Teacher Networks in Philadelphia: Landscape, Engagement, and Value

Teacher collaboration has become an increasingly important lever for school improvement efforts. This is especially true in high-need urban districts, which struggle with capacity building in the face of significant teacher turnover, major shifts in curriculum and instruction, and scarce resources. This paper employs a mixed methods approach to analyze the landscape of teacher networks in a sample of district and charter schools in Philadelphia. Hierarchical linear modeling, social network analysis, and qualitative analysis are used to evaluate the types and functions of networks, school and teacher characteristics associated with participation in networks, and the value teachers associate with networks. The findings support previous research on the role of networks in improving school climate, broadening teacher expertise, and increasing job satisfaction and persistence in the field. Policy and research recommendations are offered to districts and schools.

The most effective teachers do not work in isolation. Instead, they foster collaboration and teamwork in order to continually improve their craft and deliver their expertise to ultimately impact the students they teach. Individual teachers working by themselves can result in a flattening of professional growth (Leana, 2011). In contrast, a growing body of research provides strong support for the importance of social capital—relationships among teachers—for improving public schools (Johnson, Lustick, & Kim, 2011; Leana & Pil, 2006; Leana & Pil, 2009).

Various terms have been used to describe social capital among teachers: collaboration, social networks, professional learning communities (PLCs), teacher networks, teacher professional community, teacher teams, collegial foci, and similar terminology (Coburn & Russell, 2008; Yasumoto, 2001). For the purposes of this research, we use teacher networks, broadly defined as “groups of teachers, organized both formally and informally inside and outside the school building/day, related teacher learning, support, or school improvement” (Niesz, 2007).

As such, teacher network opportunities take many different forms. Formal in-school teacher networks, such as teacher teams with structured meeting times, can be set up by grade level or discipline and across instructional or non-instructional building-wide issues (Liberman, 1995; Penuel et al., 2010; Spillane et al., 2007). Teachers also take advantage of out-of-school networks, whether through a university, district, or non-profit-sponsored group, for forming relationships and acquiring new ideas with others experiencing different school environments with their own challenges and strengths (Niesz, 2007). These associations outside the school can be especially powerful for teachers who feel isolated within their school (Niesz, 2007). At the same time, informal networks within a school building are multitudinous and organic, taking place in hallways and during lunch (Baker-Doyle & Yoon, 2011; Penuel, Riel, Krause, & Frank, 2009). Virtual teacher networks are also growing in popularity (De John, 2013; Quentin & Bruillard, 2013; Schlager, Farooq, Fusco, Schank, & Dwyer, 2009).

The purpose of this research is to better understand the landscape of teacher network participation, broadly construed. We explore the networks of 183 teachers in Philadelphia in order to understand the range of network opportunities in which teachers engage, perceptions of network value, and factors that influence participation and value. Using a mixed methods approach, we find that teachers engage with a broad range of networks, both internal to and outside of the school, formal or informal in nature, and conducted online or in person. While these networks have unique values and benefits, we find that they are also interdependent, indicating that teachers’ engagement in networks for professional support is complex and driven by a wide range of factors, including school context, content area, and professional goals. This “bigger picture” of teacher network participation is instructive for both policy and future research.

Research on Teacher Networks

Research often conceptualizes networks as important relationships that constrain or enable the flow of a wide range of both physical and intellectual resources, including knowledge, materials, ideas, and practices (Baker-Doyle, 2011; Coburn & Russell, 2008; Cole & Weinbaum, 2010; Coutinho & Lisbôa, 2013; Daly, Moolenaar, Bollivar, & Burke, 2010; Frank et al., 2004; Levine & Marcus, 2010; Penuel, Riel, Krause, & Frank, 2009; Penuel et al., 2010; Spillane, Hunt, & Healey, 2009). Formal network structures, including school- and grade-level learning communities, can provide “opportunities for reflection and problem solving that allow teachers to construct knowledge based on what they know about students’ learning and evidence of their progress” (McLaughlin & Talbert, 2006). Informal teacher networks can help teachers navigate school politics, cope with reforms and changes, and locate support, all of which have been found to be predictive of retaining high-quality teachers (Baker-Doyle, 2010; Penuel, Riel, Krause, & Frank, 2009).

Network participation has been positively associated with a number of outcomes for teachers and students, including teacher retention, expertise, and leadership to reform implementation and student academic outcomes (Anderson, 2010; Baker-Doyle, 2010; Daly, Moolenaar, Bollivar, & Burke, 2010; Leana & Pil, 2009). Teachers who find a network of colleagues with whom they can discuss their professional practice—either inside or outside their school—are more likely to be engaged in improving their practice and actively contributing to school-wide reform (Spillane & Louis, 2002). Finally, students show greater academic gains when their teachers report frequent conversations with peers and when there is a feeling of trust or closeness among teachers (Leana, 2011). For example, Moolenaar (2012) found that the pattern of social relationships among teachers contributes to student learning, teachers’ instructional practice, and the implementation of reform. Well-connected teacher networks have been associated with strong teacher collective efficacy, which in turn contributes to student achievement (Moolenaar, Sleegers & Daly, 2012).

At the school level, schools organized as communities of practice have been shown to promote greater teacher commitment and more student engagement in schoolwork (Bryk & Driscoll, 1988; Rowan, 1990; Moolenaar, Sleergers, & Daly, 2012). Lee, Dedrick, and Smith (1991) examined the effect of the social organization of schools on teachers’ efficacy and satisfaction and found that principal leadership, communal school organization, and teacher environmental control were associated with efficacy. Using nationally representative high school data, they found that achievement gains were significantly higher in schools where teachers undertook collective responsibility for learning. McLaughlin and Talbert (2001) similarly hold that professional communities in high schools influence professional satisfaction and instructional practice.

While this body of work consistently reveals the benefits of teacher networks in supporting student and teacher outcomes, there is less evidence about the range of networks in which teachers participate, the value teachers place on those networks, and the factors that influence participation and value. We refer to this as the “landscape of teacher networking” and it constitutes the focus of this research. We approach this work as researchers in an organization that has engaged in programmatic and policy efforts related to teachers and teacher networks in Philadelphia for over two decades. Our ongoing work with teacher networks has highlighted their critical importance to teaching and learning conditions and thus motivated this research direction. Moreover, as thought partners to policymakers and conveners of teachers and other education stakeholders, we realize the urgency of Philadelphia’s funding and school conditions, and hope to redirect and shape conversation to both take advantage of teachers’ existing capacities and to make Philadelphia a better place for teachers to work. We intend for this research to enhance the Philadelphia Education Fund’s understanding of and ability to support teacher networks in Philadelphia, as well as to advise stakeholders on ways to conceive of, help grow, and engage with, networks.

The following questions guide this work:

- What types of teacher networks currently operate in Philadelphia?

- What is the level of teacher participation in networks?

- What factors influence teacher participation in networks?

- Why do teachers value networks?

Methodology – Mixed Methods Approach

Understanding the landscape of teacher networks in Philadelphia demands a mixed methods approach. Qualitative or quantitative data alone is insufficient to adequately address our research questions. We employ a convergent parallel mixed methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011) for the purposes of complementarity (Greene et al., 1989). Quantitative data are used to address our first two research questions by examining the frequency of participation in various types of networks, teachers’ self-reported network size, and variability in composition of teachers’ networks. Qualitative data are used to augment quantitative findings with respect to the first two research questions as well as to understand teachers’ perceptions of value and to identify factors that influence participation and value.

Participants and Research Context

We conducted a two-stage sampling process. We identified fifteen schools, purposively selected by neighborhood, grade configuration, and feeder pattern to be representative of a range of schools in the district. Sample school sites are distributed over a twenty-mile range, falling within eleven of the twelve Planning Analysis Sections of Philadelphia. Our sample includes three elementary schools, two middle schools, and ten high schools, including two charter schools and three selective admission district schools. We disproportionately sampled high schools because they employ larger numbers of teachers. On average, the schools sampled serve proportions of minority and free/reduced lunch eligible students similar to those served by the district as a whole. Our sample schools, however, were more likely to have achieved Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) (27%)[1] in the prior school year than district schools overall (13%).

Some teachers self-selected into the study while others were invited to participate by their respective principals. Our sample of 183 teachers was 68% female/32% male and averaged 5.6 years of teaching within their current school and 11.3 years teaching total, with 18% of the sample considered to be ‘new to teaching’ (<4 years of experience). The vast majority (86%) had earned a master’s degree or higher. Sixty percent (60%) of the sample taught in core subject areas (mathematics, English/language arts, social studies, or science); 15% taught special education or ELL; 16% taught an elective, related arts, or foreign language; while 9% identified with “other” as their teaching area.

Data Collection and Analysis

A single method of data collection was used to generate both qualitative and quantitative data. In-person interviews were comprised of a combination of structured and semi-structured items.[2] Structured items addressed individuals, groups, or events that served as professional resources, as well as characteristics of those resources. Semi-structured questions followed with the purpose of identifying and describing teachers’ formal and informal interactions within and outside their schools. Sample questions included: What kinds of opportunities are currently set up at (your school) for teachers to work with one another? With whom do you interact most? For what purpose(s) do you primarily interact? With what kinds of out-of-school opportunities are you involved during which you come into contact with other teachers? In total, 156 interviews and focus groups featuring 183 district and charter school teachers were conducted. Interview data were coded to quantify the nature of teacher network participation and to develop a working theory as to how and why teachers participate in networks.

Social network analysis. Interviews were coded to capture each individual resource teachers identified as contributing to professional growth and learning. These resources are termed alters in a teacher network and coded [3] for the following characteristics:

- Was the alter identified as an individual, a group/team, or an event?

- Did the teacher interact with the alter as a result of a formal structure (e.g., grade level team meeting)?

- Did the teacher interact with the alter informally (e.g., within a relationship established on his/her own)?

- Was the alter part of the same school community (“in-school”)?

- Did the alter exist outside of the teacher’s school community (“out-of-school”)?

- Was the relationship with the alter carried out primarily in person?

- Was the relationship with the alter carried out primarily online or through other media?

The resulting dataset yielded 1,551 alters, identified by 146 [4] teachers for whom interviews included sufficient detail to characterize their networks. Based on the alter data set, ego network statistics were generated. Ego network statistics characterize each individual teacher’s network behavior. Using E-Net software (Borgatti, 2006), we produced composition statistics that proportion each teacher’s network to informal, formal, in-school, out-of-school, online, and in person. We also calculated network size [6] for each teacher and produced descriptive statistics of alters as well as teacher network composition statistics.

Because teachers are situated in schools—environments that influence professional behavior—we considered these data to be multilevel, with teachers nested within schools. We use hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to explore teacher- and school-level characteristics that may explain variability in teacher network behavior. With composition statistics as dependent variables, we ran null (empty) models to first determine the proportion of variability in behavior attributable to teachers and to schools. The resultant inclusive model contained the following teacher and school characteristics: experience level, subject area taught, grade level taught, percent of students eligible for free/reduced price lunch (school-wide), and AYP status (school-wide).

Qualitative analysis. Interviews were coded and analyzed through an iterative process using Atlas.ti. An initial set of a priori codes were developed based on themes found in the teacher networks literature and matched to research questions on network landscape, school and teacher characteristics, and value. Network landscape and participation codes included network type (formal or informal), network “location” (in-school, out-of-school, online), and additional participation codes (desired networks, sources of networks). School and teacher characteristics included school environment (leadership, autonomy) and teacher descriptors (teacher experience, instructional area, personality). Codes related to value include network purpose (classroom management, content, pedagogy, tools and technology, student support) and value assigned (positive, negative, neutral, preferred/ideal). The team[7] coded a sample of interviews with high inter-rater reliability (>85%) and proceeded to code all interviews. Data were then analyzed using a cross-case synthesis technique (Yin, 2010) to identify patterns and themes. Researchers drafted summative memos for each school and redistributed those memos to the research team, with multiple members reviewing and providing comments on each memo. The team then documented similarities and differences in teacher networks across schools.

Results

Types of Networks and Level of Participation

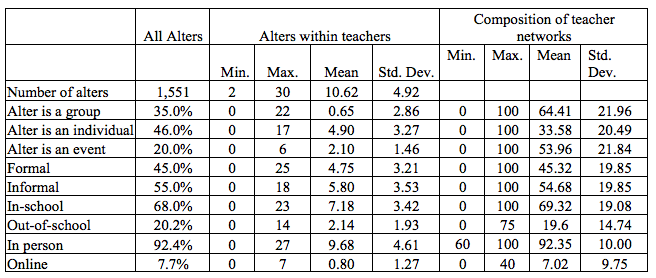

Table 1 characterizes the population of 1,551 alters, characterizes individual teacher behavior (both as an absolute value and as a proportion of network), offers insight into the networking activities of teachers in Philadelphia, and provides a deeper understanding of the networking landscape in Philadelphia.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, teacher networks

Teachers in our sample identified an average of 10 alters or resources as part of their professional networks. Thirty-five percent of reported opportunities for interaction were groups or teams (e.g., grade- group or department-level networks), and groups or teams comprised almost two thirds of teachers’ networks on average. An additional one fifth of all opportunities were events (e.g., external or district-led professional development), and on average events comprised more than half of teachers’ reported network opportunities. A slight majority of opportunities for professional interaction were informal. Similarly, a substantial majority of identified alters were opportunities or relationships within a teachers’ own school. Only one fifth of identified networks were located fully outside of one’s school, and very few (7.7%) were conducted primarily online. This suggests that, as compared to in-school networking, opportunities for networking outside one’s school are fewer and/or there are barriers to engaging in out-of-school networks.

In-School, Formal Networks

Our qualitative data confirm and expand on the above findings, revealing the following four prominent in-school network types: school-level networks, department-level networks, grade-group networks, and student support networks.

School-level networks were held anywhere from weekly to monthly. Teachers described these networks as “coming together” to discuss school-wide culture, teacher practice, deadlines, and tools. The meetings were facilitated by the principal and/or other school leaders.

Department-level networks were held anywhere from weekly to quarterly. Generally led by department heads and/or master teachers, they centered on lesson planning, curriculum alignment, announcements and administrative tasks, common language, and sharing of ideas. Some were narrowly focused on classroom instruction (e.g., a particular pedagogical strategy) while others addressed broader school-level functions (e.g., math department support for college essays of rising seniors).

Grade-group networks were the most frequently cited, held anywhere from daily to weekly, and were variously comprised of student support/special education teachers, teachers of record, entire grade teams, or parts of grade teams. They occurred during common planning time and served primarily to support lesson planning.

Student support networks, with a focus on supporting behavior, attendance, parent communication, and other needs, varied in incidence and outcome. Teachers, counselors, and other staff gathered to discuss students, supports, strategies, and interventions, often through the Response to Instruction and Intervention protocols. In some schools, compliance and documentation drove the support process and trumped the support mechanism. While a few schools built a student support function into department- or school-level networks, most schools did not.

In-School, Informal Networks

While our data collection included research on informal networks, these networks did not manifest strongly discrete functions or characteristics. As such, we did not treat informal networks as being distinct from one another in the way formal networks were. Informal networks were likely to take place in classrooms, in teacher lounges, and during lunch or before or after school. The purposes of informal networks varied from instrumental (e.g., reinforcing or asking questions on pedagogy, lesson planning, and school tools) to expressive (i.e., venting, catching up, and otherwise socializing). Teachers often took advantage of informal networks to seek advice from senior teachers and mentors as well as to build friendships.

Out-of-School Networks

The out-of-school network landscape was deep and diverse, but less clearly defined than that of in-school networks. Participation varied widely by teacher type and aspiration rather than by school structure. Out-of-school networks fit broadly into three areas: content, pedagogy, and teacher preparation; school systems/models; and teacher voice/policy. Other networks that did not fit into this group included those around community engagement, volunteering, project-based collaboration with students, conducting research, and teaching within teacher education programs. Examples of this broad array of out-of-school networks include: Teacher Action Group, Philasoup, Teach for America, Philly Youth Media Collaborative, Chemical Heritage Foundation, the New Teacher Network, the Philadelphia Writing Project, First Robotics, the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, collaborations with the American School of Bombay, USAID, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, EduCon, the West Philly Coalition for Neighborhood Schools, and many more.

Content and pedagogy networks focused on teacher expertise and knowledge, highlighting content expertise, teacher preparation, and subject- or grade-specific professional development. Various networks addressed pedagogy across multiple subjects (e.g., the Math + Science Teacher Forum), while others were individually tailored to specific subjects (e.g., the American Institute for Chemical Engineers). Content and pedagogy often overlapped, particularly in the context of subject-area professional associations. Content covered within networks fell well beyond the content students should know and understand, providing approaches to content instruction for teachers. These networks served as sources of new models, content, and lesson plans, replete with resources and tools to enhance instruction.

Policy and voice networks took a more expansive approach, highlighting school systems and tools and addressing school environment, student/teacher collaboration, student activities, school-wide leadership, networking approaches, and technology. These networks afforded teachers big picture networking outside of their own school or district, allowing teachers the opportunity to witness or share ideas locally, nationally, or internationally. Some networks focused on providing teachers avenues to promote voice (e.g., the National Writing Project), while other networks emphasized teacher policy action (e.g., Teachers Lead Philly, Teacher Action Group).

Influences on Network Participation

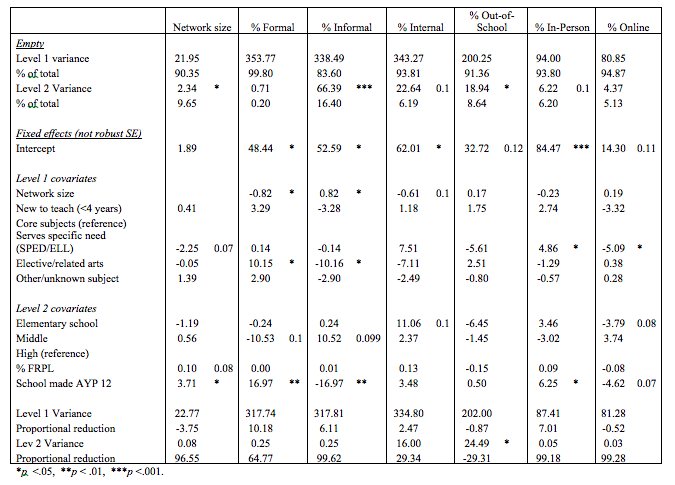

We see considerable variability in teacher network participation. This variability occurred both in terms of the level of participation (i.e., network size), and in the composition of those networks. Sizeable standard deviations relative to the mean reported for various types of network illustrate the significant variability in participation. Table 2 presents the results of the HLM analyses conducted to explore possible explanations for the observed variability.

Table 2. Results of HLM analyses predicting teacher network composition

The vast majority of variability in network behavior (84%-99%) occurs between teachers, and a substantially smaller portion of variability (0%-16%) occurs between schools. This suggests that characteristics of teachers are the most important predictors of network behavior. However, results offer few statistically significant findings with respect to teacher characteristics. There are no teacher-level predictors of network size, but results show a significant relationship between teachers’ network size and informal network behavior, indicating teachers with larger networks tend to have proportionally more informal relations than formal ones.

Elective/related arts teachers are more likely to participate in informal networks, which may be indicative of the lack of availability of formal networks for teachers in non-core subjects due to their smaller numbers within school buildings. There is some limited evidence that teachers serving students with special needs (special education, ELL) and those in elective/related arts positions may have slightly different network preferences. Special education teachers have slightly smaller networks and are less likely to engage online, as indicated by the statistically significant negative coefficients. However, the quantitative data offer no insight as to why this may be the case.

Experience (measured by whether a teacher was new to teaching, or had begun teaching within the past four years) and subject area (as indicated by classification as a core, special education, elective/related arts, or other subject teacher) were not predictive of network participation.

Network size was also not a consistent predictor of network behavior. Altogether, these variables account for 0%-10% of the variability between teachers, which indicates that most teacher-level factors influencing network behavior are not observed in our data.

These findings, however, explain little variability in teacher network behavior, suggesting unobserved characteristics are important predictors. Thus, additional research in this area is warranted. In contrast, though school context accounts for a small portion of variability, our models account for the vast majority of that variability for all dependent variables, save in-school/out-of-school network participation.

Grade level differences provide tentative evidence that elementary and middle school teachers engage in networks somewhat differently than high school teachers (most relationships approach significance with p<.1). In particular, elementary teachers appear to be more engaged in in-school networks, and less likely to engage in online opportunities, which may reflect elementary school culture and the structure of social capital therein. Middle school teachers are more likely to engage in informal than formal networks, a finding which may relate to policies around teaming or PLCs in middle schools.

Eligibility for free/reduced price lunch, a proxy for poverty and other challenging school conditions, only approached significance in the model predicting network size, with a small effect.

Making AYP was the most consistent predictor of variability in network participation. Schools that made AYP had teachers that were more active in networks, more likely to engage in formal rather than informal networks, and more likely to engage in in-person rather than online networks. This is not to suggest that formal, in-person networks led to achievement growth, but rather that school structures and social capital appear to be different in schools that made AYP.

To complement and extend our quantitative findings, we examined influences on network participation through our qualitative data analysis. These yielded explanations that focused on the combination of formality and location (formal in-school versus informal in-school versus out of school networks) as well as the interdependency between network types.

Formal, In-School Networks

In-school formal networking participation was largely driven by school and district policy and embedded structures rather than teacher choice. However, some flexibility existed, for example, in the case of department-level networks that had some choice surrounding their frequency of networking. Notably, schools that made available and required participation in networks saw a corresponding increase in participation. In particular, schools that met AYP exhibited a more robust set of formal networks that met more regularly.

Informal, In-School Networks

Teachers cited a combination of influences for participation in informal networks: proximity, expertise, and kinship.

Proximity. Teachers whose classrooms were close to one another were obvious candidates for informal networking, in part due to convenience and in part because teachers in the same grade group or department often worked on the same floor or hallway.

Expertise. Teachers seeking customized information would go to great lengths to identify those teachers with the expertise to answer questions. This included same-grade veteran teachers for developmental questions, within-department teachers for content questions, teachers across departments for cross-disciplinary collaboration, and teachers with common students for shared approaches to challenges surrounding student behavior.

Kinship. Teachers formed strong informal networks based on kinship. Teachers who identified one another as friends, often with the same experience level, entering cohort, age group, or grade group, would frequent each other’s classrooms. This occurred both in cases where specific expertise was requested (e.g., help with a lesson plan) as well as for more expressive, social purposes.

Out-of-School Networks

The out-of-school network landscape and reasons for participation were diverse and nuanced, yet still played a strong role in the teacher network landscape. Several teacher characteristics including content area and willingness to participate emerged as suggestive indicators related to out-of-school network participation. Additionally, a finding of lack of centrality of sources was a notable influence on out-of-school network participation.

Lack of centrality of sources. A key finding across sites related to network participation was the lack of centrality of network sources. Teachers learned about potential out-of-school networking opportunities sporadically: Sources included principals, fellow teachers (in- and out-of-school), former professors, listservs, newsletters from professional organizations, and online resources. Some teachers had multiple established sources while others looked for blocks of time (e.g., summer) to identify specific valuable networking opportunities.

Content area. In contrast to quantitative findings, qualitative analyses found evidence that teachers who lacked job-alike peers (e.g., lone special education, physical education, or visual arts teachers) often explicitly sought out out-of-school networks. With few local resources, including grade-group or department-level networks, or even a complete lack of content area peers, these teachers had extra needs as compared to other teachers and often looked for places to share content, pedagogy, and even meet social needs outside of the school day/building. The discrepancy in findings may reflect that our dichotomous categorization of teacher subject area masked important differences between subject areas or that the relationship between teacher characteristics and network participation is moderated by school contexts, such as network opportunities, faculty size, or number of subject peers. This is an area for further investigation.

Willingness to participate. Teachers who felt inundated during the school day noted their lack of energy to further engage outside of school. In contrast, teachers with the capacity to engage in out-of-school teacher networks as well as teachers with a broader view of engagement in teacher networks often positioned their experiences in terms of plural identities (e.g., serving as a change agent, teacher-leader, or teacher-researcher). These teachers explicitly desired to expand their knowledge and/or base, and thus looked outside of their own schools to engage in policy advocacy, conduct research, or teach diverse audiences. For these teachers, participation in out-of-school networks could be supplementary in certain domains, but was frequently complementary to in-school networks, allowing teachers to bring out-of-school knowledge back to their schools or simply provide more venues for participation and identity development.

Interdependent Relationships Between Networks

An additional finding regarding teacher participation in networks cut across all types of networks. In particular, while formal, informal, and out-of-school networks were all reported as valuable individually, the relationship between participation in these various forms of networks was revealed to be interdependent in that these networks variously supplemented or reinforced and extended one another. Given these two relationships—complementary and supplementary—we describe the connection between formal and informal networks as one of interdependency: Strong formal networks beget strong informal and out-of-school networks, while weak formal networks demand substitutive informal and out-of-school networks.

At schools with strong formal networking environments, informal networks complemented and extended the groundwork laid by formal networks. A discussion begun in a school-wide themed meeting might lead to two teachers informally designing an interdisciplinary history-art collaboration. Likewise, modeling various instructional practices in a department meeting might be followed up by several teachers informally or in an out-of-school network strategizing how to implement that concept. Recognizing this, teachers underscored the need for schools to be deliberate about collaboration and networking time. For gains to manifest and accrue informally, formal structures had to be built-in:

I feel like that - having gone through a couple of different graduate school opportunities since I’ve been here, I’ve learned more about education from my peers, and I’ve improved my practice more through talking to my peers. Which I do—which starts with the formal time. And it shows...a big part of what we value [here] which is collaboration, by building it into the schedule. And our principal always says, like, “If you value it, it should be in the schedule.” There should be a physical space or time where it happens. And I think it is hugely helpful.

In contrast, in schools with weak to absent formal networking, informal networks were crucial and often the sole vehicle through which to address teacher needs, often related to lesson planning and student support functions. Similarly, teachers lacking access to formal in-school functions often looked to out-of-school networks to compensate for the lack of professional development and social opportunities. As one teacher suggested: “If I were looking for out-of-school networks, I would be looking for something I could get there that I can’t get here.” However, despite the supplementary role formal and out-of-school networking played, informal networks could not fully supplant formal networks. Select networking functions, such as planning aligned cross-disciplinary activities or discussing larger school themes and goals, were less feasible or not feasible to accomplish outside of formal structures and processes.

Why Teachers Value Networks

Two of our research questions considered whether and how teachers valued various networks and which components were principally cited as associated with perceived value for teachers. A number of key findings emerged: universal value of networks, social value of networks, value of sharing of resources and expertise, and value of autonomy.

Universal value of networks

We found nearly universal agreement that networks are highly valuable, both in terms of expanding teacher knowledge and improving teacher satisfaction. Teachers desired, and highly valued, formal networks across a variety of contexts including school type, grade level, and instructional area, as well as informal and out-of-school networks. This was true for teachers in schools with strong networking opportunities as well as in schools with networks that were no longer in place.

In those schools that had previously existing networks eliminated due to budget and roster limitations, teachers reminisced about networking time and explicitly cited losses felt by the absence of various networks. One teacher lamented, “Unfortunately, there is no time built in to our days to meet either as a school or as a faculty. And that’s the problem.” Another stated:

What did I value most? That I was in touch with the teachers. They knew what I was doing, and I knew what they were doing. I would sit and listen, and they would talk about what their lesson plan was for the week, what they were covering. They would collaborate with each other like, you know, ask for suggestions on maybe activities, or what to skip, what to not skip, how to make the lessons better, what their experience in the past was with a particular lesson. And I felt like… I gained a lot from it, because I was like into everybody’s head, and I got all their good ideas, and I felt like I was really in touch with everything. Now, I’m very isolated.

A middle school teacher noted the absence of a student support network and the resultant duplication of efforts, misuse of time, and frustration of teachers and parents:

When we did the Comprehensive Student Assistance Process (CSAP), no one was responsible for doing all of the CSAPs. We worked on them together, sat together, and collaborated. Now, it’s just so dysfunctional. You could be calling the same parent twice. Instead of [parents] getting one phone call with, “This is the information that I’ve gotten from all five teachers,” now you’re getting five phone calls, because of [the teachers] just not being able to sit and talk.

Cross-disciplinary efforts no longer supportable by networks prompted similar frustration:

We could talk about students and collaborate with each other on lessons and ideas. One of the good things about last year was we actually worked as a team. For example, we had Kite Day, a multidisciplinary project. There was a math part, a literacy part, a social studies part, a science part. But in order to pull that kind of day off with 200 kids, you need all five teachers to do it together. We also knew who’s struggling, who’s not struggling. “Oh, she likes math, but she doesn’t like science. Well, science is more reading; how’s her reading grade?” And then you can talk. Now it’s like, I can’t do those kinds of activities, because we’re just not on the same page. We’re not even on the same day.

Another teacher expressed concern over losing such a network and the effects it would have on teacher communication and isolation: “If we didn’t have a grade group and we didn’t have those opportunities to talk, it would break down the communication even more. It’s very easy to become isolated.”

One school’s formal networks were removed before teachers rallied to bring them back:

They did away with—we used to meet, last year, every day as a team of teachers, to talk about students and to talk about policies and what behavior things are working and what aren’t, just to kind of all be on the same page. And they did away with that structure this year. So there was really no time for us to meet as grade-level groups. So the teachers voiced their concerns for months and months and months. And then finally when they realized that we really needed to be able to meet to talk about students we have in common, and solutions to issues that we’re having with them, we started having grade group meetings every week after school.

In the case of informal networks, autonomy was heavily valued, allowing teachers to efficiently target specific needs during the course of a day without being dependent on discrete, fixed, formal structures. One teacher explained:

I think it allows the communication to be a lot more— well, I don’t want to say more authentic, but just more natural. It’s organic, rather. That’s the right word. It’s organic. It’s what’s coming out of your emotions at the moment. In some ways it’s very much more productive, in that it’s what you need at that time.

Social value of networks

Networks were also valued for their expressive function, their role in promoting friendships, school climate, and other social and emotional needs. These factors were heavily cited by teachers discussing job satisfaction and an intent to persist at that school and in education. One teacher spoke to the role of networks combating isolation: “[The network] is also valuable because it makes you less stressed, like you’re not on an island. You know you have a support team.”

In highly-networked schools with highly-valued network environments, colleagues were described variously as friends and family. Here, network collaboration was described as “ingrained,” “a function of culture,” “leading to dedication,” “passion as payment,” and “so much better than money when it works.” These social benefits also had a key role in extending instrumental gains, gains related to instructional and professional rather than social activities. New expertise, resources, and practices were made more viable and implemented more consistently as a result of the shared sense of teacher collegiality, professionalism, and dedication.

The role of networks in strengthening relationships and promoting common understanding was central to network value. One middle school teacher noted:

The most valuable aspect of common planning time—when it existed—was the way we built relationships with each other. We also had times where we could ask for resources and to find out if we were all struggling with the same issue in our classrooms.

Networks were also highly valued for their instrumental role in connecting diverse groups of teachers that otherwise would have little time to collaborate, and similarly, creating a shared school culture and mission:

I mean, [the network] connects us—makes sure we’re all involved, we’re all on the same page, have a common language, understand where [we] are coming from. You know, we raise any kind of issues—positive, negative—in staff meetings, and I think it really helps us stay tight-knit.

Teachers spoke of the role of networks in combating isolation, thereby increasing job satisfaction and the intent to persist at one’s school:

I think teacher collaboration is the only way to go. It helps prevent teacher burnout. You're not working in isolation. I think working in isolation is very detrimental. It's detrimental to the teacher, which then in turn definitely affects [one’s] students. And how much more can you handle? And then, I think it definitely filters down to the kids.

It’s amazing how isolated you can be as a teacher. Even though we’re right next to each other, I can go through my whole day without seeing another teacher. So it’s nice to just sit down around a table and debrief… just to see other people and recognize common problems and find common solutions.

If I had friendships here I would want to stay longer. But right now I'm talking to more people at an outside school so it makes me want to be at their school.

Value of sharing of resources and expertise

Networks had a clear role in improving teacher knowledge and expertise related to pedagogy, classroom management, and curriculum development. Of particular value to teachers was space to share best practices as well as resources. One teacher noted: “Just to hear different ideas and different perspectives [during common planning time] is the most valuable thing for me.”

Another teacher expounded on the value of in-school formal networks for sharing practices, innovative ideas, and saving time:

You’re more aware of what everyone is doing, and if someone is doing a particular, working on a particular standard, a particular way, and it works for them, then if they’re willing to share it, it makes... you work smarter, not harder. That’s the best… way… to share, because we’re all here to do one thing and that’s to work with the kids and make them as good… as they can be. And if somebody’s doing something good and they’re willing to share, why should you beat yourself to replicate what they’re doing if they’re willing to share and make your life a little easier?

Out-of-school networks were similarly cited as offering “exposure to new ideas,” “ways to exchange ideas,” and even ways of “rethinking schools.” By providing “valuable different perspectives” and “philosophies on pedagogy” on the possibilities of teaching and learning in different classrooms and settings, out-of-school networks had the potential to broaden perspectives in ways that in-school networks did not, and were cited as “inspirational” and key for teacher engagement. One teacher noted: “Participation in networks and more specifically [network] leadership make me a much better teacher in that it forces me to constantly reflect upon my practice.”

Out-of-school networks held benefits specific to experience level. For novice teachers, out-of-school networks provided inspiration and insight into teaching approaches and culture, while for more experienced teachers, these networks served to reinvigorate interests:

If I was just like, “Oh God, another paper to grade,” I would have left. I would have been a statistic. But somehow I met the right people, and the right networks, at the right time. And I was like, “Oh.” Because you don’t get it at first; at first you really are like, “Oh God, these kids don’t listen. And I have to grade lots of papers. Why would anyone do this?”

Value of autonomy

Certain networks explicitly enabled teacher autonomy and leadership. For example, in some schools, teachers and master teachers led networks, set agendas, and self-selected onto themed committees. This autonomy was highly valued by teachers. Though autonomy has been seen as reinforcing traditional norms of the privacy of the classroom and teacher isolation, we found the opposite: that autonomy instead fuels collaboration. For informal networks, autonomy was also cited as critical, enabling teachers to seek out colleagues and address real-time needs with necessary flexibility. For out-of-school networks, autonomy was valued in that teachers had the freedom to pursue a wide scope of needs or desires through networks. In contrast, when autonomy was lacking, teachers frequently noted irrelevancy and inefficiencies:

[There was no connection—it was that] this has to be done this way and that, so [the District] may have to feel that every chance they get, they provided professional development in this particular area. Now they can hold you accountable for it.

Teachers spoke to the inefficiencies and dissatisfaction resulting from top-down networks with low levels of teacher autonomy:

I feel like I’m back in a college lecture. People stand up in front, they feed us information, and we leave. There is no expectation—well, I think it’s assumed that people will implement these things. And they don’t.

As teachers in this building, instead of the district telling us what we need, when they have no idea what we need—they don’t know. And they’re always coming up with, just something that’s already been handed down to us before. It just has a new name.

Teachers described the benefits of shifting from top-down toward more autonomous networks:

There’s a sense of autonomy, there’s a sense of empowerment, when teachers are able to drive and see connections on their own that naturally exist. Because subjects are not taught—I mean, subjects are taught separately, but that’s not the way they naturally occur. It makes more sense for teachers to find out what they have in common and to emphasize that.

Finally, formal networks that enabled teacher autonomy produced more authentic and productive networks. In these highly-networked schools with high levels of teacher autonomy, teachers felt like they had a stake in the school. This was critical for grade-, department-, and school-level networks as one teacher noted: “There’s always a need for consensus to be built around any policy.” Autonomous roles within networks enabled teachers to feel better informed and take ownership over professional needs and growth.

For the principal to leave that in my hands, I thought was a great honor, because he said, “You can run the show, and whatever you think, is.” So what I did was, I thought of myself as in two places: What do I want to leave with, as a participant? What is going to be useful for me that I can apply? And so then as I was trying to think of stuff that I could therefore turn around to the staff members, I thought of my own needs. How can I use this to make decisions in my classroom? I think it would be important for other teachers to know. So I try to have them leave with things that they can—concepts that they can go back with and can actually use.

Discussion

Networking behavior is complex and dynamic. As observed in this research, network participation lends itself to gradients wherein, for example, informal and out-of-school networks serve as extensions of formal networks. The use of mixed methods offered the research team more nuanced information about the relationship between various network types, functions, and factors associated with participation and value and ultimately provides a rich portrait of the teacher network landscape. We highlight four key findings of our analysis.

Network Participation is Broad and Varied

Between formal, informal, out-of-school, and online networks, teachers engage in a staggering array of networks with individuals, groups, and events. In these networks, educators serve as inheritors and producers of knowledge, teachers and learners, and local leaders and international experts. The networks, highly valued by teachers, help define an individual teacher or school and have a key role in shaping the conditions of teaching and learning, from classrooms to education policy. By conceiving of networks broadly, we consider the diverse forms networks can take and how these networks appeal to and support teachers. Several questions emerge: How can school leaders best employ teacher networks to support school climate and instruction? How can teachers best take advantage of available teacher networks, and how are those networks differently defined and used by novice versus veteran teachers for purposes such as professional growth and identity or stance development?

Interdependency of Networks

A further finding is the interdependency across and within network types. The value of, and participation in, informal and out-of-school networks was dependent on the existence and strength of formal networks. Moreover, interdependency existed within formal network structures themselves. For example, the capacity of a grade-group team to implement a new strategy or system would also be dependent on a school-level or department-level network. This finding reveals a complex landscape of structurally-impacted teacher and school preferences and needs. Moving forward, it is worth considering how this interdependency takes shape: relationships between formal networks, between formal and informal networks, and between in- and out of-school networks. How does this interdependency operate for teachers across grades and subject areas and for non-classroom educators and staff, and how does school context impact this interdependency and teacher network landscape?

Dominance of Formal, In-School Networks

Formal, in-school networks are arguably the dominant network structures, with approximately half of network opportunities formal in structure, two-thirds of which occur at a teacher’s own school. While informal and out-of-school networks were highly valued, formal, in-school networks were the bread-and-butter of professional development and co-creation of knowledge, constituting the basic school environment that enabled or disabled professional collaboration and growth. Moreover, the role of informal and out-of-school networks was dependent on the formal networking structures. As such, formal networks were essential for driving not just the day-to-day peer collaboration and tasks, but for setting up the conditions to enhance teachers and schools through informal and out-of-school networking. It may be valuable to identify the ways in which formal network structures build on one another and how informal and out-of-school networks similarly build on formal structures. We offer a number of questions to guide further inquiry: With this landscape in mind, how can school and district leaders capitalize on network interdependency to drive policy? In what ways do and can teachers take advantage of network interdependency to shape school culture, as well as one’s professional identity and role(s) within and outside of one’s school?

Networks as Central to Teacher Professional Development

While traditional professional development is often looked to as a primary vehicle for teacher learning, this work confirms that teacher learning and professional growth take place through a wide range of formal, informal, and in- and out-of-school teacher networks. Teacher networks, particularly those that are out-of-school and/or informal, often remain out of the limelight, and yet may constitute the majority of day-to-day learning teachers engage in. As such, they have a critical and understated role in teacher development. By conceiving of teacher learning in this way, we surface questions related to the complexity of organizational learning and social capital that policymakers should consider. How can school and district leaders employ networks to enable and strengthen teacher professionalism? In what ways can networks produce new, valuable, plural identities for educators, including future school or district leaders?

Importance of School Context

Relatively few schools offered examples of each of the four formal network functions. While high-performing schools had ample networking time, some lower-performing schools[5] had little to no formal networking, often with a complete absence of common planning time and only the occasional mandated periodic professional development offering. In schools where the networking environment did not offer formal networking opportunities, the four network functions were—at best—rendered through informal settings or, less ideally, excluded from the school’s networking environment and capacity altogether. As a result, when one or more of the network functions went missing, the absence was clearly felt by teachers, strongly impacting their work with students. This finding is the flipside of the high value attached to networks and the centrality of formal, in-school networks; for those schools for which networking landscapes were weak to absent, teachers struggled to perform daily duties, much less seek broader opportunities for professional growth and impact. Questions for further consideration include: What school conditions support strong networking cultures? In what ways can school leaders engage with teachers to co-create these conditions?

Research Recommendations and Limitations

A number of substantive research and policy recommendations emerge from our findings. We offer research limitations and two research considerations followed by key policy considerations for stakeholders involved with teacher networks and professional development.

Research limitations. While we believe this research offers a valuable big picture lens on teacher networks and offers important directions for policy and research, there are a number of limitations. First, the extent to which our structured interview questions capture the full range of network opportunities is unknown. Additionally, we do not distinguish between groups, individuals, and events, which not only results in a broad definition of “network” but also masks potential qualitative differences between the alters in teachers’ networks. Relatedly, we operationalize participation through quantity and composition, which offers only one lens on how teachers participate. We suggest frequency and relative value for each opportunity as alternative lenses for future research. Lastly, our sampling strategy captures a range of schools and teachers similar to the overall composition of Philadelphia and was likely to capture the breadth of networks available to teachers. However, the sample may not be truly representative of the district as a whole, nor does a sample drawn from Philadelphia generalize to districts with different characteristics. We suggest two approaches for network researchers:

Recommendation 1: Consider the networking landscape as a whole. First, our data demonstrate that teacher interaction is complex and not limited to informal or formal, in- or out-of-school, or in-person or online opportunities. Efforts to understand how teachers learn to improve practice that focus on any one of these dimensions is unlikely to capture the nature of the learning opportunities in which they actually engage. Further, these opportunities are often interdependent, indicating that research examining any one type of network must take into consideration the larger networking opportunities afforded to teachers.

Recommendation 2: Further examine teacher characteristics and teacher-school interactions. Second, future research should attend to the predictors of network behavior at the teacher level. Our quantitative analysis failed to explain variability in teacher behavior, yet our qualitative analyses suggest teacher characteristics (e.g. subject area) are influential in network decision-making. Further investigation of the factors affecting teacher participation in networks is warranted. Relatedly, our findings suggest that school networking context is influential on network participation. Given that opportunities vary by school, we hypothesize that school conditions may moderate the relationship between teacher characteristics and network participation. Future research in this area may offer a more nuanced understanding of teacher network behavior.

Recommendation 3: Deepen knowledge of formal and informal networks. Given the finding on interdependency of centrality of networks to teacher experience, it is important to better understand specific mechanisms within networks that enable professional as well as social outcomes. How do these networks form, what is done in them, and what purposes do these networks and their components serve? More importantly, how do these networks translate knowledge, resources, and capital through groups of teachers? While there exists a body of research on this subject, it is not rendered through a lens of network interdependency. Evaluating the mechanisms that enable productive networks and network cultures is critical for school and district leaders who aim to create productive network spaces.

Recommendation 4: Apply a range of methods. Finally, our data offer two distinct lenses on teacher network participation. Social network analysis affords an opportunity to explore teachers’ individual networks and their composition. The measures selected here have been instructive, but alternatives, such as frequency of interaction (a measure of strength) or heterogeneity (an alternative measure of composition) would extend our understanding of network behavior. Additionally, mixed methods research has been a powerful tool, offering complementary evidence to answer our research questions but also creating new directions for research and theory. For example, qualitative and quantitative findings yielded different results regarding teacher characteristics as drivers of network participation. Further, qualitative data yielded additional types of networks and network functions not operationalized in the quantitative analysis. Quantitative research can, in turn, help quantify and confirm the various benefits suggested by teacher’s valuation of networks in the qualitative analysis (i.e., impacts on teacher satisfaction, retention, and instruction). Finally, a mixed methods approach could be valuable not only for classroom teachers, but also for additional educators, such as school leaders, counselors, and nurses, as well as for understanding the connections between these alternative networks and the typical classroom teacher networks.

Implications/Policy Recommendations

A feeling of isolation among teachers is still the prevailing norm, and opportunities to build a network for support are essential in combating this feeling. Participation in teacher networks is closely tied to school culture and persistence in that networking improved culture, and highly-networked schools supported more meaningful collaboration and increased persistence.

Our findings suggest several policy considerations and recommendations:

Intentional design of network structures. With high variation among school-level networking environments despite consistently high and diverse reasons for value attached to participation in networks, it is important for network providers (i.e. districts, charter operators, and schools) and leaders to be intentional in designing space, resources, and structures for networks. School leaders have a central role in establishing collaborative climates, in particular the formal structures and systems that embed networks into a school’s culture. These structures should include all four key formal network functions with sufficient frequency and coherence to enable formal, informal, and out-of-school networks to build on one another. Importantly, the high value attached to autonomy for producing effective networking and professional development should urge school and district leaders and teachers to co-design network opportunities. That is, collaboration and distributed leadership should not only manifest within networks, but also when creating those network structures, thereby balancing top-down intentional design with genuine teacher autonomy. Thoughtful design and implementation of network structures can greatly enhance outcomes as compared with ad hoc network planning or inadequate network structures. Our findings related to autonomy and the interdependency of informal and formal networks imply that schools can provide meaningful professional support by intentionally organizing structured opportunities around teacher needs and fostering opportunities (e.g., rostered time, communication and facilitation tools, and opportunities for teacher leadership and autonomy), thereby enabling informal and out-of-school networks to complement those structured conversations. Additionally, the finding that teachers without job-alike peers (e.g., lone special education, physical education, or visual arts teachers) may have little to no in-school formal networks for their content areas suggests that there is an opportunity for districts to create specialized cross-school networks. To enable these efforts, network planning resources and tool kits could be further developed to support the development of robust networking environments in and out-of schools, as well as online.

Conceiving of networks as paths for teacher engagement and leadership. Policymakers may need to reconceptualize the role of networks to realize their full benefit. Schools exhibit many accountability-driven policies while teacher collaboration remains underdeveloped and under prioritized. Despite this, the engagement of teachers in a wide range of out-of-school networks reflects the desire of teachers to collaborate and grow professionally both within and outside of their schools. Schools and districts should capitalize on this desire to enable teachers to drive their own growth. High-functioning networks can not only enhance individual teachers’ classroom instruction and professional skills, but can also help to reveal and formalize new roles for teachers. By enabling teachers to adopt hybrid identities (e.g., teacher-leader, teacher-researcher), policymakers can support teachers interested in enhancing their professional work while remaining in the classroom as well as identify talented teachers who wish to pursue roles as school or district leaders.

Increased access to out-of-school networks. Efforts should be made to strengthen and centralize access to out-of-school networks through networking information hubs, school leadership, or teacher network “ambassadors.” Teachers reported inconsistent and sporadic participation in out-of-school networks, used those networks for highly varied purposes, and learned of those opportunities through a decentralized and varied set of sources. Findings also suggest that teachers seek these opportunities to supplement or complement existing networks. Organizations seeking to offer professional support to teachers may be better able to do so and more effective in outreach efforts through creation of central mechanisms though which teachers can access the range of resources available to them. A central database of resources or teacher ambassadors who serve as point persons for out-of-school networking opportunities could help enhance pipelines to these resources. Further, school, district, and charter organizations could be strategic in creating professional opportunities by focusing on issues that are complementary/supplementary to what is occurring in schools. This can only be attained by developing strong and mutually beneficial relationships between schools, districts or charter operators, and out-of-school networks.

Additional supports for high-need schools. High-need, under-resourced schools need additional help to establish and maintain effective teacher networking environments. Evidence provided above suggests that teachers in struggling schools demonstrate different network participation patterns and are in need of this type of professional supports. The very schools for which networks would provide the most benefit, and arguably at lower costs than other policies, lack the capacity and social capital to construct network structures. These challenges are often exacerbated by teacher and administrator turnover that preclude long-term planning. Constraints such as limited staff and little to no common planning time force teachers to supplement absent and important networking functions through inefficient, redundant, and burdensome supplementary alternatives. Strategies to expand the availability of common planning time through creative rostering, for example, may be key to building social capital through networks in the schools that need it most.

Conclusion

Our research underscores previous research demonstrating a wide array of expressive and instrumental benefits associated with teacher networks, including benefits for teacher content and pedagogical expertise; school reform, systems, and models; teacher self-efficacy; student engagement; interdisciplinary collaboration; broader social engagement of teachers; improved school climate; and increased teacher satisfaction and persistence. Future research should help to quantify these outcomes to confirm that the value teachers attach to networks is fully realized for both teachers and students. Furthermore, our research conceives of network type and participation as interdependent and as a function of both teacher and school characteristics. While additional research can help enhance understanding of the teacher network landscape, characteristics affecting participation in, and the valuation of teacher networks, ample research already suggests that thoughtfully designing and embedding teacher networks within schools provides a set of powerful levers for teachers to positively influence teaching and learning.

[1] Characterized as such by a school’s failure to achieve Adequate Yearly Progress.

[2] According to criteria outlined by No Child Left Behind (NCLB), 2002.

[3] Due to school and teacher preferences, eight interviews were conducted as focus groups.

[4]Size was not weighted to consider whether the alter was coded as a group, individual, or event. While this may change the number of individuals in a network, we focus on network size as a measure of overall resources identified by teachers.

[5] Focus groups were not able to be accurately coded for social network analysis.

[6]A sample of four interviews were coded independently by a senior researcher and a research assistant and assessed for reliability. Coders reached agreement on >85% codes; the remainder of interviews were coded by the research assistant.

[7] The qualitative research team consisted of a senior researcher, research analyst, and three research assistants.

Anderson, L. (2010). Embedded, emboldened and (net)working for change: Support seeking and teacher agency in urban, high needs schools. Harvard Education Review 80(4), 541-572.

Baker-Doyle, K. (2010). Beyond the labor market paradigm: A social network perspective on teacher recruitment and retention. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 18(26). Available at: <http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/view/836>. Date accessed: 23 Jan. 2015. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v18n26.2010..

Baker-Doyle, K. J. (2011). The networked teacher: How new teachers build social networks for professional support. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Baker‐Doyle, K. J., & Yoon, S. A. (2011). In search of practitioner‐based social capital: A social network analysis tool for understanding and facilitating teacher collaboration in a US‐based STEM professional development program. Professional Development in Education, 37(1), 75-93.

Borgatti, S. P. (2006). E-network software for ego-network analysis. Lexington, KY: Analytic Technologies.

Bryk, A. S., & Driscoll, M. E. (1988). The high school as community: Contextual influences and consequences for students and teachers. Madison, WI: National Center on Effective Secondary Schools.

Coutinho, C. P., & Lisbôa, E. S. (2013). Social networks as spaces for informal teacher professional development: Challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 9(2), 199-211.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (Eds.). (2011). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Coburn, C. E., & Russell, J. L. (2008). District policy and teachers’ social networks. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 30(3), 203-235.

Cole, R. P., & Weinbaum, E. H. (2010). Changes in attitude: Peer influence in high school reform. In A. J. Daly (Ed.), Social network theory and educational change (pp. 77-96). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Education Press.

Daly, A. J., Moolenaar, N. M., Bolivar, J. M., & Burke, P. (2010). Relationships in reform: The role of teachers' social networks. Journal of Educational Administration, 48(3), 359-391.

De Jong, O. (2013). Empowering teachers for innovations: The case of online teacher learning communities. Creative Education, 3(08), 125.

Frank, K. A., Zhao, Y., & Borman, K. (2004). Social capital and the diffusion of innovations within organizations: The case of computer technology in schools. Sociology of Education, 77, 148-171.

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255-274.

Johnson, W., Lustick, D. & Kim, M. (2011). Teacher professional learning as the growth of social capital. Current Issues in Education, 14(3), 1-16.

Leana, C. & Pil, F. (2006). Social capital and organizational performance: Evidence from urban public schools. Organization Science, 17(3), 353-366.

Leana, C. & Pil, F. (2009). Applying organizational research to public school reform. The Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 101-124.

Lee, V. E., Dedrick, R. F., & Smith, J. B. (1991). The effect of the social organization of schools on teachers’ efficacy and satisfaction. Sociology of Education, 64(3),, 190-208.

Levine, T. H., & Marcus, A. S. (2010). How the structure and focus of teachers’ collaborative activities facilitate and constrain teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 389-398.

Lieberman, A. (1995). Practices that support teacher development: Transforming conceptions of professional learning. Innovating and Evaluating Science Education: NSF Evaluation Forums 1992-94, 67-78.

McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2006). Building school-based teacher learning communities: Professional strategies to improve student achievement. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Moolenaar, N. M. (2012). A social network perspective on teacher collaboration in schools: Theory, methodology, and applications. American Journal of Education, 119(1), 7-39.

Moolenaar, N. M., Sleegers, P. J., & Daly, A. J. (2012). Teaming up: Linking collaboration networks, collective efficacy, and student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(2), 251-262.

Niesz, T. (2007). Why teacher networks (can) work. Phi Delta Kappan, 88(8), 605-610.

Penuel, W., Riel, M., Krause, A., & Frank, K. (2009). Analyzing teachers' professional interactions in a school as social capital: A social network approach. Teachers College Record, 111(1), 124-163.

Penuel, W. R., Riel, M., Joshi, A., Pearlman, L., Kim, C. M., & Frank, K. A. (2010). The alignment of the informal and formal organizational supports for reform: Implications for improving teaching in schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(1), 57-95.

Quentin, I. & Bruillard, E. (2013). Explaining internal functioning of online teacher networks: Between personal interest and depersonalized collective production, between the sandbox and the hive. In R. McBride & M. Searson (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2013 (pp. 2627-2634). Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Rowan, B. (1990). Commitment and control: Alternative strategies for the organizational design of schools. Review of Research in Education, 30(4),, 353-389.

Schlager, M. S., Farooq, U., Fusco, J., Schank, P., & Dwyer, N. (2009). Analyzing online teacher

networks: Cyber networks require cyber research tools. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 86-100.

Spillane, J. P., & Louis, K. S. (2002). School improvement processes and practices: Professional learning for building instructional capacity. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, 101(1), 83-104.

Spillane, J. P., Hunt, B., & Healey, K. (2009). Managing and leading elementary schools: Attending to the formal and informal organization. International Studies in Educational Administration, 37(1), 5-28.

Yasumoto, J. Y., Uekawa, K., & Bidwell, C. E. (2001). The collegial focus and high school students’ achievement. Sociology of Education, 74(3), 181–209.

Yin, R. K. (2010). Qualitative research from start to finish. New York, NY: Guilford Press.