you is extended to the Little Free Library team in Hudson, Wisconsin, and the stewards across the planet for promoting and supporting the motto: “Take a Book, Return a Book.” Share more bookjoys!

Cohn, D., & Delgado, F. (2005). ¡Sí, se puede! / Yes, we can!: Janitor strike in L.A. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos Press.

Dickerson, K. (2015). Reimagining reading: Creating a classroom culture that embraces independent choice reading. Perspectives on Urban Education, 12(1). Retrieved from http://www.urbanedjournal.org/archive/volume-12-issue-1-spring-2015/reimagining-reading-creating-classroom-culture-embraces-indepe

García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Nieto, S. (2013). Finding joy in teaching students of diverse backgrounds: Culturally responsive and socially just practices in U.S. classrooms. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Ortíz Cofer, J. (2010). The Paterson Public Library. In The Latin deli: Telling the lives of barrio women (pp. 130-134). Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.