Integrating Aesthetic Education to Nurture Literacy Development

The focus of this paper is the preparation of alternative route to certification candidates (ARC) for the elementary school classroom. One of the important dispositions of an ARC teacher in the urban elementary classroom is the ability to understand the culture of the family, school and community surrounding the children. This article demonstrates one approach that may be designed for integration into the teacher preparation sequence to address this need. The method used in this article integrated aesthetic education into teacher preparation through a collaboration between Lehman College, CUNY and the Lincoln Center Institute. This paper details one unit designed for use in the English Language Arts (ELA) classroom that integrates aesthetic education to nurture literacy development.

In 2000 Lehman College, City University of New York, initiated a relationship with Lincoln Center Institute (LCI), the educational branch of Lincoln Center in New York City, to integrate aesthetic education into their classrooms during a time of severe budget cuts to arts programs. The understanding of aesthetic education in the partnership is based on the definition proposed by Maxine Greene (2001):

“Aesthetic education,” then, is an intentional undertaking designed to nurture appreciative, reflective, cultural, participatory engagements with the arts by enabling learners to notice what is there to be noticed, and to lend works of art their lives in such a way that they can achieve them as variously meaningful. When this happens, new connections are made in experience: new patterns are formed, new vistas opened. Persons see differently, resonate differently (p. 6).

The collaboration between Lehman College and LCI aimed to develop a disposition toward aesthetic education within pre-service and in-service teachers. The philosophy was rooted in the premise that if pre-service and in-service teachers experienced a strong model of integrated aesthetic education during their graduate studies, they could translate this to integrating the arts in their own classrooms.

Lincoln Center Institute, founded in 1975, is a leader in the integration of aesthetic education in New York City as well as globally. LCI develops programs that include the visual arts, dance, music, theater, storytelling, and architecture as forms of aesthetic education experiences. LCI liaisons, or teaching artists, are the cornerstone of the LCI relationship with Lehman College. Teaching artists are professional artists trained by LCI who work with school and college faculty to integrate the arts. LCI is a visible presence in public schools, from preschools to high schools, and colleges throughout New York City. LCI’s research on arts and education is detailed on their website at www.lcinstitute.org

This paper details the model of aesthetic education developed by LCI and the Graduate Childhood Education Program. Lehman College, based in the Bronx, is challenged to recruit and prepare individuals to work in urban elementary school classrooms. While recruiting and sustaining highly effective candidates is a challenge for the entire public school community, urban school districts bear a large part of the burden. According to Duncan (2009), “Children today in our neediest schools are likely to have the least qualified teachers. And that’s why great teaching is about so much more than education. It is absolutely a daily fight for social justice” (para. 7). Alternative Route to Certification (ARC) programs such as the New York City Teaching Fellows program focus on the recruitment of highly effective teachers into hard-to-staff schools.

The New York City Teaching Fellows program is administered by the New York City Department of Education. The Fellows program was created in 2000 to recruit individuals seeking a career change to teach in low-performing schools within New York City’s five boroughs. While the ARC programs are responsible for the recruitment of highly qualified candidates, institutes of higher education (IHE) are responsible for preparing these candidates to enter public school classrooms. Often times ARC candidates do not grow up in the high–needs, urban neighborhoods in which they teach. One of the most important dispositions of an ARC teacher in the urban elementary classroom is the ability to understand the culture of the family, school, and community surrounding the children. Understanding the complexity of the child’s world is important to nurturing their social, cognitive, and emotional development in the classroom.

The author has been the program coordinator of the Graduate Childhood Education Program at Lehman College, CUNY since 2006 and has collected data on aesthetic education for the past eight years as a coordinator and instructor. This article demonstrates one approach to integrated aesthetic education developed by the Graduate Childhood Education Program in the course Family, School, and Community. This paper details one unit of the course designed to integrate aesthetic education and nurture literacy development in the English Language Arts (ELA) classroom. The unit models the integration of LCI’s Capacities of Imaginative Learning into a teacher preparation program.

Build a Culture of Caring

There is a need to create caring teacher preparation programs to form caring practitioners in the classroom (McNamee, Mercurio & Peloso, 2007; Goldstein & Lake, 2003). These programs are an essential component of nurturing developing elementary school teachers to “think, feel, and behave care-fully” (McNamee, Mercurio & Peloso, 2007, p. 281). A classroom community is not solely a sequence of academic activities, but the foundation for a student’s way of being in their family, school, and community. A culture of caring helps to build a community of interdependence in all of these areas (Levine, 2009). To enact this approach for the New York City Teaching Fellows, they needed to be immersed in a culture of caring during their graduate courses in order to embody these practices for their own classrooms.

Noddings (1992) asserts that it is imperative to incorporate themes of care into our PK-12 curricula to: expand students’ cultural literacy, help connect standard subjects, connect our students and our subjects to great existential questions, and create person-to-person connections. A caring academic environment nurtures democratic and socially just relationships among families, schools, and communities and enhances student success. Teachers who establish a network of support enhance the social, emotional, and cognitive growth of their students. The culture of caring concept must integrate an understanding of a student’s family, school, and community in order to nurture students.

Living Literacy

One important aspect of building a community of caring is for a teacher to understand where his or her students hail from. A teacher needs to be aware that “young people’s literate identities both mediate, and are mediated by, the social worlds in which they live” (Alvermann, Jonas, Steele, & Washington, 2006, p. xxv). As students enter the classroom, their living literacy is evidenced by the literate currency they embody. Living literacy includes “the ways in which … people read and write their lives” (Neilsen, 1989, p. 2), while literate currency is “the multiple and interactive forms of literacy that students bring into the classroom … literate currency is also gleaned through their personal, familial, and social interactions, both within and outside of schools” (Obidah & Marsh, 2006, p. 107). The elementary school ELA teacher has the ability to empower students by creating spaces in the classroom where literacy, in its multiple forms, can be nurtured in the context of a caring community.

To support this culture of caring model in the elementary ELA classroom, research-based practices concerning the living literacy of developing human beings must be implemented (Neilsen, 1989; Neilsen, 1998; Washor, Mojkowski, & Foster, 2009). This recognition of the “powerful interchange between young people’s experiences in the world and what they read. …The cycle of experience and reading—a cycle of life to text and text to life—is at the heart of literacy and learning” (Washor et al., 2009, p. 521). As candidates pursuing an alternative route to certification to teach in hard-to-staff schools, it was imperative that NYC Teaching Fellows understood the living literacy of their students and the literate currency they carried into the classroom.

Integrating Aesthetic Education

Lehman College developed a method of integrating aesthetic education through their partnership with LCI. The following unit integrated aesthetic education to nurture literacy development among the Fellows and connected these methods to their own pedagogical foundation. The vision for the unit was based on the Capacities for Imaginative Learning framework developed by LCI (2007, 2009):

• First Capacity: Noticing Deeply

• Second Capacity: Embodying

• Third Capacity: Questioning

• Fourth Capacity: Making Connections

• Fifth Capacity: Identifying Patterns

• Sixth Capacity: Exhibiting Empathy

• Seventh Capacity: Living with Ambiguity

• Eighth Capacity: Creating Meaning

• Ninth Capacity: Taking Action

• Tenth Capacity: Reflecting/Assessing

The Capacities for Imaginative Learning were used as the guiding framework for developing the unit and evaluating student work.

The activities in this unit are structured to build a culture of caring among a diverse group of students in the ELA classroom. Although many different pedagogical theories are incorporated into this unit, Baines and Kunkel’s (2000, 2003) philosophy of establishing a writing environment that nurtures human connection is the foundation. It is impossible to document all that occurred in the unit within the parameters of this article; however, what follows is a sample of activities that illustrate the application of each of the Capacities.

First Capacity: Noticing deeply. The first Capacity for Imaginative Learning is noticing deeply. To notice deeply is “to identify and articulate layers of detail in a work of art or other object of study through continuous interaction with it over time” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). This unit introduced the concept of noticing deeply through the work of art entitled Tar Beach by Faith Ringgold (1988). Tar Beach is described by the Guggenheim collection as an “acrylic on canvas bordered with printed, painted, quilted, and pieced cloth” (Ringgold, 1988).

For this activity, the Fellows convened in writing groups of four students each. The image of Tar Beach was distributed and each group was asked to answer the following question in their writing journals: What do you notice? The question asked the Fellows to “observe or notice anything and everything about the picture, from the lines, shapes, and colors to the images themselves and how they are arranged on the page in relation to each other” (Zakin & McNamee, 2009a, p. 32). After reflection, the students shared their noticing with their writing group. The following is an excerpt from one Fellow’s journal:

The quilt is dark in the middle with bright colors around the border but the children on the mattress are also bright, the watermelon is bright. The image is full of square shapes like quilting squares – but the squares are at different angles to each other. Squares of quilt on the border, square of mattress, square/rectangular buildings in background, square of rooftop, square of table where adults are eating and food is sitting.

The children are lying close to each other on the mattress. They are next to the adults at the table but not involved with them. There are words on the top and bottom of the quilt. The children are surrounded by the bright colors in the quilt border. Pinks, reds, deep blue sky. City lights in the distance and in the sky. The girl is flying in the sky.

Fellows also answered the following question in their journals: What is going on in the picture? The second question invited the Fellows to make some sense of Tar Beach (Zakin & McNamee, 2009a). Once again, the Fellows shared their responses with their writing group. The following are excerpts from two Fellows’ writing journals:

I feel that the girl and boy are close – probably siblings and they are imagining the sky together. Their eyes are looking to the side – perhaps to the girl flying. Maybe she represents their dreams? This looks like a very comfortable family to be part of. The men and women at the table lean into each other and the children lean into each other. They seem close and loving…and the border of the quilt also ties them altogether into a close and warm square.

There is a sense of peace about the quilt. The stars in the sky and the party on the roof seem to contradict the usual hustle and bustle of the city surrounding them. It is as if they have created their own peaceful spot on top of the city. The flying girl (is it the girl on the mattress?) is also peacefully gliding through the night sky. And the boy and girl lying down are also lying very still. Even though the quilted border is very busy with different colors it is also peaceful in its own way…It provides a soft frame (but maybe that is just me assuming that it is a soft cotton fabric?) to the peaceful dinner party.

Following this exercise, the writing groups engaged in a large group discussion to share their responses. The important skill of noticing deeply is “to identify and articulate layers of detail” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). During the large group discussion, the Fellows remarked at the levels of detail they were able to discover with the help of their colleagues in the smaller writing groups. The connection was then transferred from deeply noticing a work of art to the complexity of one student.

Second Capacity: Embodying. The second Capacity for Imaginative Learning is embodying. Embodying is the ability “to experience a work of art or other object of study through your senses, as well as emotionally, and also to physically represent that experience” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). To nurture the development of the second capacity, the students created an artistic representation of their hometown or a place on the globe that they associated with the word “home.” A variety of art materials were available to the students to complete the hometown artistic pieces.

Once the Fellows completed their design, they shared the piece within their writing groups as they had done for the Tar Beach activity described in the first capacity. Once complete, the collages were exhibited for each member of the writing group to notice deeply, and members of the group took turns presenting their collages. The artist would not comment, but other members of the group were encouraged to notice deeply and express their observations of the artist’s collage. The following is an excerpt from a journal entry answering the question: “What do you notice?”

The colors are bright at the top right corner: yellow, orange, light blue. The colors at the bottom are darker: deep reds, dark purple, navy blue. The bottom contains heavy objects: buttons, craft sticks, dried pasta. Materials are all tangled together. The top right has light materials – tissue paper, feathers.

The Fellows wrote observations in note form to the artist for the second question: “What is going on here?” As this is a personal exchange, the notes allowed the Fellows to comment on each other’s work through the written word instead of a public arena. The following is an example of a letter from the same individual quoted above:

Dear J,

Thank you for sharing your collage with me. I notice the use of dark colors and heavy materials at the bottom of your piece. The materials are all jumbled together and there is a feeling of entanglement. I am torn between two interpretations: One could be the heavy, strong foundation of your home built upon so many sturdy objects. But perhaps (because of the dark colors?) a sense of dark, heaviness associated with home? This is a huge contrast to the use of bright colors and light materials in the upper right. There is a sense of freedom in this corner. The transparency of the tissue paper mimics a stained glass window where light pours in. A deep contrast to the bottom. Perhaps demonstrating the “baggage” we all bring and yet it allows us to become beacons of light?

Thank you,

S.

The Fellows were asked to create a work of art to demonstrate their embodiment of the material, the key aspect of the second Capacity for Imaginative Learning. By creating their own collage of home, the Fellows were able to explore and share their own embodied living literacy.

Third Capacity: Questioning. The third Capacity for Imaginative Learning is questioning. Questioning is the ability “to ask questions throughout your explorations that further your own learning; to ask the question, ‘What if?’” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). The Fellows each assigned an adjective to the piece Tar Beach and wrote a vignette making some sense of the image. They remained in their writing groups for the creation and editing of the vignettes, developing rough drafts through peer critiquing and peer revision i(Baines & Kunkel, 2003). The following is an example of a vignette:

PEACEFUL

The sleepy rooftop was a haven for all those seeking a respite for their troubles. You went there to get away from the struggle and strife of the world. Its citizens coexisted in a peaceful manner. So relaxing and restful was it that humanity flocked there in droves knowing that the mellifluous babbling of the city below would lull them into blissful, sleepy, peaceful dreamland! A tiny beach sheltered in the city, waiting to be enjoyed by all who need a respite from the frantic pace of life below.

This activity allowed the Fellows to try to interpret the lives of the people in Tar Beach by the data they collected by answering the questions, “What did you notice?” and “What is going on in this picture?” Each vignette was read to the entire class by the group. There was a large group discussion about the importance of being care-ful (McNamee, Mercurio & Peloso, 2007) when trying to interpret someone’s life story. The importance of questioning the life stories of each Fellow and the impact this may have on one’s dispositions as a teacher was reinforced: What can someone else’s story (even if very different) teach us about our own lives? As teachers, it is a difficult task to interpret the life of a child by the credible signs they demonstrate. This activity helped the Fellows develop the skills necessary to question the literate currency the elementary school children carry into the classroom. At the end of the activity, the children’s book Tar Beach (Ringgold, 1991), based on the Ringgold story quilt, was read.

Fourth Capacity: Identifying patterns. The fourth Capacity for Imaginative Learning is identifying patterns. Identifying patterns is the ability “to find relationships among the details that you notice, group them, and recognize patterns” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). For this activity, a large world map and a local map of New York City were hung on a bulletin board. The Fellows chose different push pins to designate different locations on the globe that have meaning in their life story. For instance: Red push pins indicate where a student was born, blue push pins indicate different locations a student has lived along his/her journey, and yellow push pins indicate where a student currently lives. Individuals also chose to place a pin on a place that had significance to their life narrative even though they have never lived there. For example, one woman placed a pin on Jamaica even though she had never lived there because her family emigrated from Jamaica and the culture plays an important role in her living literacy. The completed maps display the impact of geographic location on the living literacy of each student in the class.

Using the maps, students explored the importance of home in a global society. The life story of each member in the class provided a foundation for the Fellows to discuss the implications these stories have on an idea of home. The Fellows began to define the concept of home and imagine what home means to people from different parts of the globe. On a local level, the conversation explored the idea of home for elementary students through a variety of questions, for example: Where is home? What languages are spoken at home? Who lives at home? Do you consider where you currently live home?

Fifth Capacity: Making connections. The fifth Capacity for Imaginative Learning is making connections. Making connections is the ability “to connect what you notice and the patterns you see to your prior knowledge and experiences, to others’ knowledge and experiences, and to text and multimedia resources” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). For the next step of the unit, students created poems of their hometown or a place on the globe they associated with the word “home.” Since the process of writing poetry can be intimidating, the previous activities were integrated to allow the Fellows access to the emotions required to complete this exercise. This approach is based on Baines and Kunkel (2000) advocating for “using off-beat strategies, competitive games, interdisciplinary hooks, art and multimedia, and indirect approaches to teaching some of the difficult lessons of writing” (p. xii).

The Fellows were asked to write a poem using Baines’ (2000) activity “Performance Art Poetry” (Baines, 2000, p. 33). Using the following prompt, students were asked to write a poem about what they consider to be their hometown.

Hometown

Place where you grew up and a verb (2 words)

The landscape (4 words)

Smell or taste of your hometown (6 words)

Music, song, or sounds that remind you of your hometown (8 words)

Kind of people who live there (10 words)

An important event in your life (12 words)

An important event in your life (12 words –you can repeat the above line or write a new one)

A dream or nightmare (10 words)

An influential person (8 words)

The specific advice or truth someone once gave you (perhaps you heard it from the person mentioned above). Try to write out their advice specifically, then delete the quotation marks (6 words)

The weather (4 words)

The following is an example of a final draft of a hometown poem.

Harlem

Harlem swings

Music, streets, games, children

Fried chicken, collard greens, hot peppers

Bongos, congas, soul, calypso, jazz, street-corner harmony

‘Bamas, Geechees, ‘Ricans, Jamaicans, artists, musicians, winos, junkies,

morticians, seamstresses

I went to Jamaica to visit my grandmother, my aunt and cousins

The summer after I graduated from elementary school PS 28 in Harlem

I often dream I am back in school once again

Mrs. Washington, my fifth grade teacher, taught me

All people are the same inside

Hot summers, frigid winters

Colorful Harlem.

Sixth Capacity: Exhibiting empathy. The sixth Capacity of Imaginative Learning is exhibiting empathy. Exhibiting empathy is the ability “to respect the diverse perspectives of others in the community; to understand the experiences of others emotionally, as well as intellectually” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). An important aspect of constructing a caring community is exhibiting empathy, and as teachers, it was necessary for the Fellows to learn to help others voice their living literacy by exhibiting empathy. As mentioned above, Fellows developed rough drafts of their hometown poems through peer critiquing and peer revision in their writing groups (Baines and Kunkel, 2003). The Fellows met in writing groups and shared initial drafts of their poems, using the skills developed through the first five capacities in the editing process.

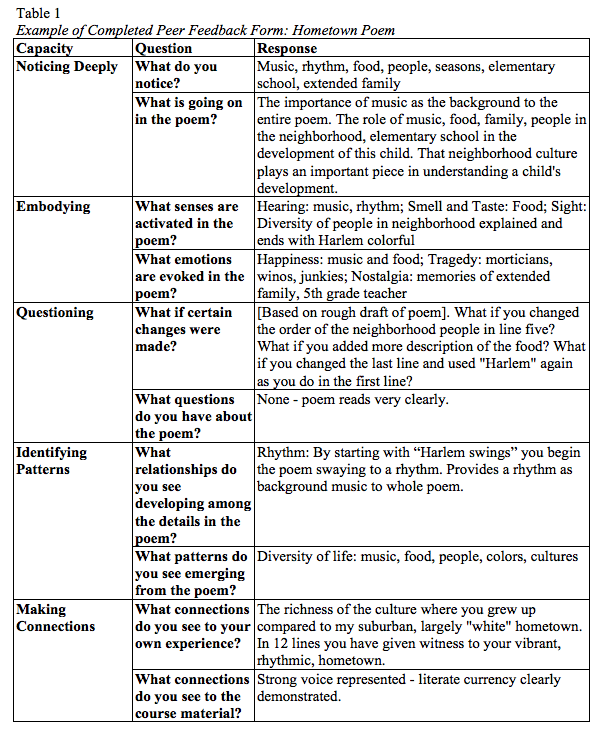

A handout was developed to guide the Fellows through the editing process. Each Fellow read his or her poem and shared a copy of the poem with other members of the group. For homework, the Fellows completed the Peer Feedback Form shown in Table 1 for each poem. The poems were read the following day, and the group discussed the feedback provided by each member of the group. The following is an example of a completed feedback form for the rough draft of the hometown poem “Harlem” shared previously.

The group editing process allowed the Fellows to “understand the experiences of others emotionally, as well as intellectually” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). As editors, the Fellows were actively listening to and hearing the stories of their colleagues emotionally and intellectually. This allowed each individual to share his or her story and receive feedback to nurture their own living literacy. It also gave each Fellow an opportunity to hear the voices of others and find authentic means of evaluation to validate the shared story.

Seventh Capacity: Living with ambiguity. The seventh Capacity for Imaginative Learning is living with ambiguity. Living with ambiguity is the ability of human beings “to understand that issues have more than one interpretation, that not all problems have immediate or clear cut solutions, and to be patient while a resolution becomes clear” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). For this unit, a professional storyteller was invited to share his craft with the Fellows. The storyteller shared personal stories and folktales that demonstrated a variety of forms of living literacy. The storyteller used an array of narrative forms to give insight into identity-making processes throughout our oral tradition. The importance of listening to and hearing the stories of others was discussed as an essential skill in discovering the literate currency of individuals. Integrating a professional storyteller from the surrounding community into the ELA curriculum invited an outside member of the neighborhood to become involved in the education of elementary students in a foundational way.

The partnership between Lehman College and the Lincoln Center Institute allows teaching artists to work with college faculty. This partnership allows the teaching artists’ aesthetic education expertise to be woven into the existing content required in the college course. During the semester, a teaching artist is assigned to work individually with faculty to plan an aesthetic education experience. In this instance the teaching artist prepared the NYC Teaching Fellows for a the performance by the storyteller. The aesthetic experiences vary each semester including but not limited to: dance, music, theater, architecture, and the visual arts. The teaching artist and faculty member plan and implement an aesthetic education lesson into the existing teacher preparation courses.

Eighth Capacity: Creating meaning. The eighth Capacity for Imaginative Learning is creating meaning. Creating meaning is the ability “to create your own interpretations based on the previous capacities, see these in the light of others in the community, create a synthesis, and express it in your own voice” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). In order to prepare the Fellows for a future reading of their hometown poems, they were introduced to a storytelling workshop (Gangi, 2004). Through a series of sequenced activities, the Fellows learned to express their poems through the art of storytelling and developed a personal story about a time they got into trouble as a child (Gangi, 2004).

After the performance of each Fellow’s childhood trouble story, the larger group convened for a discussion on discourse following Gee’s (2004) model. The Fellows explored the small “d” discourse, or the language, used in the stories. The large group discussion encouraged the Fellows to notice deeply and see beyond the small “d” for the capital “D” Discourse, which includes people, places, objects, tools, technologies, and ways of speaking, listening, writing, reading, feeling, valuing and believing that were evident in the stories (Gee, 2004). As an elementary school ELA teacher, it is essential to understand that human discourse is the foundation for giving voice to a student’s literate currency. By providing the skills of storytelling, this course empowered the Fellows to give voice to their own literate currency and the tools to express their living literacy.

Ninth Capacity: Taking action. The ninth Capacity for Imaginative Learning is taking action. Taking action is the ability “to try out new ideas, behaviors or situations, in ways that are neither too easy, nor too dangerous or difficult, based on the synthesis of what you have learned in your explorations” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). To complete the unit, the Fellows organized a poetry reading or poetry “slam” of their hometown poems. An important aspect of this unit was empowering the Fellows to give voice to their living literacy and experience how the praise a student receives after a public reading is beneficial to literacy development (Baines & Kunkel, 2003). In an elementary school environment, organizing an evening poetry reading would enable different members of the community to participate in the celebration.

Tenth Capacity: Reflecting/assessing. The tenth Capacity for Imaginative Learning is reflecting/assessing. Reflecting and assessing are the ability “to look back on your learning, continually assess what you have learned, assess/identify what challenges remain, and assess/identify what further learning needs to happen” (LCI, 2007, 2009, p. 3). For the final requirement of the unit, students were asked to create a book to publish their hometown poems. The Fellows worked together to design the book and construct a table of contents and cover. This final activity allowed the Fellows an opportunity to reflect on the entire unit and construct a meaningful order for the poems using the skills of the ten Capacities for Imaginative Learning. In order to assess their own learning, the Fellows also reflected on their own performance throughout the unit by completing the Capacities Rubric found in Table 2 (Zakin & McNamee, 2009b). This rubric is specifically designed to assess the Capacities for Imaginative Learning.

Final Thoughts

The preparation of an ARC candidate for the urban classroom must include an understanding of the culture of the family, school, and community surrounding the elementary school children. The elementary school ELA teacher has the opportunity to create a caring environment that allows students to explore their living literacy, validates the literate currency of each child, and provides a caring space for children to nurture their own voice. The life-to-text and text-to-life cycle (Washor et al., 2009) allows children to develop the skills to integrate their own living literacy with the ELA curriculum. Aesthetic education offers a pedagogical foundation to foster a connection among individuals within the context of a language arts classroom. The Capacities for Imaginative Learning provide a developmental framework to structure the integration of aesthetic education in a classroom environment by creating a framework that establishes a culture of caring in an education setting. Through the model of aesthetic education explained here, students are able to explore their own literacy development through the lens of the Capacities. As students learn the skills to voice their own literate currency in a caring environment, they begin to make meaning of their own developmental journey and embody this understanding in their life narrative.

Alvermann, D. E., Jonas, S., Steele, A., & Washington, E. (2006). Introduction. In D.E. Alvermann, K. A. Hinchman, D. W. Moore, S. E. Phelps, & D. R. Waff (Eds.), Reconceptualizing the literacies in adolescents’ lives (pp. xxi-xxxii). Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Baines, L. (2000). Performance art poetry. In L. Baines & A. J. Kunkel (Eds.), Going Bohemian: Activities that engage adolescents in the art of writing well (pp. 33-35). Delaware: International Reading Association.

Baines, L. & Kunkel, A. J. (Eds.). (2000). Going Bohemian: Activities that engage adolescents in the art of writing well. Delaware: International Reading Association.

Baines, L. & Kunkel, A. J. (2003). Teaching adolescents to write: The unsubtle art of naked teaching. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Duncan, A. (2009, October 22). Policy address on teacher education. Address at Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Gangi, J. (2004). Encountering children’s literature: An arts approach. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. London, UK: Routledge.

Goldstein, L.S., & Lake, V. E. (2003). The impact of field experience on pre-service teachers’ understanding of caring. Teacher Education Quarterly, 14, 1-13.

Greene, M. (2001). Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute lectures on aesthetic education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Levine, D. (2009). Building classroom communities: Strategies for developing a culture of caring. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Lincoln Center Institute. (2007, 2009). Aesthetic education, inquiry, and the imagination. New York, NY: Lincoln Center Institute.

McNamee, A., Mercurio, M. & Peloso, J. (2007). Who cares about caring in early childhood teacher education programs? Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 28(3), 277-288.

Neilsen, L. (1989). Living and literacy: The literate lives of three adults. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Neilsen, L. (1998). Knowing her place: Research literacies and feminist occasions. San Francisco, CA: Caddo Gap Press.

Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Obidah, J. E., & Marsh, T. E. (2006). Utilizing student’s cultural capital in the teaching and learning process: “As if” learning communities and African American students’ literate currency. In D.E. Alvermann, K. A. Hinchman, D. W. Moore, S. E. Phelps, & D. R. Waff (Eds.), Reconceptualizing the literacies in adolescents’ lives (pp. 107-127). Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Ringgold, F. (1988). Tar Beach [Painting]. Guggenheim Collection, New York. Retrieved from http://www.guggenheimcollection.org/site/artist_work_md_137_1.html

Ringgold, F. (1991). Tar beach. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Washor, E., Mojkowski, C., & Foster, D. (2009). Living literacy: A cycle of life to text and text to life. Phi Delta Kappan, 90(70), 521-523.

Zakin, A., & McNamee, A. (2009a). Wordless picture books are worth noticing deeply: A reflection on course design and implementation. Excelsior: Leadership in Teaching and Learning, 3(2), 28-42.

Zakin, A., & McNamee, A. (2009b, October). A secret of great teachers: Assessing the unassessable. Paper presented at the New York State Association of Teacher Educators, Saratoga Springs, NY.