“In the Swell of Wandering Words”: The arts as a vehicle for youth and educators’ inquiries into the Holocaust memoir Night

Introduction

This article includes the script of a performance from the Communities of Inquiry Symposium at the Ethnography in Education Research Forum, March 1, 2014.

The event invited audience members to imagine the relationship of the arts, multimodality, research, and critical pedagogy, through an evocation of a community of adolescents’ and teachers’ arts-based inquiries into the Holocaust memoir Night by Elie Wiesel (2006). This performance attempted to trace ineffable aspects of Night through participants’ interpretive, embodied, and artistic responses. The resulting collaborative text addresses a range of issues, among them: the role of the witness; the inadequacy of language; the nature of faith; the challenge of adequately responding to survivors and victims of the Holocaust from individuals’ own socially-situated vantage points; the limitations and potentials of aesthetic responses to trauma; and the function of the arts in critical pedagogy.

The script presented here was developed collaboratively from vignettes that participants wrote from their experiences authoring curriculum for Night, exchanging letters with Elie Wiesel, and ultimately creating an exhibition, entitled After Night, of large and small-scale paintings on book pages from Wiesel’s (2006) text. This approach was inspired by the work of Tim Rollins (Berry, 2009), who invites youth to produce symbolic and allegorical paintings and drawings in response to—and on the pages of—texts ranging from classical literature to comic books. Guiding this performance, the script and the exhibition it describes, was a concern for the multimodal and moral dimensions of critical pedagogy. We chose to use the arts as a means of inquiry, with the intention of inviting “possibility, creativity, and imagination” (Harste, 2013) in ways that other pedagogical approaches—and other methodologies—may not (e.g., Simon, Campano, Broderick, & Pantoja, 2012). Following Maxine Greene (1995), this project was inspired by the idea that “[i]magination is what makes empathy possible” (p. 3).

Interwoven words and experiences of participants suggest how painting provided a means of surfacing individual and collective responses to Wiesel’s text. In both the artwork and performance, complex issues were induced, provoked, but left unsettled. As intellectual historian Dominick LaCapra (1996, 2004) notes, the Holocaust is an event that defies comprehension. Rather than deriving a universalizable meaning, the Holocaust is a site of historical inquiry that demands perpetually working through (LaCapra, 1996, 2004; see also Eisenstein, 2003).

A slim volume of unusual impact, Night proved to be a challenging text to work through. Published in English in 1960, Night is a record of Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel’s experiences in the Auschwitz and Buchenwald concentration camps from 1944 until his liberation in 1945 at the age of 16. Wiesel’s working title for Night was Un di velt hot geshvign: Yiddish for "And the World Remained Silent." In the book, Wiesel writes that society was then composed of three categories: victims, killers, and bystanders. As the title of the exhibition suggests, the After Night project approached Wiesel’s text as a starting point for inquiry rather than an end in itself, a catalyst for assuming a fourth positionality: that of activists who refuse to be silent or indifferent to human suffering.

Throughout his writings and public addresses, Wiesel has repeatedly appealed to audiences to assume activist stances toward injustice in the world. In his remarks on receiving the Lyndon Baines Johnson Moral Courage Award, Wiesel (2012) described what he called an 11th commandment: “Thou shalt not stand idly by whenever there is an injustice committed against the honor or destiny of a person or a people. Thou shalt not stand idly by. You must speak up. You must defend.” Never forgetting the Holocaust, Wiesel argues, entails a moral responsibility to refuse to remain silent in the face of any injustice, whether in Bosnia, Rwanda, or Darfur.

The After Night exhibition was held at a gallery in Hart House at the University of Toronto in February 2013. The artwork was produced over several weeks in January 2013 by 30 adolescents and teachers who worked together in a research collaborative called the Teaching to Learn Project (Simon et al., 2014). Founded in 2011, the Teaching to Learn Project has invited teachers and teacher candidates at University of Toronto to explore aspects of literacy education in urban schools together with middle and high school students. Research initiatives have included co-authoring curriculum for texts that explore social justice issues of concern to participating youth.

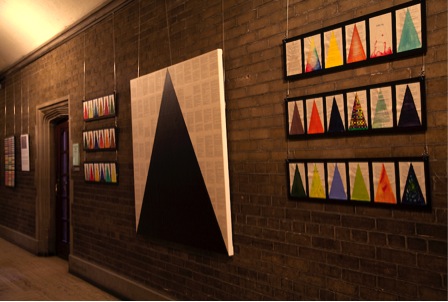

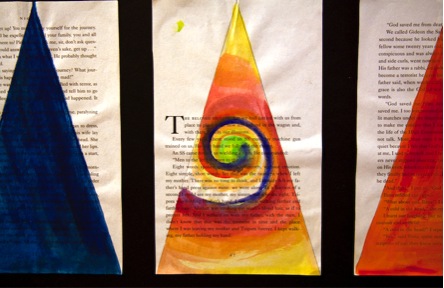

Paintings in After Night include images of triangles, the symbol Nazis used to demarcate undesirable individuals, painted on individual book pages in colors and patterns artists chose to represent their visions of diversity and solidarity (figures 1 and 2). In the exhibit, smaller works were interspersed with large canvases (5’ x 5’) covered in book pages, painted with translucent triangles of orange, purple, and blue, through which Wiesel’s text can be read (figure 1). Each large painting contains nearly the entire text—96 of 113 pages—of Night.

The impetus for exploring faith-based aspects of Night derived from the questions of students, including co-authors Julia, Kevin, and Antonino, who are members of a faith-based youth leadership group directed by co-author Anna. In letters they exchanged with Professor Wiesel, participating youth asked, “Why would God allow this to happen? What does it mean to have faith in the midst and in the aftermath of atrocities like the Holocaust?” In the letter he wrote in response, Elie Wiesel described his experience of faith in Auschwitz: “Even in the camps I never lost my faith in God. However, I protested against God’s silence. Yes, I still believe in God, but my faith is a wounded faith.”

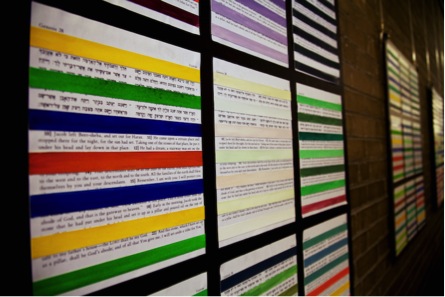

To explore the idea of faith visually, we used the symbol of a ladder from the biblical account of Jacob’s Stairway (Genesis 28:10-19), an image of faith in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Coloured strips were painted in gouache on bristol then cut and attached to pages of text from Genesis 28 in Hebrew and English. Ladders represent individuals’ images of faith—in divinity, in family, in humanity, and in community (figure 4).

The final painting in the exhibit contains the word “Kaddish,” the Hebrew term for “holy,” painted in charcoal and ashes on pages from Night (figure 3). This refers to one of the most significant prayers in the Jewish liturgy, the Mourners’ Kaddish, central to Jewish rituals of mourning. Perhaps counterintuitively, the Mourner’s Kaddish does not mention death. Rather it is a reaffirmation of faith and hope.

Like the Kaddish, this collaboratively authored script is both a memorial and an affirmation: an expression of solidarity with victims of intolerance and a shared faith in humanity.

Figure 1: Images of triangles. After Night exhibition, 2013. [Photograph by Laura Darcy]

Figure 2: Close-up images of triangles painted on pages from Night by Elie Wiesel (2006). After Night exhibition, 2013. [Photograph by Laura Darcy]

Figure 3: Viewing “Kaddish” painting. After Night exhibition, 2013. [Photograph by Laura Darcy]

Figure 4: Images of ladders painted on pages from Genesis 28:10-19. After Night exhibition, 2013. [Photograph by Laura Darcy]

Participants

Authors’ names are listed below alphabetical order. Following each individual’s name is their position at the time of involvement in the After Night project. If participants’ current positions and affiliations are different, they are listed in brackets.

Ashley Bailey: Pre-service teacher candidate, Master of Teaching Program, OISE/University of Toronto. [English Teacher and Guidance Counselor, TMS School, Richmond Hill, Ontario].

Jason Brennan: Teacher, Toronto Catholic District School Board; doctoral student, Department of Curriculum, Teaching & Learning, OISE/University of Toronto; founding member of research team, co-coordinator, Teaching to Learn Project.

Antonino Calarco: Student, Don Bosco Catholic Secondary School; member of youth leadership group, Transfiguration of Our Lord Catholic Church.

Kevin Clarke: Student, Bishop Allan Academy Catholic Secondary School; member of youth leadership group, Transfiguration of Our Lord Catholic Church.

Will Edwards: Teacher, Academic Upgrading, George Brown College; doctoral student, Department of Curriculum, Teaching & Learning, OISE/University of Toronto; founding member of research team, co-coordinator, Teaching to Learn Project.

Catherine Fujiwara: Pre-service teacher candidate, Master of Teaching Program, OISE/University of Toronto. [Teacher, Sacred Heart Catholic High School, Newmarket, ON; Occasional Teacher, York Catholic District School board].

Amir Kalan: Pre-service teacher candidate, Master of Teaching Program, OISE/University of Toronto. [Doctoral student, Department of Curriculum, Teaching & Learning, OISE/University of Toronto].

Julia Kruja: Student, Richview Collegiate Institute; member of youth leadership group, Transfiguration of Our Lord Catholic Church.

Emily McInnes-Greenberg: Pre-service teacher candidate, Master of Teaching Program, OISE/University of Toronto. [English Teacher, Appleby College, Toronto, ON].

Anna Pisecny: Teacher, Riverdale High School, Toronto District School Board; youth group leader, Transfiguration of Our Lord Catholic Church; founding member of research team and co-coordinator, Teaching to Learn Project, OISE/University of Toronto.

Rob Simon: Assistant Professor, Multiliteracies in Education, OISE/University of Toronto; Director, Teaching to Learn Project.

***

PROLOGUE

Speak, you also,

speak as the last,

have your say.

Speak –

But keep yes and no unsplit.

And give your say this meaning:

give it the shade.

– Paul Celan (2001), “Speak, You Also”

Rob: Romanian holocaust survivor and poet Paul Celan experienced the loss of his parents in the Nazi death camps. Through poems like “Speak, You Also,” he paradoxically represented horrors that resisted (and continue to resist) representation. For Celan, surviving, speaking “as the last,” meant writing into and through aporia: confronting his own burning need to write and the insufficiency of what he called “the swell of wandering words” to convey or resolve the indescribable suffering he and others experienced. Celan (2001) despaired that his words were not enough. In the poem “Aureole-Ash,” he wrote: “No one will bear witness for the witness.”

In response to this moral imperative, Jews born after the Holocaust are raised with the phrases never forget and never again. These concepts frame our study of the historical record and are woven into the fabric of stories of loved ones and others who survived or died. The first compels us to remember the atrocities of the past; the second, to ensure that history is not repeated.

Like Celan and Wiesel, my grandmother’s parents died in Auschwitz. My grandmother shared stories of her family’s oppression and her own escape with us, and with audiences in schools and synagogues. Among them was a story of an event that precipitated her parents’ deportation to the camps.

My great grandfather ran a clothing store. In 1937, he was accused of inappropriately “waving to” a Christian woman who had been a customer of his for years, and was jailed. My grandmother was sent to bring her father his shaving kit. As she left the Offenburg jail, she looked up to see her father crying at the bars of a third floor window. It was the first time she saw her father cry, and one of the last times that she saw him alive. As a child hearing this story, and retelling it now, as a parent myself, the image of my grandmother at sixteen, watching her father at the window of his cell, captures the senselessness, profound helplessness, and the consequences of indifference to human suffering.

What is our responsibility as audiences to stories like this? In a speech at the opening of the Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Wiesel (2005) spoke about the character of the messenger in Kafka’s stories who is unable to deliver his message. “We feel sorry for the poor messenger,” Wiesel said, “but there is something more tragic than that. When the messenger has delivered the message and nothing has changed.” Our role, Wiesel reminds us, is not merely to listen to the messages of survivors, but to become the messengers ourselves.

After Night was inspired by this call to be messengers for the messengers. We used art to carry the message of the text forward: a message shaped by thirty educators’ and adolescents’ critical and aesthetic readings, their own personal histories, including in many cases family legacies of forced migration, war, or trauma. Youth and teachers used their feelings of outrage and solidarity with Jews and other victims of intolerance, combined with a sense of what Cornel West (1999) has called audacious hope, to communicate a collective vision of change (figure 1).

ACT 1: The Book

Antonino: Looking back on the After Night project, I think there were many moments when my way of thinking was changed as a direct result of my participation. The most prominent would be my interpretation of the people sentenced to the concentration camps. Before reading Night, I connected the Holocaust to a bunch of statistics, never meant to have any function more than pure numerical information. Night changed this feeling. Wiesel made it clear that there was more to this genocide than facts. He made it possible for me to make the human connection necessary for the generation of emotions. Another part of the book that influenced me greatly was the faith aspect. I am a Roman Catholic who read a book based on the faith struggle of a Jewish boy. I didn’t expect that feature of the book would be one of the most relatable. The challenges Wiesel faced made him ask questions that I could see myself asking or that I have asked. It made me feel included in something larger than myself. As both faiths are monotheistic I knew the feeling of asking God questions in times of weak faith.

Kevin: The experience I had doing this project was astounding. I have not only learned details about a part of history, I have also learned what happens when the mind and body of a human are put to extremes, and that the savage animal nature that we often forget lies beneath our civilized surface. We see this most often in the book in accounts of sons turning on their fathers so that they themselves could survive. Mr. Wiesel himself admits to feeling at times as if his father were a burden. Knowing this, I look closer at the relationships that I have in my life and wonder: What I would do with those people in that situation? Would I be able to hold on to morality? Would they?

After Night has also made me view religion in a different light. At such a young age, Elie loved his religion and wanted to be as immersed in mysticism as he could be. But we see him questioning God and religion more and more as his time in the camps goes on, and his struggles get worse. As a Christian, this spoke to me because the roots of my religion are found in Judaism and many of the rules regarding being devout are similar. Reading Night caused me to ask: How would one keep faith under such excruciating circumstances? How strong would my faith be?

But I also wonder: Did some of those who made it out of the camps become religious? In the face of certain death, did they begin to bargain or pray? I could not begin to try and comprehend the toll of the things so many unfortunate men and women had to go through and the impact this had on a their lives, let alone their faith.

Emily: Our collaborative response to Night involved, first, taking a written text laden with meaning and cutting it up to make something new. This ghastly act of de-stigmatizing the sacred nature of a book and allowing it to become malleable, active, and responsive, allowed us to engage in a deeper reflection about what a piece of writing meant to us. The powerful questions Wiesel poses about the legacy of words, and our dismantling and re-creating of his, allowed us to think about the power of language and memory and community and conversation.

The project demonstrated the power of response, and the insight and engagement that can come with allowing students to respond to their reading and their feelings and thoughts in a creative way beyond the realm of writing.

Anna: As I observed everyone sitting and painting on pages of the memoir, I could not have imagined a better way of personally responding to Elie Wiesel’s (2006) journey and revalidating his experience as one to be remembered and acted on. The memoir and the project left me with great sadness but also with so much hope. This hope was affirmed when Elie Wiesel responded to a letter the youth involved in the project wrote. He emphasized at the end of his letter that we can make a difference in this world and we can enact change. We just need to keep reading and learning. What a better way to enact change than providing individuals with the opportunity to read such a masterful piece?

As a teacher, the After Night project inspired me to integrate Elie Wiesel’s memoir into my curriculum with my Grade 10 students. This year 90 students read Night. They grappled with issues of injustice in our world and are trying to move beyond the hate and sadness in this testimony to enact change and bring the hope that Wiesel emphasizes in his letter. There have been struggles teaching this memoir. Some students are exhibiting some shock that this could have happened, while others are finding it so difficult to read sections that are absorbed with violent act after violent act. Some are very open in responding to the text, while others do not want to speak about it. It has captivated my class in different ways. What more could a teacher want than to invite students to engage with a text that challenges them?

As I keep teaching, there is so much I’d like to change if I have the opportunity to teach Night again. But the one thing that I would not change is what I started with and what came out of the After Night project. It is okay to respond in whatever way you feel comfortable, as long as you act. As all those individuals were painting, we were protesting the silence and giving a voice to all the victims. If my students remember anything, I hope that it is the responsibility to not forget and to keep remembering and acting. Because they can change things, even in small ways.

ACT II: Call for Action

Emily: A book like Night makes me want to do something more upon reading the last page, besides crying. There is a gentle demand that you reflect, discuss, and, for me, create. As an artist I never know when the inspiration will come or what will be the catalyst. Always it stems from some source that has touched my emotions. My instinct after Night was to write, initially. A meandering collection of thoughts, some questions about meaning and trying to find it. That is how I reflect best. But then I am an English teacher who has chosen a career path that involves endless reading and discussing and writing. Not all my students, however, will fit this mould. It is important that students with different styles of expression also have an outlet to reflect, discuss, and create in ways that are meaningful.

There is a beautiful concept in Judaism called Tikkun Olam, which literally means “repairing or healing the world.” It is a belief that the world is fundamentally broken and it is humanity’s shared responsibility to rebuild and transform it. For me, our project was an ethical mitzvoh, an act of kindness or good deed, in our working towards this end. We created a tangible memory to share with our community, and in doing so, patched together one piece of the world. This community connection is part of an essential inquiry schools should be posing to students: How can we make our communities better? My students are given the responsibility to make the world a better place. I support them to create useful evidence of their learning, encourage them to explore their own connections to art and text and life, and find ways to articulate their responses and expressions in ways that are personally meaningful to them.

Kevin: Looking at history helps us, as a society, to ensure our wrongdoings are not repeated, Moreover, it allows us to critically view our successes such as the age of reason and the Enlightenment and pave a path for our future. Writing a letter, making triangles, and even reading Night were all small ways of exploring the past to learn for the future by raising questions like: What makes a good government? How should people conduct themselves in war? What is ethical? But most importantly, how can we educate future generations about these scars on the face of human history? As the survivors of this event grow older and become fewer in number, this question becomes more relevant. It is the job of those who are left after they are gone to answer it.

Rob: Inviting my students to get inside a text (literally and figuratively) through the arts helped them to materialize their readings, develop empathy, and act on it. There is a crucial link between the arts and moral action, what Susan Stinson (1998) describes as “the capacity of the arts to awaken people to the possibility that the world can be different than it is.” This sense of hopefulness and possibility is an indispensable component of critical literacy education. Whether through poetry, painting, or performance, the arts are essential to this process. As Marjorie Siegel (1995) notes, “students need more than words to learn.”

Catherine: Elie Wiesel acknowledges that “appropriate” responses should not be the main objective in reading his book. What is important for teachers and students to take away is the fact that there is a reason why we read Holocaust memoirs, that is, to never forget what happened to the Jews in Nazi Germany and to actively protect humanity from such tragedies happening again. It is everyone’s responsibility to bear witness to such a black mark on our human history.

Amir: Dear Mr. Wiesel,

In 1986, when Saddam Hussein launched his Western-backed missile attack on Tehran, I was thirteen. Saddam usually dropped his European-made missiles on us “infidel Persians” after midnight when I was in bed. When I woke up to the missile alert, I would stick my head into the mattress, shivering and sweating. As soon as the missile hit and I felt sure I was still alive, I thanked God, in tears, for saving my life. I immediately, however, hated myself for thanking God for having someone else killed instead of me. Some people had to perish that night and I found it pathetic to imagine that God, for some reason, had chosen me to survive. I hated myself because I knew I was quietly celebrating someone else’s death, and I hated the universe for having put me in that senseless inhuman position and, at the same time, expecting me to make sound ethical judgments. The war ended, the West decided Saddam was a brutal dictator, and I stopped talking to God forever. Human madness, however, has not ceased to exist—the meaningless lunacy that you, more dramatically than many other people, had to struggle with as a young man.

The Holocaust is one of the most painful examples of how irrationally, and consequently cruelly, human beings could behave. When I read Night, my childhood missile nightmares assailed me again. Following your words in my bed, as well as feeling sad, I was again furious at the barbaric circumstances which had trapped you and your family. It was uncomfortable to read about the metamorphosis of your relationship with the people around you in an attempt to remain human in a beastly inferno. I have a seven-year-old son. All through the book, the only face that I was able to imagine for your character was my son’s face, and I think I do not need to explain how helpless I felt as a father merely by imagining my son in that situation.

I have learned from bitter experience that I, as an individual of average status, can hardly control or impact explosions of human collective madness. I, however, think that I unconsciously decided to become a teacher in order to be ahead of the instant and arbitrary policy making of history's assemblies of fools. When madness hits there is not much time for dialogue and conversation. The boorish take centre stage and the sane are isolated. Teaching has given me the chance to speak with students before tragedies strike and before they have to make decisions that will impact other peoples’ lives. I believe that the experiences of people like you can be a very important part of this conversation and that these stories can bring students of different backgrounds together. Your message can help posterity live in a better world, and, as a teacher, I feel I should do my best to help my students' logic and imagination create a world of love and harmony by learning from people like you—a world whose children feel safer than you and I did.

Thank you for writing Night.

Best Regards,

Amir

ACT III: Creating Art

Rob: As a teacher, I collaborated with art educator and activist Tim Rollins and high school students on an exhibit for the Jewish Museum in San Francisco exploring the concept of Tzedakah – the Hebrew term for “justice.” Rollins’ work with youth in The Bronx—whom he refers to as “Kids of Survival”— involves painting on book pages. The artwork they produce is incredible: Large scale paintings on pages of texts, such as oversized gold and red letter A’s on pages from The Scarlet Letter (Rollins & K.O.S., 1992-1993), or caricatures of world leaders as animals on the pages of Animal Farm (Rollins & K.O.S., 1987). I used this approach as a teacher to engage adolescents who had experienced school failure and violence in their lives.

In his many years supporting teachers to use the arts in schools and teacher education, Jerry Harste (2013) has explored how the arts open up spaces for what he terms abduction. Moving past “the logical conclusion of facts, data, and information,” as Harste put it, arts-based inquiry invites intuition, “the exploration of possibility, creativity, and imagination.”

This idea inspired our use of the arts as a vehicle for critical inquiry in the After Night project. The symbolic and representational power of painting allowed us to address central themes in Wiesel’s text in ways that would not have been possible otherwise. For example, we re-imagined the symbol of a triangle—which Nazis used to designate individuals as undesirable in ghettos and concentrations camps—as a representation of our connections with diverse communities, and our solidarity with victims of injustice, much as activists in the gay rights movement reclaimed the pink triangle as a form of protest and a symbol of pride. Students and teachers painted hundreds of triangles on individual pages of Night—the range of choices they made, in color and design, are incredible (figure 2).

Maxine Greene (1995) has argued that the arts provide “a sense of agency, even of power… [that] can open doors and move persons to transform” (p. 150). In the words of one student who visited the After Night exhibit, the artwork “brings life [and] brightens,” “[teaching] a lesson to those who take the time to view [it]… about what the power of many can accomplish.”

Jason: Contemporary Chinese artist Ai Weiwei claims, “art is a tool to set up new questions” Taken at face value might, this be fairly unremarkable or even obvious. But for Ai Weiwei, who is labeled by his country’s government as a dissident, and by others as “the most powerful figure in contemporary art”—likely saved from censorship only by his fame—this claim represents the radical approach that his artwork takes to set up these new questions. Ai Weiwei’s most famous work is also the most controversial example of how he uses these tools. “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995), depicts Ai Weiwei in a photographic triptych dropping a 2,000-year-old urn, where it shatters at his feet. For some, willful dismantling art ostensibly to make other, new art might be seen as little more than wonton and sensationalized destruction. At its most basic, the potsherds of Ai Weiwei’s photograph might invoke—if not anger or disgust—questions like “is it art?” and perhaps as well “why?”

The largest pieces of the After Night exhibition were five-by-five foot canvases, covered in gesso and, finally, pages torn (or less sensationally, meticulously cut) from Wiesel’s Night. The exhibition also featured smaller pieces that were, inescapably, also cut from copy after copy of Night. Like Ai Weiwei, the art presented in the After Night exhibition might controversially represent a similar kind of destruction of another venerable artefact: the book. The specific genre of book, a Holocaust memoir—likely one of the few modern sacred texts we have—adds sacrilege to our list of misdeeds.

Anna: After Night was my first experience using art as a means to respond to literature. As an individual who has barely picked up a paintbrush, it was a bit overwhelming at first. I wondered how everyone else felt as they were painting. Some seemed serene and others uncomfortable. Some shared their experience of reading Night and others kept silent. However, as I observed everyone sitting and painting on pages of the memoir, I could not have imagined a better way of personally responding to Elie Wiesel’s journey and revalidating his experience as one to be remembered and acted on.

Ashley: Night, which I came to read a second time for this project, produces in me both sorrow and a desire to live. Painting, while I enjoy it, has never produced in me these emotions. Painting has always been Zen-like: a retreat into nothingness. But during this project, the first time I came into the classroom to paint, I was moved by so many emotions. I listened to the students as they tried to make sense of a senseless point in history. I listened to them identify with the character, and I was struck by my own confusion as well.

Catherine: Reflecting on Night, as a part of this project, I discovered that art is a powerful way to respond to texts. Through the communal act of painting triangles on the pages of the memoir, we were able to represent the emotions of Night, in attempt to reclaim the helplessness and regret we felt while reading Elie Wiesel’s experiences as a Holocaust survivor.

In the After Night project, artistic expression was a catalyst for teaching students that when it comes to reading books which detail human tragedy, sometimes it is acceptable and even natural to be without an appropriate academic response. Painting the many triangles we completed as a group has taught me that written and oral responses are not the only way to critically reflect on a text. The medium of painting, an art form, which cannot be contained, easily defined or interpreted, can say more than words. Sometimes, words are not enough.

Ashley: קדיש (Kadish, Hebrew): holy; a Jewish liturgical prayer; a prayer recited by mourners. We covered the words of one survivor of the Holocaust with ashes. We wrote קדיש over the words. We covered over the words—which at that time were to represent the sorrow of loss—to mourn those who did not have the chance to write down their words. How strange that we would rip up a book and cover its words to honour the dead in its pages. Strange that the word we chose was not even in the same language as the text. But when I saw it hanging with the other canvasses—even though I was a part of its creation—I was moved. Yes, קדיש is in many ways the word to represent Night: a text recited by a mourner, a text for the dead, and a text which is holy (figure 3).

Will: “Kaddish,” the Hebrew word for holy, emblazoned in ash, across the pages of Night. We talked about the feasibility of writing with remnants of burnt carbon and we couldn’t decide: Could we write something legible with a liquefied mixture of ash and water? In theory, the idea seemed perfect. The next day Rob brought in a container of ash and few loose shards of charcoal. They came from his fireplace. We set about mixing ash and water on an improvised palate, the grainy solution was inconsistent, some portions congealed into thick globs, while others spread across the canvass in watery grime. We were a little dissatisfied, until we turned to the charcoal and the Hebrew word “Kaddish” began to emerge from the pages of Night.

Ashley: We painted strips of paper to represent our faith. I did two. First I painted blues, yellows, and greens—my faith is my life, my light, and (like blue and green and yellow) all around me. Then, I painted very light strips—barely there strips—as I tried to represent how unperceivable and inexplicable faith can be. I was moved spiritually through text and paint, just as I was moved spiritually through reading Night. As a Christian, I was also moved by experiencing faith with my classmates—whom I know to be of many different faith backgrounds (Muslim, Agnostic, Buddhist, Atheist, Jewish, Hindu, etc.) I was blessed to react collectively and collaboratively to a text I find so personal.

Julia: I gained so much from taking part in this project; growing intellectually, spiritually, and emotionally. I especially feel that I was able to connect with the novel on another level through the art project. By continuously thinking of new colours that reflected the novel, it became that I no longer thought of what I was putting on the paper, I just put what I felt. In my opinion this is a very important step when reading books. It is not only necessary to understand and analyze the book, but also to enjoy it and to enjoy the emotions that come with it.

Will: While I gazed at Jacob’s ladder that evening (figure 4), I recalled another work that Rob and I had read together in the summer of 2011: Slavoj Žižek’s (2008) work On Violence. Žižek draws upon Walter Benjamin’s (1968) “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Benjamin, one of the 20th Century’s greatest philosophers, chose his to take his own life, rather than hand it over to his captors during the Holocaust. In one of his last passages, Benjamin describes a troubling vision that is inspired by Paul Klee’s (1920) painting entitled Angelus Novus, which now hangs in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem:

A Klee painting named “Angelus Novus” shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress (Benjamin, 1968).

The ethical sublimity of this painting can be located in Benjamin’s evocation of the tension between the violence of history and the perpetual yet powerless witness of the angel. The politics surrounding the figure of the witness emerge as haunting tropes in Walter Benjamin’s depiction of history, Elie Wiesel’s testimony in Night, and Paul Celan’s prismatic poetry. Celan’s (2001) quote, which we also discussed in Rob’s graduate seminar, “No one will bear witness for the witness,” is a consonant challenge. I believe the After Night exhibit attempts to address this challenge while thinking through the aporetic (Derrida, 1993) nature of the witness.

ACT IV: Reaching the Public

Ashley: I was curious to see the final product. I forget what the purpose of bringing the Jacob’s Ladder text into the class was. But I remember feeling free at that moment to represent the most deeply personal aspect of myself in front of a whole group of people. And I remember seeing the “ladders” in the art exhibit—the faith portion of the show—and thinking about how completely these different canvasses represented my (our) experience of the text. The “ladders” were just one part of the whole, and producing them allowed me to represent one part of my Night experience (figure 4). Piecing them together with other experiences—of mourning, of outrage, of sorrow, of solidarity—satisfyingly and cathartically represents the complexity of our reaction to the text.

Will: Art is often configured as antithetical to literacy: the former is conceived as an imaginative practice while the latter is often reduced to a didactic process of decoding. In our graduate seminars, we talked about how literacy practices can be framed within the “figured worlds” of institutions (Bartlett & Holland, 2002), some of our questions then evolved: How do we re-configure the worlds of literacy, especially the ones that we see as delimiting for our students?

Defined and delimited possibilities surfaced during the initial stages of thinking through the After Night project while we were looking for a potential venue to host the exhibit. We were given very few options to exhibit the art at OISE—the very institution that brought us together. The idea for the project did not seem to register as either literacy or art that could be posted in a suitable venue at OISE.

Jason: This art exhibition was done by teachers, graduate students, and high-school students from a parish youth group all working in consort to tear, position, gesso, paint, and eventually hang our work publically in one of the most well-trodden paths at the University of Toronto, the Hart House student centre. I am responsible for our public hanging.

On the University of Toronto campus, Hart House is another kind of artefact in and of itself. One of the first dedicated student centres in North America at nearly one hundred years old, Hart House first opened in 1919, and it was constructed throughout the First World War. The adjoining Soldiers’ Tower perhaps best represents that this building was constructed during a time of immense crisis, which it marks with the names of students and alumni of the University of Toronto who died in the First World War (and subsequent conflicts) that are inscribed on its walls.

Hart House itself is emblazoned with artefacts of war as well. On the walls of Great Hall, the site of many important presentations and gatherings over its history, are crests from Universities in the British Commonwealth and allied countries from the First World War, including the University of Pennsylvania. The Hart House Chapel holds the least obvious of these wartime artefacts, however: four pairs of mullioned stained-glass windows. At first glance these seem discordant, depicting no single scene, story, or pictorial representation of anything. That is because these stained-glass windows were reconstituted from shards of glass taken from the husks of destroyed churches in Europe by soldiers who were students from the University of Toronto, and brought back to the University following the war.

Art exhibitions often take place in disinterested galleries, with works hung on plain walls meant to elucidate these temporary residents. Our exhibition was hung in the main corridor of Hart House, precariously perched on nylon cables stretching from the ceiling (Figures 1 & 3). This also positioned our exhibition as something interested in its surroundings, made different by being placed as it was: not in a sterilized gallery, but in the heart of a university campus. In this way, Hart House was not the first choice for an art exhibition—but it was the best choice.

Positioning fragments of books with fragments of stained glass allows for different kinds of questions to be asked about both, their relation to their very different testimonies of conflict, their relation to the building in which they are in, and, broadly, how and where art is encountered in our lives. Classrooms, for example, present spaces where art is often constrained to certain discrete lessons, if it is present at all, and where books are predictably read and returned, saved for the next day’s lesson or next year’s students. On the other hand, artistic responses to a book—where students are invited to interact with books as physical, cultural artefacts in different, potentially counter-discursive ways—invoke intrinsically different questions & meanings than reading a book and writing about it. This positions art in, and in conversation with, classrooms; to ask new questions of the spaces and the stories we encounter.

What kinds of stories can be told and retold from fragments of pottery, glass, and paper? Who has license or obligation to tell these stories? Who has a right to listen? How can we encounter cultural, historical, or social artefacts in our own time, under duress of expectation, policy, or curriculum? And in what ways might these questions intersect or interrupt the predictable discourses of our lives?

EPILOGUE

Julia: Working on the After Night Project over the course of the past two years has definitely been a worthwhile experience. Not only did I gain much insight on the Holocaust and the other happenings of World War II, but I was also able to share and communicate my thoughts on such a significant historical event with others. Although there have been many activities done in preparation for this project, the most memorable one would have to be the letter that we wrote to Elie Wiesel. When studying World War II, or any historical event, we always look at the hard facts and at things that happened in the past. Being able to analyze Professor Wiesel’s account of the Holocaust also helped to go past the basic facts that we learn in class. However, with this letter we focused more on the present than the past. With Professor Wiesel having an actual memory of the War, it becomes not so much a story, but something real, something that, for me, is almost impossible to picture. As opposed to learning the impacts and effects on the entire population, we learned how one single person was impacted and affected. To know exactly how one life was shattered and destroyed helped to paint a picture of the extent of the damage, intensifying any emotions that might surface when remembering the Second World War.

Art is considered to be the best way to express your feelings and thoughts, and in this case it rang true. By choosing colours that represented themes in the novel, it was easier to connect with the emotions that were portrayed by Wiesel in his work. After completing this project, I came to the realization that I would never truly be able to recognize exactly what happened in the Second World War because I was not there to experience it firsthand. The pain, the suffering, and the fear are all emotions that I will never, as a result of the War, feel. Even though I was unable to achieve the unachievable, I did grow a deeper understanding of the nature of man, what drives us and gives of courage, and what weakens us.

Catherine: Participating in the After Night project was a memorable experience, heightened by the different communities that were present within the room. Graduate students, teacher candidates and high school students all painted alongside our professor, Rob Simon, letting our paintbrushes and colour choices do the talking for us. I recall trying to select bright pastel colours—colours I associate with happiness—as a means of fighting against the horrors inflicted on the Jewish people by the Nazis. In a similar vein to using the upright triangle, I wanted to reclaim the colourful and bright triangle to oppose the evil dark hues I align with Nazi Germany through my colour choices.

Ashley: I sat down to paint with a couple of the students. We were painting triangles—tasked with finding a colour which represented our reaction to the text. My colour was yellow: the most difficult colour for the eye to perceive. We all painted our triangles with care. As the students processed through paint, both of the boys who sat with me made variations of brown. Brown was not their intent. Instead, they felt a mixture of feelings, so they painted with a mixture of colours. Brown: muddled, muddy, messy, earthy, dirty. How do we pull apart everything we feel when we listen to a story of death and faith and outrage and sorrow? Well these students didn’t. While I painted yellow triangle after yellow triangle these boys painted brown after brown, after brown. Eventually, I painted an orange triangle, settling on my feeling of outrage—bold, unquenchable. I was outraged at the inability to express in words how I felt reading Night, outraged that such a degree of evil was able to exist, and outraged that I had some pleasure in reading the memory of it—the words are so beautiful, the empathy so immediate. As we painted, the boys became frustrated with their unintentional browns. They started to separate the colours after that: red for rage, green for life, purple for mourning. But I remained outraged.

Jason: Collaborative art, like collaborative writing, has almost always been framed like an oxymoron to me. As someone with a humanities background, art and writing are often represented in undergraduate degrees as solitary, enchanted projects carried out by nearly mystical people—usually men—and delivered to the world without much of a trace of the process. This is certainly a naïve view of literature and art, but it captures the emphasis of a degree in English literature, and unfortunately mirrors my own experiences with my degree and assigned writing, those single-authored papers that inevitably show up in every single university course. Doctoral work in particular has been the most notable casualty of this view that casts writing as solitary. I can’t recall the number of times I have heard a Ph.D. being compared to a monkish lifestyle, where a student sits in a cramped library cubicle, ostensibly reading and writing for five years.

The After Night project was a way out from this reductive and predictable rhythm of art and writing, and a way in to a more nuanced and fruitful experience as a doctoral student. After Night not only challenged notions of solitary work, it lived those challenges and bore them out on an almost daily basis. I have said before to other audiences that I never thought, as a doctoral student, I would have spent any of my time painting with youth and teachers, or contacting galleries for an exhibition. In truth, perhaps I bought into some of the received wisdom about doctoral work, if only because I had no recourse or example of an alternative view.

Anna: I’ve never seen the students in my youth group as students. I’ve always seen them as fellow members of my faith community. Members that have a unique bond but also a unique identity that is shared amongst the community. Working with these youth in the After Night project has changed the way I view myself as a teacher and how I interact with my students. In their letter to Elie Wiesel, students asked what Wiesel’s relationship with God was like after his experience during the Holocaust. How could one have a relationship with God after all of this? What kind of a God would allow this to happen?

In his response, Wiesel remarked that his faith is “a wounded faith.” This statement is something that the students reacted to and discussed as we shared a reading of the letter together and debriefed our reactions. We shared parts of our identity and explored personal beliefs, furthering our bond as a community.

When I step into my classroom, I strive to create a community like this. After this experience I have found that it is now impossible to separate my identity as a person of faith, as a woman, as a sister, as a daughter, as a friend, as a leader, and as a teacher. They all make up who I am and I bring this into my teaching in the hope that my students also feel safe to explore their own identities, to explore who we are as we read, through the experiences of others in the texts we share.

Rob: As an educator, After Night has raised questions for me, among them: How can the arts address inexpressible events like the Holocaust? In what ways might the process of cutting and painting on pages from Night have memorialized or trivialized trauma? What insights has this project evoked (and continued to evoke) for participating teachers and youth, or for viewers? What, ultimately, are the impacts of this work?

These and other questions suggest that the process of responding to texts like Night is always unfinished. In the spirit of Elie Wiesel (2006), who wrote of his personal obligation to bear witness to the horrors of the Holocaust and the limitations of language to do so, it probably should be.

***

“I only know that without this testimony, my life as a writer—or my life, period—would not have become what it is: that of a witness who believes he has a moral obligation to prevent the enemy from enjoying one last victory by allowing his crimes to be erased from human memory.”

– Elie Wiesel (2006), from the Prologue to Night

Emily: We hear you.

We want to be part of this testimony; this effort to remember and ensure that no one forgets. Through us we sustain Jewish religion, Jewish culture, Jewish tradition, and Jewish memory, but also all religion, all culture, all tradition, and all memory.

However ugly, it is our obligation to reveal evil whenever we see it and force a conversation about it. Evil doesn’t go away when we bury it.

When language burdens our memory, it is possible to reach a semblance of our notions through art. We turned to painting, and re-incorporated your words to invent a new language that surpassed language, full of colour and emotion, individual and collective loss and remembrance.

We try to understand, and we also recognize our limitations to understanding. This fine balance we try to walk, and make meaningful.

Your words have done both, as well as pleasure, warmth, disgust, hatred, disbelief, uncertainty, anguish, faith.

We try to find a way to take responsibility for passing along your words as witness. We can take responsibility for ourselves. That is the easy part. We create a tangible memorial to try to encourage others to take responsibility for passing along the message: that we know what happened. That what happened is both over-flowing with meaning, and desperately lacking it.

Authors’ Note

Support for this project was provided by a grant from the Connaught Fund. Our gratitude to Gerald Campano and Nancy Hornberger for their invitation to participate in the Ethnography in Education Research Forum, to Charles Washington, Holly Link, Hoa Nguyen, and Debora Broderick for their help with the event, and to Susan Lytle and Vivian Vasquez for organizing an affecting collective response. Appreciation as well to Tim Rollins and Kids of Survival for their artistic and pedagogical inspiration. Finally, a special note of thanks to Professor Elie Wiesel, for writing a text that moved and inspired us, and for his thoughtful reply to our letters.

Several participants have family members who survived or perished in the Nazi death camps: Fannie and Jacob Maier; Kaethe Ritter; Walter Simon; and Rudy and Gretel Simon. This article is dedicated to their memory.

Bartlett, L., & Holland, D. (2002). Theorizing the space of literacy practices. Ways of Knowing Journal 2(1), 10-22.

Benjamin, W. (1968). “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations (H. Arendt, Ed.). New York, NY: Shoken Books Inc.

Berry, T. (2009). Tim Rollins and K.O.S.: A history. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Celan, P. (2001). Selected poems and prose of Paul Celan, (J. Felstiner, trans.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Derrida, J. (1993). Aporias. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Eisenstein, P. (2003). Traumatic encounters: Holocaust representation and the Hegelian subject. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Harste, J. (2013). “Transmediation: What art affords our understanding of literacy.” Oscar Causey Address at 2013 Literacy Research Association Convention.

LaCapra, D. (1996). Representing the Holocaust: History, theory, trauma. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

LaCapra, D. (2004). History in transit: Experience, identity, critical theory. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Siegel, M. (1995). More than words: The generative power of transmediation for learning. Canadian Journal of Education, 20(4), 455-475.

Simon, R., Brennan, J., Bresba, S., DeAngelis, S., Edwards, W., Jung, H., & Pisecny, A. (2014). Investigating literature through intergenerational inquiry. In H. Pleasants & D. Salter (Eds.), Community-based multiliteracies and digital media projects: Questioning assumptions and exploring realities. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Simon, R., Campano, G., Broderick, D., & Pantoja, A. (2012). Practitioner research and literacy studies: Toward more dialogic methodologies. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 11(2) July 2012, 5-24. Retrieved from: http://edlinked.soe.waikato.ac.nz/research/files/etpc/files/2012v11n2art...

Stinson, S. W. (1998). Maxine Greene and arts education. In W.F. Pinar (Ed.), Passionate mind of Maxine Greene: I am.... not yet. London, UK: Falmer Press.

West, C. (1999). The Cornel West reader. New York, NY: Basic Sivitas Books.

Wiesel, E. (2005). Speech at the opening ceremony of Yad Vashem. March 15, 2005.

Wiesel, E. (2006). Night. Revised edition. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

Wiesel, E. (2012). Remarks on receipt of the 2012 Lyndon Baines Johnson Moral Courage Award. Retrieved from https://www.hmh.org/au_Wiesel_remarks_2012.shtml.

Žižek, S. (2008). Violence: Six sideways reflections. New York, NY: Picador.

Artwork

Chagall, M. (1973). Jacob’s Ladder [Painting]. Saint-paul-de-vence, France: Private collection.

Klee, P. (1920). Angelus Novus [Painting]. Jerusalem: Israel Museum.

Rollins, T. & K.O.S. (1987). From The Animal Farm (After George Orwell) [Painting]. Zurich, Germany: Gallery Eva Presenhuber.

Rollins, T. & K. O. S. (1992-1993). The Scarlet Letter—The Prison Door (After Nathaniel Hawthorne) [Painting]. Washington University, St. Louis, MO: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum.

Weiwei, A. (1995). Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn [Photograph]. USA: Private collection.