What’s Going Right? Language Play and Bilingual Identities in a Predominantly African American Dual-Language Classroom

This paper examines two language practices of students in a predominantly African American bilingual second grade class: language play and identity formation. Prevalent notions about legitimate language knowledge are visible in the school’s curriculum, language goals, and assessment requirements. Additionally, discussions about bilingual classrooms (and especially of African American students) are often framed by a deficit outlook: what the learners, teachers, or schools are not achieving. When one takes a closer look inside a bilingual Spanish-English class a different picture emerges. An ethnographic study and analysis of classroom interactions and personal interviews are employed to argue that what students actually do with Spanish points to the need for an expanded conception of language knowledge in this school and beyond.

KEYWORDS: bilingual education, foreign language, language play, identity, classroom discourse, dual language

Note: The names of all people, places, and other identifying details have been changed in order to protect the privacy of the research participants.

1. INTRODUCTION

Affluent and middle-class white communities have benefitted, economically, academically, and professionally, from access to bilingual[1] and foreign language education for decades (Valdés, 1997). Though dual-language and bilingual immersion programs have expanded in number over the past twenty years, this growth has been predominantly in the area of “enrichment” programs which cater to white, English-speaking students (Cervantes-Soon et al., 2017). However, scholars believe that bilingual education can be a revolutionary force in countering oppression in marginalized communities by providing greater educational equity, and/or allowing for the maintenance of students’ home languages (Trujillo, 1996). Indeed, there is evidence that bilingual language education can be a tool for addressing the wide disparity in opportunities between many students of color and white students in the United States (Holobow et al., 1991; Lightbown, 2007).

Certain cities are experimenting with providing opportunities for communities of working-class African Americans[2] to send their kids to bilingual schools (Gross, 2016). However, such an endeavor is still so new that there is, essentially, no research on practices, attitudes, or outcomes of this type of schooling. This study provides a peek inside of one such program to show that, even though the model of bilingual education is still evolving, students demonstrate meaningful engagement with this form of schooling. I will also interrogate a) what counts as language knowledge at this school, b) who is considered a good learner, and c) if this school is successful. I seek to display what I have learned from students and teachers during my research in a bilingual school, later positing how this knowledge might guide the future direction of one-way, bilingual education in communities near and far.

Research Site and Positionality

The study discussed in this article took place at New Leaders School, a Spanish-English, dual-language, charter elementary school in a large, northeastern U.S., urban area. The school is located in a majority African American, low-income section of the city. I conducted over seven months of ethnographic field research in two second-grade classrooms within the same Spanish-English dyad. Two groups of twenty-six- and twenty seven students spend half of each day in an English classroom learning English Language Arts and Math content and spend the other half of the day in a Spanish classroom learning Spanish Language Arts and Science content. Six students out of fifty-three identify as a race other than Black/African American. All of the students in these two classes appear to have learned English as their first language, though a survey of student/parent home languages was not performed as part of this study.

On its official website, New Leaders School calls itself a “partial immersion” and “dual language” school. Because there are 1% or fewer native, Spanish-speaking students school-wide, the bilingual program could also be described as “one-way” or “immersion.” For the purpose of this paper, I will use the term dual language to describe the New Leaders School model, and occasionally refer to its particular, one-way subtype. Though the intent of the Spanish section of this class is to be partially immersive it is not fully executed in practice due to the high demands on the teacher, the amount of classroom management needed, and the varying second language abilities of the students who are all English speakers.

Teachers at this school represent a wide array of cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Spanish teachers are comprised of a mix of native Spanish speakers from Spain and Latin America and U.S.-born native English speakers. English teachers, deans, and classroom assistants are diverse and identify as African American, white, South Asian, Middle Eastern, and other cultural backgrounds. In the two classes examined here, the Spanish teacher, Maestra Sonia, is a white, U.S.-born, English-Spanish, bilingual speaker. The English teacher, Teacher Brenda, is U.S.-born, multilingual, and identifies as a non-Black person of color.

Throughout my time conducting this study, as a White researcher and outsider to the New Leaders School community, it was necessary to consider my own biases and reflect on the effect of my presence in this class. To lessen the risk of ascribing my own perspective onto the reporting of the thoughts and beliefs of the participants, I employed several methods to obtain participants’ perspectives on the communication practices and social interactions I recorded and analyzed. First, I made an effort to forge strong professional and sometimes personal relationships with the teachers and students with whom I worked. I also aimed to be useful, first, as a classroom assistant, and second, as a researcher, in order to strive for an authentic experience as a burgeoning member of the classroom community. Furthermore, when considering interesting topics or patterns to explore, I was guided by what appeared and was explicitly said to be most important to the students and teachers, rather than what seemed interesting to me as an academic. Sometimes this involved cross-checking my own thoughts and ideas with the teachers and occasionally the students by asking them directly. In my analysis, I support and validate my findings with interviews and other primary source data. As a newcomer to the New Leaders School and as someone who does not identify as a member of the African American community, such considerations were especially vital to the substance and legitimacy of the work presented here.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW: RACE & SPANISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION

“There appears to be an assumption, hiding within the premises of much of this research, that the value of immersion programs for African American children—unlike for white children—is still in question” (Palmer, 2010).

Studies that focus on either race or African American learners within the context of U.S. second language education are scant. The few studies that have explored the participation and experiences of students from historically marginalized communities have primarily centered around English Language Learners (ELLs). Research on African American children in foreign language, immersion, or bilingual school programs are even fewer in number. Past scholarship focusing on marginalized students in U.S., bilingual education falls into three primary contexts: Latinx students’ experiences, African American students’ performance and attitudes in two-way bilingual education settings and underlying racial ideologies in bilingual education. There have been no major studies done on bilingual or Spanish-language education in predominantly African American schools. In light of this, I review below the relevant literature that pertains to African American children in Spanish language programs.

Race and bilingual education

The body of scholarship concerning race in bilingual education is more substantial than the number of works focused on specific populations like African Americans. In 1997, Guadalupe Valdés published her seminal article, “A cautionary note concerning the education of language-minority students,” which discusses in depth the state of bilingual education and the dangers of racial injustice within current models. More recently, scholars have followed Valdés’s lead by critically approaching the political and social forces behind language use in educational settings (Flores & Rosa, 2015; Leeman, 2005; Palmer, 2010; Rubinstein-Avila, 2002; Schwartz, 2014). Prominently, Rubinstein-Avila (2002) studied how implicit language hierarchies in dual-language programs create educational inequalities for minoritized Portuguese speakers in New England. Around the same time, scholars such as Leeman (2005) investigated the sociocultural power of language practices and explored how underlying ideologies affect which varieties of Spanish and English are deemed appropriate for education. More recently still, scholars have begun to center race in their critical examinations of language education. Schwartz (2014) performed ethnographic research in a U.S., Spanish-language classroom where underlying discourses of racial otherness organize the Spanish classroom around white students’ comfort. Flores and Rosa (2015) also center their critical examination of bilingual education programs and practices around race, critiquing the omnipresent discourse in language education that “standard” or mainstream language should be provided in addition to a student’s home language or dialect. This premise is critiqued by Flores and Rosa (2015), who point out that only certain groups of students are stigmatized for using “social” language. They conclude that this occurs because language practices implicitly and persistently racialize some students and not others. Next, I review a subset of the research on race and bilingual education which deals with African American students in particular.

African American students in bilingual education

Over the past three decades, several scholars have problematized diversity in language classrooms with concerns of inequity for African American students. Such studies have investigated issues in the areas of inclusion, opportunity, and achievement in and through bilingual education (Davis & Markham, 1991; Haj-Broussard, 2002, 2005; Moore & English, 1998). Early studies, exemplified by the work of Davis and Markham (1991), investigate causes for low rates of African American participation in college-level, foreign language classes such as concerns about the quality instruction, perceived lack of cultural relevancy, and limited travel experiences. Davis and Markham (1991) further examine student attitudes towards foreign-language learning to uncover how instructional environments may alienate some would-be learners from the field.

Moore and English (1998) conducted the first in-depth research on the actual language practices of African American students in bilingual education. Findings from this six-month ethnographic study of a middle-school Arabic-language class showed how culturally responsive, flexible teaching can produce successful and motivated second language-learners. Later, Haj-Broussard (2002, 2005) produced research in a similar vein that explored the numerous benefits of African American students’ early participation in French-language immersion including improvements in the areas of self-concept, peers’ perception of African American female students, and student-teacher interactions. From here, I will now examine the narrow field of research most closely matched with my research: African American students studying Spanish.

African American students in Spanish classrooms

There have been few studies that specifically look at African American participation in Spanish-language education, which aligns with the context of the present research project. Scholars have investigated Spanish-English bilingual schools that make intentional efforts to serve and include African American students and concluded that each program experienced degrees of failure in: student performance and retention (Krause, 1999), teacher attitudes and preparation (Bender, 2000), and adapting the bilingual model to meet the needs of low-income, African American students (Pratt, 2012; Wiese, 2004).

On the other hand, other researchers have found that bilingual education programs are, in fact, able to serve the needs of African American students better than English-only schools. Parchia (2000, as cited in Palmer, 2010) found that the parents of African American children in Spanish immersion programs held highly positive attitudes towards their students’ language and intercultural learning. In another study, Lightbown (2007) concluded that Spanish immersion education “provided a rich educational opportunity for two groups of students whose academic performance is a source of concern in many schools across the United States: English Language Learners (ELL) and African American students from low socioeconomic backgrounds” (p. 30). However, in each of these previous studies, the potential of bilingual education to produce both high academic achievement and cross-cultural awareness in African American children is left somewhat in question.

A gap in the academic discourse

Deborah Palmer (2010) recognizes an undercurrent of hidden bias in the research on African American students in bilingual education in pointing out the common assumption that, “the value of immersion programs for African American children—unlike for white children—is still in question.” In other words, most previous studies seem to leave uncertain the potential of second language education to benefit this group of children. She questions why such doubt should persist, given bilingual education’s explicit cross-cultural and multiliteracy goals and its record of producing high academic achievement for white students. In her 2010 study of a Spanish immersion school, Palmer used ethnographic observations to illustrate “the relationship between teachers’ deficit orientations toward African American children and the systematic exclusion of these children from opportunities to enrich their education” (p. 97). I seek to align the framing of my research with Palmer’s (2010) perspective which recognizes the definite enriching potential of bilingual education for all students.

III. METHODOLOGY & FINDINGS

My central approach in adding to the few studies which have sought to understand African American students’ unique second language (L2) learning contexts is an attempt to strip away the deficit lens through which most mainstream evaluations of bilingual programs and examine success of students and programs. My primary questions became:

- How is Spanish taught and learned in the New Leaders School?

- Who is and who is not considered a “good” Spanish speaker at the New Leaders School?

- How do students at the New Leaders School display their emerging, bilingual skills?

In order to investigate my questions, I attempt to understand how language use impacts social processes, such as identity formation, and vis versa. Below, I outline my research procedure and the major theoretical tools that I draw upon to interpret the interactional data gathered.

Linguistic Ethnography

This qualitative study of African American dual language students is situated within the broad, theoretical and methodological tradition of linguistic ethnography. Linguistic ethnography takes the viewpoint that large and small-scale social arrangements always come into being through a series of individual encounters and interactions. This methodology requires a bottom-up approach to information-gathering and analysis, which “studies the local and immediate actions of actors from their point of view and considers how these interactions are embedded in wider social contexts and structures” (Copland & Creese, 2017, p. 1). In this view, everyday conversation becomes the central unit of investigation to uncover how the “here and now” aspect of seemingly mundane moments and reflect the “there and then” of the outside world and past histories (Gumperz 1982, 1999). Linguistic ethnography is the systematic study of these everyday interactions using qualitative data-gathering methods; it forms the basis of my methodological approach to understanding what classroom interactions mean to participants and how these interactions may reflect and affect the social context.

In the next two sections, I will briefly review how I collected and analyzed the ethnographic data for this study. I will then introduce two theories related to language learning that informed the narrowing, coding, and focusing of my analyses: language play and imagined identities.

Data Collection

I gathered data over the course of seven and a half months, from August 2018 to March 2019. I served as a classroom assistant one to two full-days per week, working closely with the students and teachers of the two, coupled classes. My role was to be a “helper,” responding to teachers’ and students’ needs in such capacities as: classroom management, leading Spanish Language Arts activities, academic assistance, tutoring, grading, and filing. I spent the bulk of my time in the Spanish section with Maestra Sonia’s class. For my research, I recorded notes about daily happenings, anecdotes, and conversations as a participant-observer. I wrote notes during my lunch break or upon returning home after the school day, often adding-in my own reflections or questions during this time. I also conducted five semi-structured interviews: one with each teacher in the Spanish and English sections, two with students[3], and one with a pair of students, together. In addition to my body of field notes and recorded interviews, I collected student-generated schoolwork and art and captured photographs of the physical environment.

Data Analysis Approach

Once data collection was complete, I scanned all handwritten field notes and read them several times in order to note and categorize any emerging patterns, also known as “open coding” (Emerson et al., 2011). I then performed a second, more focused “coding,” holding in mind topics that I perceived to be important to key participants and searching for representative instances and encounters. I processed my data in this manner in order to introduce the “emic,” or “insider’s” perspective into my analysis beginning with the initial stage.

Interviews were audio-recorded on a personal device. Similar to the coding process of fieldnotes, I listened in an unfocused manner and took notes on major themes and patterns. I transcribed particularly salient sections of the audio in order to include direct quotations as supporting evidence in this article’s analysis.

Once I had organized the data according to the emergent patterns, I selected two codes from which to extract examples that fit best with my primary argument—that students use their Spanish knowledge in creative and flexible ways—which, again, is informed by participants’ emic understanding. These two codes identified are the constructs of language play and imagined identities, both of which will be discussed in detail in the following sections. In later sections of this article, I present data that show the reader what students in this class actually do with Spanish language and how this contrasts with prevalent perceptions about legitimate language knowledge at the New Leaders School. Namely, students use Spanish in flexible, creative, hybrid ways that showcase their linguistic skills and emerging identities as young, African American speakers of Spanish.

Theory 1: Language Play

Language that is used for the primary purpose of self-amusement or fun is often referred to in second-language development scholarship as language play (Cook, 1997). Although it is often considered out-of-line with classroom norms and language learning expectations, language play has been shown by recent scholars to not only be part of normal development (Larsen-Freeman, 2006) but indicative of growing linguistic competence in a second language. In fact, Broner and Tarone (2001) assert:

the more advanced the learner, the more capable the learner is of participating in [language play]. The making of rhymes and puns, teasing and ridicule, and the creation of imaginary worlds of fiction all become richer and more complex as the learner becomes more advanced. (p. 365).

Cook (1997) distinguishes between language play as manipulation of form, such as experimentation with sounds, rhythm, puns, etc., and manipulation of meaning, to invent pretend worlds and fictional scenarios. Double-voicing, or adopting someone else’s voice or language as your own, and the creation and use of different voices and identities by the student are important examples of both types of language play that are used for amusement and to tease, mock, and poke fun. When another’s voice becomes one’s own, language development happens. Mikhail Bakhtin (1981) wrote the following about this process:

Language, for the individual consciousness, lies on the borderline between oneself and the other. The word in language is half someone else’s. It becomes ‘one’s own’ only when the speaker populates it with his own intention, his own accent, when he appropriates the word, adapting it to his own semantic and expressive intention. (pp. 288–289)

Pomerantz and Bell (2007) note that language play is often devalued in L2 classrooms, in favor of officially sanctioned functional and transactional forms of language use. In spite of this, many students continue to take risks when it comes to creative expressive language use in the classroom. Taking a critical lens in their study, Pomerantz and Bell (2007) also point out that native speakers are often praised for spontaneous, playful language while L2 learners may be chastised or ignored. Further, implicit ideologies about language teaching set the stage for the construction of some learners’ speech as problematic, incorrect, or illegitimate. These ideologies will be further discussed in the Conclusion section of this paper.

The Spanish Language Arts (SLA) curriculum employed in the New Leaders School is heavily literacy-based and places emphasis on utilitarian vocabulary and grammar, such as a curriculum unit about places in a city. The students are young, aged seven to eight years old, and not averse to taking risks by using their brand-new language in a manner that is neither literacy-based nor purely functional. The following conversation demonstrates this type of speech:

EXAMPLE 1.

[excerpt from field notes, 11/9/18]

(a) Maestra Sonia: (in English) “Raise your hand if you think you know what hùmedo y seco [wet and dry] means.”

(b) Multiple students: (in English) “A hot place and a watery place”

(c) Student Scott, voluntarily: “No paraguas y sì paraguas!” [“No umbrella and yes umbrella!”[4]] showing off a vocabulary word from 1st grade.

This interaction took place during a science activity during the Spanish-language portion of the school day. In line (a) the teacher spoke in English to check for Spanish-language vocabulary knowledge. Several students responded in English with the various guesses in line (b). Scott, who is not normally considered one of the high achievers in SLA, raised his hand and offered up an imaginative and witty response in Spanish, as seen in line (c). Scott’s answer was not the “correct” one, according to the lesson plan; the teacher expected students to provide English-language translations of the two Spanish-language words in question. Scott’s eagerness, smile, and tone of voice during this interaction indicated that he knew this and was amused by his humorous use of the target language.

Scott’s use of Spanish is, instead, an act of language play through which he seems to amuse himself by subverting the expected use of the target language in order to make a joke. This small deviation was celebrated by Maestra Sonia, who laughed and mentioned this incident to me later to ensure I noticed it. While Scott’s instance of language play was sanctioned by the teacher, Scott still took a risk in creating his own space for experimentation and creative expression, since it could have just as easily been punished. Perhaps, because he is not a student known for participating in Spanish, any use of the L2 by Scott would be seen as positive. Though this playful language is not expressly used for its expected functional purpose, that is, to get the correct answer, it appears to correspond to a rich understanding of the concept of wet and dry climates in the target language.

EXAMPLE 2.

[Excerpt from field notes, 1/15/19]

(a) Maestra Sonia: (In Spanish) “¿Cómo es el papel de cera?” [“What is the wax paper like?”]

(b) Student Aiysha: (In Spanish) “...Es li-so (highly affected) [“...It’s smooth”] … like Takis …. No but Takis like kinda crunchy.”

Here, Maestra Sonia is again conducting a science lesson with the whole class, seated together on the rug. First, she passes around samples of different materials and then asks the students to describe them using key vocabulary words in Spanish. In this excerpt, Sonia asks the group what the wax paper is like. A few students raise their hands and offer different answers in English and Spanish with positive feedback from the teacher. Then, Aiysha excitedly joins the conversation, mixing Spanish with her home dialect, African American Vernacular English (AAVE, also known as Black English). She begins in Spanish, employing an AAVE accent, and then switches mid-sentence to AAVE to compare the wax paper’s texture to that of a snack food, Takis, which are extremely popular at this school. In the second half of her answer, Aiysha turns away from addressing the teacher and towards self-directed talk as she wonders aloud, bringing in a cultural reference and continuing on longer than expected. Takis (Figure 1) are rolled, corn tortilla chips with a spicy seasoning. Takis do not bear much resemblance to wax paper however, they are an extremely valuable social currency in this classroom. Here, the mere mention of Takis garners the positive attention of the other students, demonstrated by their turning towards Aiysha or laughing in response.

Figure 1.

Takis

As in Example 1, Aiysha is using this opportunity to experiment rather than to simply answer the question, though she does meet grammar and vocabulary expectations in Spanish. She purposely layers her own dialect, attitude, and accent onto her Spanish showing how she can manipulate and play with language forms for fun. Aiysha, like Scott, is not usually referred to as a skillful Spanish learner by the educators, though over time I observed her producing many phonologically and grammatically “correct” utterances in Spanish. In Example 2, Aiysha takes her communication skills one step further by double-voicing a Spanish vocabulary answer in a different language style for comedic effect and diversion.

Unlike Example 1, this instance of language play in Spanish was not praised by the teacher, rather, it was ignored, which is likely because Aiysha’s response took up additional time and appeared to veer off-topic from the lesson. However, when viewed from the language play framework put forth by Cook (1997), this use of double-voicing, pragmatic awareness of the audience, and flexible blending of varieties of Spanish and English shows Aiysha’s use of a range of language skills and mastery.

Theory 2: Imagined Identities

Bonny Norton (2013) has developed a powerful framework for thinking about the changing, multiple, overlapping identities of language learners. Norton’s (2013) conceptualization of identity is defined as “the way a person understands his or her relationship to the world, how that relationship is structured across time and space, and how the person understands possibilities for the future” (p. 4). Identity includes the ideas people have about their future selves and is also affected by the unequal power dynamics that exist in every human interaction.

Consequently, Norton (2015) places great importance on students’ imagined identities which structure their investment in learning and their language practices. How do students view their future selves? How might their language choices reflect this? Student participants at the New Leaders School produced spontaneous expressions of Spanish which give clear insight into these questions.

EXAMPLE 3.

[Excerpt from field notes, 1/23/19]

(a) Student Alexis: (thickly accented Spanish, playing/mocking) “Mil novay-cien-TOS -ben-tee-nu-AY-VAY” [“Nineteen twenty-nine”]

(b) Other students repeat Alexis’s affected speech and add playful hand motions.

Maestra Sonia had just given a short presentation in Spanish about the life of Dr. Martin Luther King. Prior to line (a), she told the class King’s birth year, 1929 which, in Spanish, is written mil novecientos veintinueve. She asked the class to repeat this year after her in Spanish. Student Alexis raised her voice above the rest of the class as she assumed an exaggerated AAVE- inflection in her response, as shown in line (a). She giggled, as did the other girls sitting near her. In line (b), the class repeated the year in Spanish again and the other girls began mimicking the stylized pronunciation used by Alexis adding in rhythmic hand motions.

Using shifts of tone and voice, Alexis manipulates Spanish in unique and innovative ways that reflect who she is and what kind of Spanish speaker she sees herself becoming. In this way, she begins to construct her new multilingual identity as an African American Spanish user. Strikingly, this interaction took place over the course of roughly one minute, yet it demonstrates the uptake of the hybrid language invented by Alexis since others imitate, repeat, and even augment her communicative repertoire.

EXAMPLE 4.

[Transcribed from interview 1/17/19]

(a) Student Aubree[1]: “Um...on...on… my paper over there (Aubree turns and points towards wall behind her where student classwork is hung on a bulletin board) like where the volcanoes and stuff are at, I said I wanted to mo... know more Spanish than the Mexicans.”

(b) Researcher: “Do you think that’s possible? To know more than somebody who learned it from their family when they were a baby?”

(c) Student Aubree: “Yes. Yes! Um...even if I can find one, I want to go to a Spanish high school...and…”

(d) Student Jocelyn: “And college.”

(e) Student Aubree: “Yeah.”

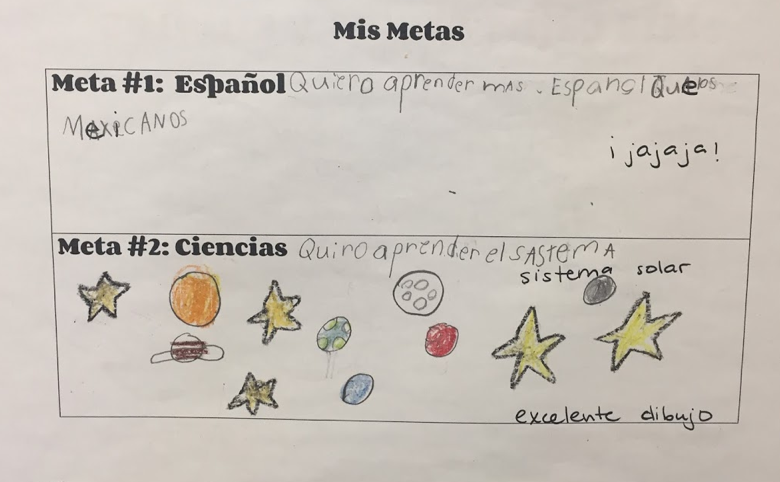

This conversation occurred during a paired interview with Aubree and Jocelyn for which I had prepared several questions to solicit their opinions about languages. At the end of the interview I asked both students in the pair to draw a picture of themselves speaking Spanish. In response (a), Aubree takes a moment to draw my attention to a piece of classwork (Figure 2) she had previously created which was posted in a prominent place on the bulletin board behind her. In this figure/drawing, we see an unambiguous expression of Aubree’s imagined identity as a future Spanish speaker, that is, one who speaks Spanish with more than native proficiency.

Figure 2

“Mis Metas” worksheet, Aubree

Note. Meta #1: Español; Quiero aprender mas Espanol que los Mexicanos [“Goal #1: Spanish I want to learn more Spanish than the Mexicans”]

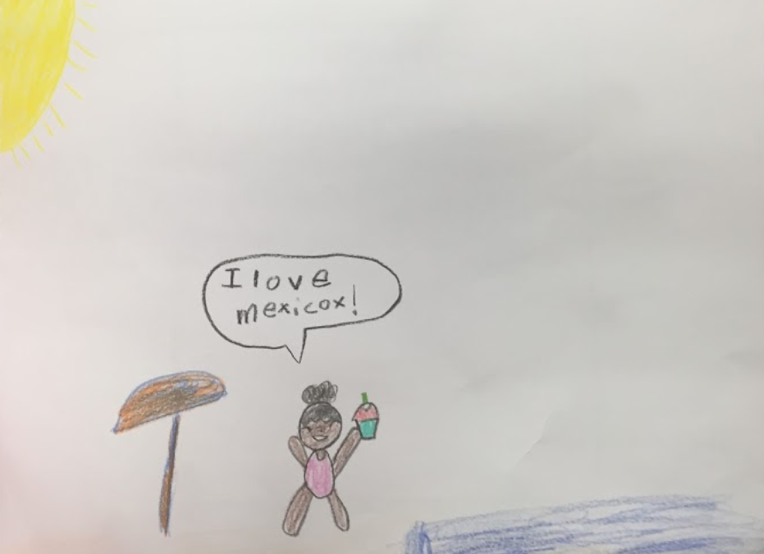

During the interview from which the previous conversation was transcribed, both students informed me that they had traveled to Mexico on vacation. Aubree mentioned her successful interactions with the Spanish-speakers in Mexico. Aubree produced another drawing in response to the final interview question, in which she places herself in Mexico, having fun (Figure 3). While it is somewhat ironic that Aubree drew an image of herself speaking English when prompted to “draw a picture of yourself speaking Spanish”, the message is evidence of her awareness that second languages are used for more than just learning rules and vocabulary, but also used for becoming a different kind of citizen as one acquires new language skills. This interview reveals Aubree’s communicative goals for Spanish language learning as well as her imagined identity.

Figure 3

Aubree, “Draw a picture of you speaking Spanish”

Note. I love Mexicox!(sic)

For readers concerned with educational outcomes, it is important to consider, in line with Norton’s (2015) thinking, that students’ imagined identities construct their investment in schooling. As evidenced in Aubree’s interview, Aubree is an invested learner with an imagined future identity as a highly proficient Spanish speaking citizen of the world. Norton (2013, 2015) notes that identities also illuminate dynamics of power at work within the social context embedded within the classroom. Though young learners may not yet be aware of these factors, curricular constraints, dominant ideologies about language knowledge, and implicit deficit views of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds and students of color create tension about the purpose of Spanish language education for marginalized students.

IV. DISCUSSION: What counts as second language knowledge?

In this section, I continue to interpret the classroom practices at the New Leaders School and paraphrase the voices of the classroom teachers in order to answer three central questions: What counts as language knowledge at this school? Who is considered a good learner? Is this school considered successful? In my interviews with Maestra Sonia, the educator in the Spanish section, and Teacher Brenda, the educator in the English section, they expressed frustrations with and the limitations of the execution of the model. The teachers’ frustrations are borne out of prevailing, societal ideas about language knowledge which are manifest in the curricula, assessment requirements, and administrative policies at New Leaders School.

The above examples pertaining to language play provide evidence that students at New Leaders School use their L2 in skillful ways that require significant, linguistic awareness. The data also show that, even at the young age of seven or eight years old, students are invested in learning Spanish via their imagined identities as future communicators and citizens of the world. Taking these two conclusions together, it stands to argue that this school’s dual-language program is, in fact, producing innovative, adept, and invested bilingual students. However, there are many interlocking social and structural factors at play that stifle linguistic creativity and restrict students’ opportunities for meaningful use of Spanish. Furthermore, due to pervasive privileging of written forms of language over both oral communication and language play, some students are positioned as less-capable Spanish speakers than others, since their linguistic prowess is not considered legitimate or valuable to school officials who are concerned only with the outcome of student literacy assessments.

The New Leaders School’s language arts curricula, for both Spanish and English classrooms, is heavily literacy focused. In an interview with Teacher Brenda, she noted that she was not in favor of the current curriculum of this academic year, adding: “We can’t get kids to read in a language they don’t speak […] we are putting the cart before the horse” (Interview, 1/23/19). She also brings to light that most financial resources are channeled towards English and Math while the Spanish program, which is what makes this school unique, is left underdeveloped. “We should be pouring everything into that Spanish curriculum […] we don’t have any oral assessments we don’t have any audio assessments, and those are the things we should be focused on” (Teacher Brenda, interview, 1/23/19). Maestra Sonia, in her interview, corroborates this point:

Personally, I think, that we, like, definitely in kindergarten and first grade, should be emphasis on speaking, and like veer away from so much emphasis on literacy...like biliteracy. But like the school’s idea is that, like, because they aren’t getting that much instruction in English language arts, like we have to support the comprehension skills and reading abilities of the kids in Spanish. Because of how the schedule is broken down. But I think that in an ideal world we should be focusing on bilingualism before literacy in Spanish. (Interview, 12/7/18).

Because it is a one-way, dual language program, there is also a tension created by the fact that there are no native Spanish-speakers in attendance from whom students would learn cultural components of bilingualism. This tension is compounded by the fact that the Spanish-language materials and media which are meant to supply cultural information feature almost exclusively non-Black characters. “We just got the kids picture dictionaries [...] which were really hard to find, diverse ones. Most of them were geared towards white kids learning Spanish. They didn’t have any people of color at all” (Teacher Brenda, interview, 1/23/19). The dictionary they eventually chose was from a British publishing company and included one illustration of a person of color, and was selected for this reason, according to Teacher Brenda. The curriculum also includes grade-level texts, such as short narrative or nonfiction passages to analyze, which Maestra Sonia does not believe the students “connect with very much” (Interview, 12/7/18). These interviews, along with my observations, paint a picture of a narrowly focused, literacy-based, Spanish-language curriculum that does not consider oral, communicative competence, let alone creativity, which is a normal part of L2 development (Larsen-Freeman, 2006). Because a curriculum tailored to African American L2 learners does not exist, the one used at the New Leaders School is ill-fitted to provide relevant, cultural information or experiences to African American learners, nor is the curriculum sufficient to compensate for the absence of Spanish-speaking peers.

In addition to the curricular challenges mentioned above is the influence of district and statewide assessments of officially sanctioned forms of language knowledge. As is typically the case, the New Leaders School’s success depends on students’ performance on standardized tests in reading and math. This dependency on standardized testing causes a greater investment of resources into English and Math than into development, support, and remediation of Spanish-language classes, despite the School’s mission to “emphasize second language acquisition” and “develop citizens of the world” (School website, 2019). Maestra Sonia noted that there are no district-wide tests for Spanish-language and wonders, “I don’t know if they have to, like, justify to the school district like how many hours of [English] language instruction, language arts instruction they are getting per day, um, when they submit their schedule” (Interview, 12/7/19).

In addition to curricula and standardized testing, top-down administrative policies also influence what language practices are valued at New Leaders School. In the School’s official information available online, there is a strong, neoliberal discourse present in the Statements of Purpose. For instance, the website states that Spanish language has been selected as the bilingual offering at the School due to its practicality and its common Latin-roots with the English language. Additionally, the benefits of Spanish-English bilingualism are described on the website in terms of future job skills and “long-term economic benefits” rather than for communicative, expressive or culturally integrative ends (School website, 2019). The School’s website goes on to address the potential concern that the bilingual program will interfere with Common Core standards and testing, emphasizing that State-level standards are blended into the curriculum and that the “partial immersion model” is best suited to reinforcing concepts in English in content areas. For the teachers at the New Leaders School, these ideas are salient in the lack of Spanish-focused professional development for teachers in favor of “data, data, data,” “going over looking at the curriculum,” and “nothing of any value, to me, related to language” (Teacher Brenda, Interview, 1/23/19). However, Maestra Sonia is able to partially circumvent this gap in professional development by meeting with the other Spanish-language instructors independently to talk about strategies for expanding communicative competence and increasing the quantity and quality of Spanish in their classrooms (Interview, 12/7/19).

V. CONCLUSION

It is unsurprising that when new or experimental bilingual schools come into existence, they often do not fare well when measured by the mainstream conceptualizations of language and knowledge described above. Partly due to a standardized testing culture, students experiencing marginalization and their schools are frequently noted for their supposed failures of language instruction rather than for their successes by the community, the media, and the federal, state, and local education departments. Matters are further complicated by the oft-unexamined racial and linguistic ideologies that permeate the national, educational landscape. High-stakes testing-culture imbues schools with a false choice between providing access to so-called “academic” forms of English (Flores & Rosa, 2015) and the nurturing of students’ unique ways of communicating as their full, multi-linguistic selves. Amid this discourse, L2 programs are often positioned as an extra or “nice-to-have” for allegedly English language-deficient, African American students, or as a mechanism for assimilation for ELL students. Communicative moments such as those in Example 2 and Example 3, which demonstrate students blending AAVE with Spanish in creative ways, oppose deficit discourses of AAVE that blame students’ home language varieties for interference with L2 learning (Dummett, 1984).

This chimera of administrative constraints amid persistent language ideologies about marginalized students calls for a broadened view of language knowledge in L2 education. Taking a closer look at student language practices reveals a wider scope of Spanish-language use that should be considered valuable via reconceptualized curricula, goals, and school policy. L2 classes can better reflect what students are doing well, their identities as language learners, and their individual L2 goals. From the data presented in this qualitative study, it is evident there is inherent value in knowing how to use Spanish language, especially in ways that fall outside of the purely literacy-based or practical-usage enforced by existing curricula.

Bilingual education has the potential to transform community schools and combat the wide opportunity gap between segregated urban neighborhoods. As acknowledged by school’s official mission and in interviews with teachers, dual-language programs could allow families experiencing marginalization, who are otherwise systematically deprived of economic and social capital, access to a form of schooling that has the potential to accelerate language skills and overall achievement for their children (School website, 2019). In order to truly combat this opportunity gap, fostering Spanish-language competence and emerging Spanish-English bilingualism ought to be a priority. Valuing Spanish-language competency beyond its ability to provide economic benefits and good test scores would help to support multicultural community building, empathy, and greater possibilities for the students’ futures as Spanish speakers in the modern world.

Implications for research

This study indicates for researchers, educators, policymakers, parents, and students that, though imperfect in many ways, students and teachers find the one-way, dual language model of schooling meaningful. Observers can see this in the form and quality of the everyday interactions of classroom members. This research adds understanding of an underexamined context to the inchoate conversation in urban education. For researchers concerned with the goings-on of bilingual schools, this paper provides additional insight into an example of such education. To this end, I hope this paper sparks an interest in continued research of one-way, bilingual education in communities experiencing marginalization.

Implications for practice

This study introduces an opportunity to think beyond the current institutional norms in dual-language and minority-majority education for improving pedagogical practices. The teachers I worked with at the New Leaders School are exceptionally passionate, social-justice-oriented educators who work under great pressure to conform to official standards while serving fifty-three children each day. Recommendations for changes in pedagogical technique imply that the norms of language teaching should be critically examined in order for dual-language programs such as that of the New Leaders School to succeed. In an interview, Teacher Brenda bemoaned the fact that “no one is in charge of the language curriculum” (1/23/19). With this statement in mind, I conclude with several, practical implications for language educators and administrators working in schools with students who experience marginalization.

Recommendations

1. Encourage and commend the expansion of students’ communicative repertoires in order to resist deficit framings of language practice. Adding professional development opportunities for educators of culturally responsive, language pedagogy is an important way to unify and shift classroom practices towards greater linguistic equity.

2. Create an L2 curriculum that builds on what students are already doing well or want to do well, including creative uses of language. This change requires an added awareness of existing student language practices and interests as well as individual monitoring and assessment of students, potentially incorporating some of the ethnographic techniques described in the Methodology and Findings sections above.

3. Introduce teacher training to build a common rubric for assessing bilingual communicative competence and creativity, in addition to biliteracy. For example, qualitative assessment could be used independently of mandated testing as an internal grading and measurement tool to place equal importance on the various functions of the L2.

4. Create opportunities for the formation of new and multiple identities of students as Spanish-language speakers, following the recommendations of Norton (2015). In practice, this could mean planning learning activities around students imagining their future selves. Such opportunities should also include students learning about diverse speakers of the L2. For example, in the context of this study, it would be helpful to include representations of Afro-Latinx Spanish-speakers as characters in lessons and/or real-life stories to inspire and represent students’ imagined, future identities.

[1] The terms “bilingual education” and “dual language education” are used interchangeably throughout this paper.

[2]Throughout this paper, I employ the term “African American” rather than the often interchangeable “Black” to fit with current literature. I also use “African American” to refer specifically to the U.S.-born population of students at New Leaders School, rather than the larger population of Black-identifying residents which may include immigrants.

[3] Written consent was obtained from legal guardians of minors who participated in interviews.

[4] All translations were done by the author.

[5] All interactions from student interviews were in English

REFERENCES

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981) The dialogic imagination: Four essays (M. Holquist, Trans.). University of Texas Press.

Bauer, E., Colomer, S. E., & Wiemelt, J. (2018). Biliteracy of African American and Latinx kindergarten students in a dual-language program: Understanding students’ translanguaging practices across informal assessments. Urban Education, 55(3) 331–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918789743

Bender, L. (2000). Language planning and language policy in an urban public school: The interpretation and implementation of a dual language program (Publication No. 9989573) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. Bell and Howell Information and Learning.

Broner, M., & Tarone, E. (2001). Is it fun? Language play in a fifth‐grade Spanish immersion classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 85(3), 363–379.

Cervantes-Soon, C. G., Dorner, L., Palmer, D., Heiman, D., Schwerdtfeger, R., & Choi, J. (2017). Combating inequalities in two-way language immersion programs: Toward critical consciousness in bilingual education spaces. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 403-427.

Cook, G. (1997). Language play, language learning. ELT Journal, 51(3), 224–231.

Copland F., & Creese, A. (2017). Linguistic ethnography. In K. King, Y. J Lai, & S. May. (Eds.), Research methods in language and education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education (3rd ed., pp. 339–351). Springer, Cham.

Davis, J. J., & Markham, P. L. (1991). Student attitudes toward foreign language study at historically and predominantly Black institutions. Foreign Language Annals, 24(3), 227–237.

Dummett, L. (1984). The enigma: The persistent failure of black children in learning to read. Reading World, 24, 31–37.

Emerson, R., Fretz, R., & Shaw, L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press.

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education, Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149–172.

Gross, N. (2016, November 22). Dual-language programs benefit disadvantaged Black kids, too, experts say. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/dual-language-programs-benefit-disadvantaged-black-kids-experts-say/

Gumperz, J. (1982). Discourse strategies (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

Gumperz, J. (1999). On interactional sociolinguistic method. In S. Sarangi & C. Roberts (Eds.), Talk, work, and institutional order: Discourse in medical, mediation, and management settings (pp. 453–471). Mouton de Gruyter.

Haj-Broussard, M. (2002). Perceptions, interactions and immersion: A cross-comparative case study of African American students’ experiences in a French immersion context and a regular education context. ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED476262.pdf

Haj-Broussard, M. (2005). Comparison contexts: African American students, immersion, and achievement. ACIE Newsletter, 8, 6–10.

Holobow, N., Genesee, F., & Lambert, W. (1991). The effectiveness of a foreign

language immersion program for children from different ethnic and social class

background: Report 2. Applied Linguistics, 12, 179-198.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2006). The emergence of complexity, fluency, and accuracy in the oral and written production of five Chinese learners of English. Applied linguistics, 27(4), 590–619.

Leeman, J. (2005). Engaging critical pedagogy: Spanish for native speakers. Foreign Language Annals, 38(1), 35–45.

Lightbown, P. (2007). Fair trade: Two-way bilingual education. Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada, 7, 9–34.

Moore, Z., & English, M. (1998). Successful teaching strategies: Findings from a case study of middle school African Americans learning Arabic. Foreign Language Annals, 31(3), 347–357.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation (2nd Ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Norton, B. (2015). Identity, investment, and faces of English internationally. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 38(4), 375–391.

Palmer, D. (2010). Race, power, and equity in a multiethnic urban elementary school with a dual-language “strand” program. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 41(1), 94–114.

Parchia, C. T. (2000). Preparing for the future: Experiences and perceptions of African Americans in two-way bilingual immersion programs. [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. School of Education, Harvard University.

Pomerantz, A., & Bell, N. D. (2007). Learning to play, playing to learn: FL learners as multicompetent language users. Applied Linguistics, 28(4), 556–578.

Pratt, C. (2012). Are African-American high school students less motivated to learn Spanish than other ethnic groups? Hispania, 95(1), 116–134.

Rubinstein-Avila, E. (2002). Problematizing the “dual” in a dual-immersion program: A portrait. Linguistics and Education, 13(1), 65–87.

Schwartz, A. (2014). Third border talk: Intersubjectivity, power negotiation and the making of race in Spanish language classrooms. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, (227), 157–173.

Trujillo, A. (1996). In search of Aztlan: Movimiento ideology and the creation of a Chicano worldview through schooling. In B. Levinson, D. Foley, & D. Holland (Eds), The cultural production of the educated person: Critical ethnographies of schooling and local practice (pp. 119-148). SUNY Press.

Valdés, G. (2015). Dual-language immersion programs: A cautionary note concerning the education of language-minority students. Harvard Educational Review, 67(3), 391–430.

Wiese, A. (2004). Bilingualism and biliteracy for all? Unpacking two-way immersion at second grade. Language and Education, 18(1), 69–92.