Reimagining Reading: Creating a Classroom Culture that Embraces Independent Choice Reading

Many of us are plagued by negative memories of sustained silent reading. In some of these memories, we are the students, attempting to read a book that didn’t hold our interest or trying to read over the din of our disengaged classmates. In other memories, we are the teachers, suffering through a ten-minute classroom management nightmare, deciding which pupil behaviors to ignore and which to address.

In my own classroom, when I use the term SSR—the acronym for sustained silent reading—I sometimes get visceral reactions from even my best students. Most likely, they have had similarly scarring experiences with SSR before they reached my American Literature class. My students come to our school from many different places: other North Philadelphia middle and high schools; schools in Central America, the Caribbean, or Africa; or various schools throughout the United States. The North Philadelphia community in which we are located is a transient one, partially because of the poverty of its members and the way that affects the stability of housing, and partially because of its large immigrant population.

Introduction

I can certainly see the challenges this community faces when I look at our school. These challenges are evident, for example, in statistics on our student population: roughly 22% of students receive special education services, 25% are English language learners, and 83% are from families whose income is below the poverty line. Though I do not have statistics to back up this observation, I have noted that a handful of my students have parents who are unable to read. Additionally, out of the 60 students in my 2014-15 class, just two have at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree (L. Rosario, personal communication, Nov. 2, 2014).

My students’ educational backgrounds, especially in terms of literacy, starkly contrast with my own experience in school, and this has impacted my teaching practices on a fundamental level. Most importantly, many of my students do not initially enjoy reading, whether independently or as a class. For this reason, I have consistently tried to make reading both entertaining and relevant. Since I started teaching in 2010, I have developed a toolbox of student investment builders: incorporating short stories and novels that are culturally relevant to my students, including activities like “Doubters and Believers” [4] that build student interest before and during reading, using group work and acting to analyze texts and bring them to life, and assigning creative responses to literature in addition to more academic essays.

Long before I became a teacher, I was a reader. Bedtime stories were a routine in my youngest years, and both of my parents frequently read for pleasure. My family visited the public library. Because of that, I began reading novels toward the end of elementary school. As a young adult, I volunteered with a teen program at our local library. I have always been an avid reader, and there is very little in the world that is more important to me than books.

Returning to that original love of reading for pleasure has helped me grow immensely as a teacher. In my own more recent schooling, I have taken up reading as an area of study; specifically, I’ve grown interested in the impact of reading narrative (either fiction or creative non-fiction) on at-risk youth. Through a series of interviews, I found that reading is actually linked to a number of protective factors that contribute to resilience: the establishment of future goals, an internal locus of control, optimism, a sense that one’s problems are trivial, open-mindedness, the need to take responsibility, the ability to empathize with others, strong communication skills, and the ability to focus. Aren’t these characteristics that every teacher wants his or her students to possess?

Methodology

For these reasons, I have been on a two-year journey to incorporate more independent reading and more choice reading into my classroom. Over the years, I have collected data in a variety of ways. For the sake of simplicity, I will talk about this data chronologically.

Within the first two months of the 2013-2014 school year, I took a purposeful sampling (six students in each class, or about twenty percent of the class) of students in each of my 11th grade classes and tested their reading levels using the San Diego Quick Assessment. I aimed to test two students who performed well in my class and appeared to read with ease, two students who struggled in my class and had an aversion to reading, and two students in between. The population I sampled ranged in independent reading level from fourth grade to eleventh grade, with an average reading level of seventh grade for my non-honors class and ninth grade for my honors class. I used this information to help find suitable books for my classroom library.

Students read independently during Reading Zone, a time at the start of class dedicated to independent choice reading. They can choose books from my class library or bring a novel from home. For the 2013-2014 school year, my students had ten minutes of Reading Zone every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. I read with them. I told them about my books. Reading Zone was a sacred time—not time for the bathroom or for doing last night’s homework—and though we read silently for a sustained period of time, it helped to manipulate the wording I used when talking about reading with the students.

As they read, they tracked their progress (date, minutes read, and number of pages read) with reading trackers. For each book that they finished, students were given the opportunity to write an extra credit paper about something they learned from their book; this was not mandatory, however, and though I gathered some data in this manner, many students chose not to do this, and so that data is limited.

During the current 2014-15 school year, I teach fifty-eight students, two classes of honors English. Despite being placed in an honors class, not all of the students read on grade level or have good grades, but some of them do. A little more than a third of them considered themselves to be “regular readers,” and only three said they read every day. For this group of students, I increased Reading Zone time to between ten and twelve minutes a day. I also put into effect five rules (which I will expound upon later): a book is a book; I read, too; we talk about our books; we write about our books; we are free to ditch our books. These five rules gave students more choice and autonomy while also presenting reading as a community activity.

In addition, I changed the way I collect data with this group of students: it is mainly through the implementation of readers’ notebooks. These notebooks serve a variety of integral functions in my classroom. On the inner cover is a reading tracker where students list the titles of books they’ve completed, the date completed, the genre, and a rating between one and five stars. The notebooks also contain a list of thinking stems (i.e., sentence starters) organized by level of difficulty in a chart similar to Bloom’s Taxonomy. The students can choose to use these thinking stems to start their journal entries, of which I require three a week. These entries should be about the book a student is currently reading. I encourage students to choose more challenging thinking stems to produce deeper, more complex ideas in order to grow both as readers and as people, and they often do.

In addition to our readers’ notebooks, we track the genre of the books we read on large, colorful trackers in the back of the room. When a student finishes a book, he or she can add a sticker to the tracker. Above the trackers is a running list of all the books my students have read, which includes the names of the books and of the students who read them. This allows students to go to one another for book recommendations.

Other than these systems, there are other, smaller ways that I am gathering data in the 2014-2015 school year. I give a reading survey at the end of each quarter that is very similar to the survey I administered at the end of last school year: It asks students’ opinions, number and kinds of books they have read, and so on. I also gather a good deal of my data anecdotally from conversations I have with students about the books we are reading. Each kind of data—quantitative and qualitative—informs me about different aspects of independent choice reading in my classroom.

Results

Increased Reading Levels

At the end of the 2013-2014 school year, I retested the reading levels of students in the sample group with the exception of two, one of whom transferred and another who dropped out. Students showed varying levels of improvement, an increase of between one and three grades levels. However, this cannot be linked directly to independent reading in Reading Zone since the students read a variety of other texts both in my class and in other classes. I also administered an anonymous Reading Zone Survey at the end of the school year. This survey (See Appendix A) had both factual questions (regarding the quantity and quality of books read) and opinion questions (focused on their feelings and attitudes toward reading, Reading Zone, and themselves as readers).

Moderate Engagement

The first small hurdle for me came with the language I used to talk about reading. Labels are loaded with connotations, and naming is incredibly important. Though I briefly contemplated using the term SSR, I decided the students would be less reluctant to accept the term Reading Zone. Though students were practicing sustained silent reading, it helped to manipulate the wording I used to talk about this practice.

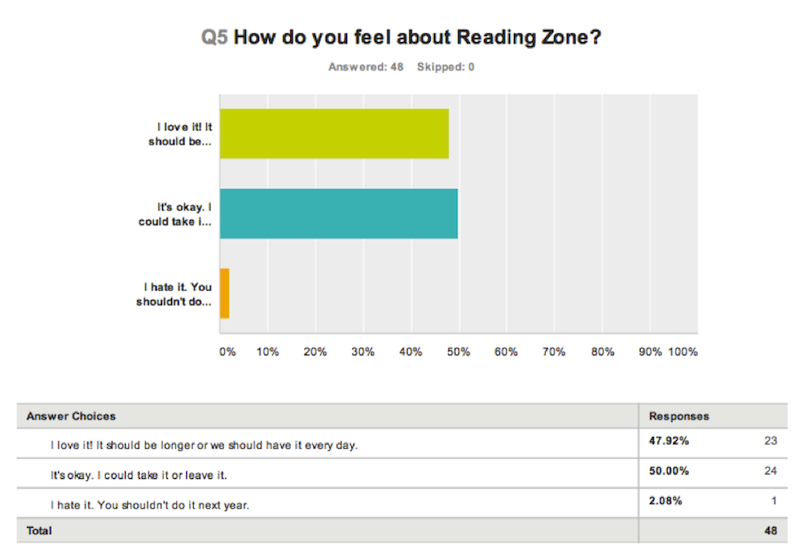

This approach achieved moderate success, as I determined from an end-of-the-year survey in June 2014. For example, when asked about Reading Zone changes for the 2014-2015 school year, 47.9% of students said I should implement it every day (see Figure 1).

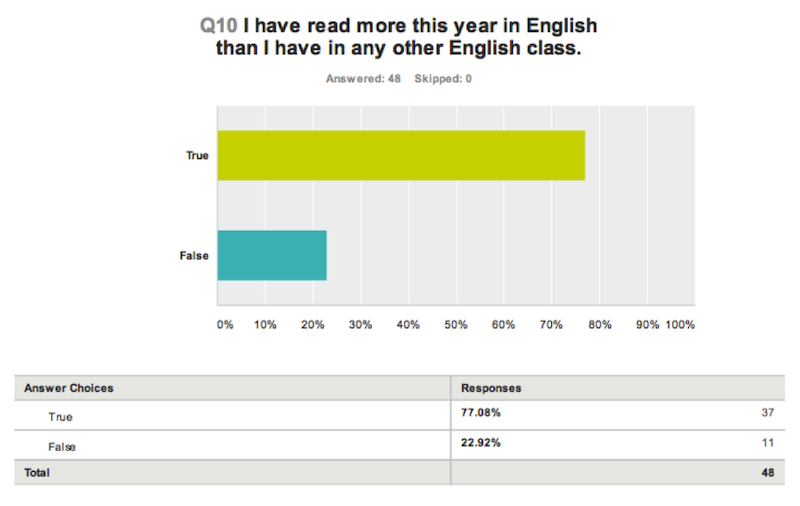

77% of students said they had read more in my English class than any other English class (see Figure 2).

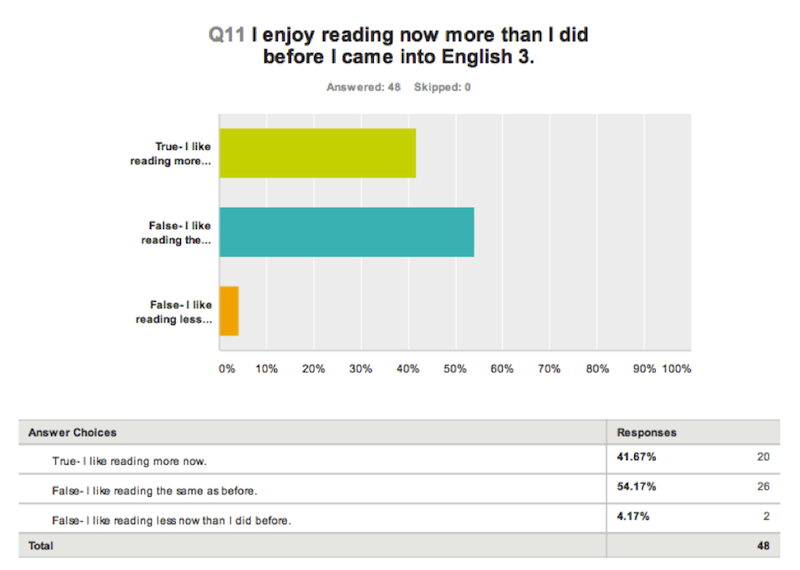

When asked if they liked reading more or less after participating in Reading Zone throughout the school year, 54% said they liked it the same amount, but 41% said they liked reading more than they used to (see Figure 3).

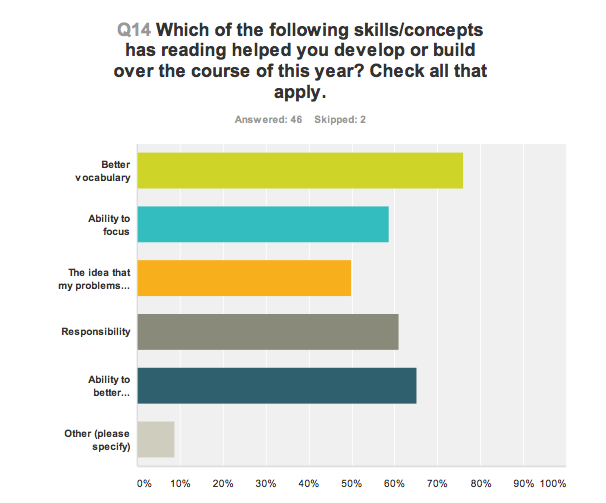

The students who completed the survey also attributed a number of new or strengthened skills to their increased reading: a better vocabulary (76%), the ability to focus (59%), the idea that their problems aren’t as great as they thought they were (50%), increased responsibility (61%), and the ability to better understand others (65%) (see Figure 4).

Learning from the Experts

I wanted to do better. Half an hour of independent reading a week was good, but I wanted my students to have more reading stamina and more choice in their own education. I wanted them to love reading—to obsess over books— to a degree that matched my own passion. So that summer, I read about reading. I read the rest of Atwell’s Reading Zone: How to Help Kids Become Skilled, Passionate, Habitual, Critical Readers (2007), which stresses the need for an environment where reading is modeled, valued, and enjoyed. I read Kelly Gallagher’s Readicide: How Schools Are Killing Reading and What You Can Do About It (2009), which discusses the ways in which the over-dissection of texts kills students’ love of literature. I read Donalyn Miller’s The Book Whisperer (2009), which is one teacher’s story of making her curriculum genre- and choice-based. I supplemented these books with other nonfiction titles about resilience and grit, the most notable being How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character by Paul Tough (2013).

I also spent time scouring thrift stores for books for my classroom. I bought books that I had enjoyed as a teenager, titles from the best sellers list, and anything else I thought my students might enjoy. I read a good number of them, too.

Findings

Determining Assessability

I bet that, now, some readers are thinking “That sounds like it took a lot of time and money. Was it really worth it?”

Part of me—the part that looks at the Pennsylvania Value Added Assessment System (a data analysis system that measures growth and projected growth) and the multitude of other acronyms used to assess our schools and our students— is tempted to wait to answer this question until their Keystone scores (the scores from Pennsylvania’s state standardized test) are available. Will my non-stop readers outperform their a-literate peers? Will I see a disparity between the scores of students who read eight books in the first quarter and those who read three books in the first quarter? Is it fair to contribute these trends to independent choice reading, or can we claim that my students both test well and enjoy reading because of their intelligence, their drive, or some other innate characteristic?

But the other part of me—the teacher who values her students as individual, intellectual human beings, the teacher who has been there since before my Praxis exams and my hours of professional development—is sure that, yes, it was definitely worth it. I can see the value of choice reading and independent reading on my students’ faces every day. I can hear their disappointment if we have to read for a shorter amount of time than they had expected. I can tell that they are grateful for their autonomy in the way they interact with me.

But in our data-driven profession, how do I prove it?

Student Feedback

I mentioned some of the data I collected from the 2013-2014 school year after initially implementing Reading Zone. Now, as the first quarter comes to a close, I am collecting new data from my 2014-15 students. Here are just a few of my 2014-15 students’ comments on Reading Zone as gathered from a quarter one survey (see Appendix B):

- “English class isn’t as boring. Reading Zone opens up your mind and prepares you for the day’s lesson.”

- “I like it a lot. It’s the only time of the day where everyone around me (and myself of course) can just relax and read or write.”

- “I am able to connect to a different life.”

- “I’m more level-headed and calm, in a way.”

- “I’ve been more calm and I pay more attention.”

- “It’s a great way to take a break from school and read a book.”

- “I think it’s peaceful. It encourages me to read more because everyone is so focused, quiet, and respectful.”

- “It has broadened my vocabulary. It expands my thinking skills, like as far as analyzing key thoughts or context.”

- “Reading has made me more calm and relaxed.”

- “Reading Zone is honestly my favorite part of the day. It helps me relax, which is the only time of day I can really have quiet and relax.”

- “I actually look forward to English class. Last year I used to sleep in English but now I want to be here and I honestly can’t wait to come back.”

- “Reading has made me a little more outgoing. I speak to people I never spoke to before because we are reading the same book.”

- “Reading Zone is a great idea. It’s a great way to relax and take your mind off everything and just read.”

- “I noticed that I’ve been reading more instead of watching TV.”

- “When I’m about to spazz [sic] on someone I usually just calm down by reading a book.”

Surely, these answers demonstrate a clear love for and appreciation of reading.

Some might argue that these responses are warranted from honors students, that they have adapted so quickly to Reading Zone because they were already in an advanced course. There may be some truth that that argument, but I found significant empirical evidence that Reading Zone made a difference even for non-honors students. For example, Lily [1], a student in one of my regular-track American Literature courses during the 2013-14 school year. She was an occasional reader before one of her classmates introduced her to romantic science fiction stories, and she devoured eight novels between March and August. There is also Mark[2], an English Language Learner who finished his first book in my class and chose to read Steinbeck on his own accord. And there is Michael [3] a student who never liked English until he was placed in my regular-track American Literature course, where he finished the first book he’d ever read under the desk while I taught a grammar lesson. Over the summer, Michael and I read two John Green books together, discussing them through text message, before he tackled the “17 Books To Read If You Liked The Fault In Our Stars” list on Buzzfeed (2014).

Classroom Management Benefits

One of my favorite things about Reading Zone, as illustrated by the aforementioned anecdotes, is the connections that it allows me to build with students. These connections have eradicated many of the classroom management issues I struggled with earlier in my teaching career. Though I have always recognized the importance of routines, I never before had such a stable routine as I do with Reading Zone: My students begin every class, every day, with between ten and fifteen minutes of reading. The students are comforted by the routine and the sense of security it brings. Furthermore, my students are extremely engaged in Reading Zone, which is not surprising as they choose their own books. This engagement limits common classroom disruptions like talking.

However, the most important classroom management tool that has come out of independent choice reading is the genuine relationships I build with students around the books we read. I tell my classes about what I’m reading and why I chose it; my students tell me about what interests them, and I recommend titles based on their preferences. We often share quick conversations about novels in the hallways or at lunch—an interesting tidbit from a book, a plot twist that shocked a student, a character who resonated with me. These simple exchanges lead to strong bonds: Rather than seeing me as a teacher who gives mandates, my students see me as a fellow reader with whom they can talk about books. I also see my students differently: Through these conversations, I see my students’ natural analytical strengths, remember their passion for learning, and better understand their lives and their personalities.

Implementation

My Five Rules

People—even the most reluctant teenagers—are, by nature, lovers of stories. Sometimes it takes the right story for them to realize that. Sometimes it takes the right person to show them.

What I’ve learned from the past two years of my Reading Zone experiment is that everyone is reader; out of the roughly two hundred students I’ve tried Reading Zone with, all of them have willingly engaged in it. But students need to be guided toward texts that resonate with them and be given the freedom and trust to explore these texts.

Teachers can do a great deal to contribute to this love of reading. Though everyone is different, I have found that following these five rules makes Reading Zone the most successful for me and my students:

- A book is a book. Students in my classroom read everything from Tony Story to Wuthering Heights. I don’t judge what they read, and I don’t censor it. (I do, however, reserve the right to call home and make sure their parents know what they are reading.) Different people have different interests, and they should be honored.

- I read, too. I read while they read, and I read a lot. The best way to lead is by example.

- We talk about our books. Sometimes we have a three-minute think, pair, share session after Reading Zone. Sometimes I transition from Reading Zone to class by telling them something about a book I am reading. Other times I pull a student aside in the hallway and recommend a book that I think he or she would like. It shows my students that I am invested in reading and invested in them—and it is a great way to strengthen relationships.

- We write about our books. We have readers’ notebooks where we (myself included—see #2) write about the books we read. Students are sometimes given specific prompts, but usually they can pick from a variety of thinking stems to use for their entries. Most of them are Reader Response theory-based, and this allows us to reflect, verbalize ideas and opinions, and connect our independent texts to our curriculum.

- We are free to ditch our books. Since Reading Zone is about choice reading, students have the opportunity to abandon a book if they are no longer interested in it. I mandate texts during all other parts of English class; this time is for them.

Other Strategies for Implementation

Though I have faced a few small setbacks while exploring how to implement Reading Zone over the last two years, the process has been easier than I initially imagined it would be. More importantly, though I knew it would benefit me and my students, I could never have predicted just how plentiful and important those benefits would be.

Implementing Reading Zone is not difficult, but it does take time and investment. For teachers considering implementing this strategy, I offer the following advice:

- Read some of the books mentioned above.

- Talk to your students about reading and find out what kind of readers they are as well as what they like and dislike about reading.

- Let your students see you with books, and let them hear you make connections aloud, in front of the whole class, between what you are doing in the classroom and what you are reading on your own time.

- Build in some time for independent reading in the classroom, and treat it with reverence; maybe even offer it as a reward periodically.

- Build a classroom library: ask friends for donations, scour thrift stores, create a Donor’s Choose project and share it widely.

- Tell students when you get new books, and make specific suggestions to specific students; it will build interest among everyone and other students will begin to ask your opinion on what they should read.

- Encourage students to talk together about what they are reading.

- Ask the students frequently for their feedback about the reading practices in your classroom, and take their advice: you will be surprised by the subtleties they recognize and the suggestions they can offer you.

To any teacher considering employing something like Reading Zone in his or her classroom: Just go for it! Such a program may take a while to establish, just as mine is still evolving. But reading, like learning, interacting, and building relationships, is not a definite, static process. These activities, like our students themselves, are dynamic—constantly changing. Don’t be afraid to try something new because it might not work out the way you want it to. Don’t worry that something may impede on your pre-planned curriculum and stop you from covering everything you are supposed to teach. Don’t be afraid to give up some of the control you have over your class and put it in the hands of your students. Experiment. Explore. Enjoy.

Conclusion

There are many questions teachers might when considering implementing independent reading: How can I get all of those books for my classroom? How can I get my students to sit silently for fifteen minutes and read? What if my supervisor doesn’t like this idea? But there is a more important question: In light of the academic benefits of reading we already know about and the social and emotional benefits we are continually discovering, how can you fail to make time for choice independent reading in your classroom?

We know some of the challenges that our students face on a daily basis. Outside of school they are plagued by family and community problems, bullying, and violence; they work job in the evenings and on weekends; they are tempted by all the vices our culture offers. Once in school, they have to deal with often uninteresting standardized curriculums and countless exams; they have to fight natural instincts and stay silently seated for hours at a time. Too often, we ignore each student’s interests and individuality; we forget that students, like teachers, are people.

If we are to get students invested in their own learning, we need to change the way we teach. If we are to help our city become more literate overall, we need to change the way we approach reading. If we are to educate for character and growth and success, we need to stop seeing our students as a standardized other, one on which we need to impose a certain kind of knowledge.

This is the best way I know to begin.

[1] Names changed.

[2] Names changed.

[3] Names changed.

[4]“Doubters and Believers” is an activity in which a teacher puts a statement on the board and has students move to one side of the room if they disagree with the statement (doubters) and the other side if they agree with the statement (believers). Then, students have a few minutes to discuss and debate about the statement.

Appendix A

1. How many books have you read (completely) since September of 2013? This includes books assigned for class and books you’ve read on your own.

0

1-2

4-6

7-9

10+

2. Check all of the assigned books that you’ve read.

Tom Sawyer

Of Mice and Men, Ethan Frome, or The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Their Eyes Were Watching God

The Bluest Eye, The Color Purple, To Kill a Mockingbird, Juvie, Jazz, or Malcolm X

Third and Indiana

3. Did you read any books that weren’t assigned by Ms. Dickerson this year?

Yes

No

Please list the other books you’ve read this year.

4. How many books did you read on the Kindle this year?

0

1

2

3+

5. How do you feel about Reading Zone?

I love it! It should be longer or we should have it every day.

It’s okay. I could take it or leave it.

I have it. You shouldn’t do it next year.

What other comments or suggestions do you have about Reading Zone?

Should students be able to read our assigned books during Reading Zone?

Yes

No

7. Should Ms. Dickerson make any of the following changes to Reading Zone?

Make it longer

Do it every single day (not just Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

What else would you change about Reading Zone?

8. I have read more this year in English than I have in any other English class.

True

False

9. I enjoy reading more now that I did before I came into English 3.

True—I like reading more now

False—I like reading the same as before

False—I like reading less now than I did before

10. Ms. Dickerson did things to make reading an enjoyable activity.

True

False

Explain what Ms. Dickerson did to either make reading enjoyable or make it not enjoyable.

11. I can see that reading more has helped improve my grades in other subjects besides English.

True

False

Explain your answer.

12. Which of the following skills/concepts has reading helped you develop over the course of this year? Check all that apply.

Better vocabulary

Ability to focus

The ide that my problems aren’t as big as I thought they were

Responsibility

Ability to better understand other people’s problems

Other (please specify)

Appendix B

1. List the books you have read so far in the first quarter. (If you remember, please list their authors and genres as well.)

2. What is your opinion of reading zone?

3. What is your opinion of our twenty-book requirement?

4. How (if at all) has reading zone changed your opinion of English class?

5. Explain any way(s) that reading more has affected your academics.

6. Explain any way(s) that reading more has affected your behavior.

7. Explain any way(s) that reading more has affected your personality.

8. What other benefits have you seen from your increased reading?

9. What lesson(s) have you learned from the books you have read this quarter?

10. What other information should Ms. Dickerson know about reading zone or the benefits of increased independent reading?

Atwell, Nancie. (2007). Reading zone: How to help kids become skilled, passionate, habitual, critical readers. New York, New York: Scholastic.

Calderon, Arielle. (May 27, 2014). “17 Books To Read If You Liked ‘The Fault In Our Stars.’” Retrieved from http://www.buzzfeed.com/ariellecalderon/books-to-read-if-you-liked-the-fault-in-our-stars#.bkDQAXV5B.

Gallagher, Kelly. (2009). Readicide: How schools are killing reading and what you can do about it. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse Publishers.

Miller, Donalyn. (2009). The book whisperer. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

Tough, Paul. (2013). How children succeed: Grit, curiosity, and the hidden power of character. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.