Emergent Understandings: Multilingual Fourth Grade Students Generating Close Reading and Multimodal Responses to Global and Informational Texts

In this paper, the authors present findings from a yearlong ethnographic research study that examines the development of critical literacy within two urban fourth grade classrooms in Tennessee. This study examines how young second language learners in English-dominant classrooms, learn to read critically, write, and construct multimodal perspectives through global (texts focused upon world issues) and informational texts.

Introduction

In accordance with Donalyn Miller (2014), we wholeheartedly agree that "teaching students to read well and helping them to discover a love for reading aren't disparate goals (p. ix). The purpose of this paper is to explore how close reading and classrooms developing critical stances toward global and informational stories can co-exist. This research examines the role students and teachers play in focusing upon close reading as “critical analysis of texts” (Beers & Probst, 2012; Lehman & Roberts, 2013). Multimodal responses given by students and developed by two fourth grade teachers demonstrate the range of possible approaches to informational and global stories in the process of unraveling how a critical perspective plays a role in close reading. Additionally, we illustrate how a fourth grade community of learners with diverse knowledge of multiple languages “tries on” these texts and makes them their own as readers with knowledge and power.

The main research question for this research project is: How do young bilingual/urban children and their families respond critically to informational and global texts? A sub-question asks how teachers could design engagements to help these English language learning and urban students make meaning of and respond to the texts through close reading and a critical perspective.

Conceptual Orientation

In this paper, we draw upon sociocultural theories of learning and literacy (Vygotsky, 1978) as well as theories of discourse analysis and narrative analysis (Bloome, Carter, Christian, Otto, & Shuart-Faris, 2005). While the study examined various responses to texts, the research team paid attention to texts and contexts that were culturally authentic and relevant to the contemporary and diverse audiences of learners in today’s times (Street, 2005). Throughout this piece, when we use the word text we are referring to the broadest definition of the term in order to include film, art, music, as well as traditional forms of text, affirming our belief in an expanded definition of literacy (Gee, 2004; Lankshear & Knobel, 2011).

Emergent literacy research has demonstrated that reading books aloud and telling oral stories to children makes a difference in their language, vocabulary learning, and conceptual development for both first and second language learners, especially when adults hold conversations with children around reading (e.g., Bus, van Ijzendoorn, & Pellegrini, 1995; Collins, 2005; Fletcher, Cross, Tanney, Schneider, & Finch, 2008; Mol, Bus, deJong, & Smeets, 2008; Senechal, Pagan, & Lever, 2008).

Critical literacy research informs our understanding of building intentional space for critical connections with texts (Vasquez, Tate, & Harste, 2013). Close reading is an intense reading of a text that draws upon experience, thought, memory, and interpretation of the reader (Beers & Probst, 2012). Curricular decisions we made in concert with the classroom teachers involved in this study were grounded in social and cultural perspectives on literacy (Bloome & Egan-Robertson, 1993; Gee, 1999; Street, 2005) that highlight the cultural basis for reading and writing.

Given the diverse language and cultural backgrounds of the children with whom we work, we adopted a funds of knowledge approach aimed at tapping into existing literacy practices of children and their families as resources for bridging the gap between home and school (Compton-Lily, Rogers, & Lewis, 2012; Moll, Saez, & Dworin, 2001). Teachers adopting a funds of knowledge perspective intentionally design ways to learn about students, their families, and their communities.

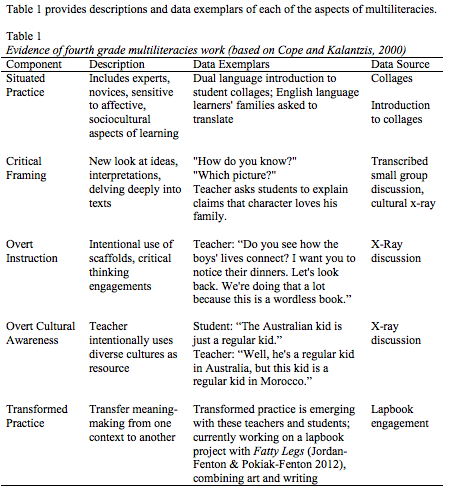

The intentional designing of curricula echoes the four major aspects of multiliteracies theory developed by Cope and Kalantzis (2000): situated practice, critical framing, overt instruction, and transformed practice. Situated practice refers to collaboration among experts and novices, with sensitivity to sociocultural aspects of learning. Critical framing requires a new look at existing thought, possibly reconsidering long-held notions, or creating new ideas. Overt instruction entails deliberate scaffolding of instruction and intentional use of critical thinking engagements. Finally, transformed practice transfers meaning making from one learning experience to another. These concepts will be examined in more depth in the Findings section.

Researcher Positioning

It is our stance that all learners need authentic literacy experiences that facilitate learning and create opportunities to collaboratively examine analytical texts that invite them to see critical connections. In the United States’ current political context, many parents and students experience a severe loss of power in the curricular decisions that ultimately affect student learning. Children’s responses to literature show connections between literature, linguistic diversity and identity issues particularly those related to how children read and respond critically to the word and the world (Freire, 1970).

As researchers we served multi-faceted, dynamic roles as both teachers and researchers. We offered professional development to participating teachers and also taught model lessons in their classrooms once a week, and our dual roles as teachers and researchers helped inform our research and simultaneously improved instruction for both classroom teachers and their students. We acknowledge the tensions produced by the multiple identities we assumed in the context of this project. We believe, however, that the teachers also took on additional roles as observers and analyzers of both the authors' lessons and their own, thus transforming their practices, as will be addressed in later sections of this paper.

Methodology

Participants and Research Context

This yearlong ethnographic study took place at Canyon Ridge Elementary (pseudonym) located in Tennessee. The school was selected as a research site due to its diverse student population. After receiving permission and approval from the school's principal, the second author invited teachers to join the project by presenting an overview of the project at the end of the past school year. Nine teachers from kindergarten through fourth grade volunteered and joined the study. This paper focuses on two fourth grade classrooms, with approximately 23 students in each class. Students in these classrooms speak Arabic, Spanish, French, Italian, and English.

The research team held professional development sessions for teachers each month, beginning with an overview of the project outlined in a meeting prior to the start of school. Teachers received book bins filled with global and informational texts carefully selected by the researchers. Each grade level's bin contained the same set of texts, although a few texts were selected for all teachers, such as Jacqueline Woodson's Each Kindness (2012). The researchers studied various sources of information and reviews for book selection, including the Worlds of Words organization; the International Board on Books for Young People; the United States Board on Books for Young People; Orbis Pictus; Caldecott, Newbery, and Hans Christian Andersen Award winners; Pura Belpre; Coretta Scott King; Americas; Bookbird; Horn Book; the American Library Association; Language Arts; and Amazon.com. Representation of a variety of ethnicities, genders, cultures, identities, and languages were significant aspects considered during selection.

Classroom teachers employed global and informational texts in their classrooms in strategic and intentional ways. Interviews conducted at the beginning of the study revealed that teachers lacked clarity about both close reading and critical literacy, and therefore the researchers worked collaboratively with the teachers in professional development and grade-level planning sessions to develop understanding. The monthly professional development sessions offered examples and discussion of various strategies, such as text rendering, read-alouds, and cultural x-rays (Short, 2009). Additionally, the research team provided some conceptual frames, such as a critical literacy overview, in order to help teachers understand how to teach reading from a critical stance (McLaughlin & DeVoogd, 2004; Van Sluys, Lewison, & Flint, 2006).

Procedures: The Texts and Responses

We selected one central text and response engagement as the focus of our analysis, though we occasionally refer to others to support our findings. The two fourth grade classes read Jeannie Baker's wordless, multi-media picture book, Mirror (2010). Following introductions written in both English and Arabic, the book juxtaposes a day in the life of an Australian boy with a day in the life of a Moroccan boy. Mrs. Barnett and Mrs. Johnson, two participating teachers, designed several text engagements to help their students make meaning of the text: a cultural x-ray (Short, 2009) of each boy, created in small groups; a cloth collage response illustrating four parts of a day in the life of the student; and a dual language introduction to the collage made by pairs of English-speaking students and English learners. The families of the English learners were invited to translate the introduction into their home language.

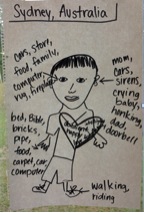

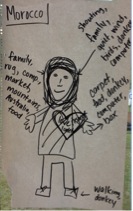

After reading the text in a whole-group setting, Mrs. Barnett worked with a small group of students during a center rotation on cultural x-rays (Short, 2009) of the two boys featured in Mirror (2010). The purpose of the cultural x-ray is to explore both external and internal features of a character in order to situate him in his particular culture. Students determine what kinds of outer characteristics to draw, such as clothing or hairstyle, as well as what should go in the “heart” section, signifying what matters most to the character. Figure 1 shows the two x-rays the fourth graders created.

Figure 1. Cultural X-rays of Boys in Mirror

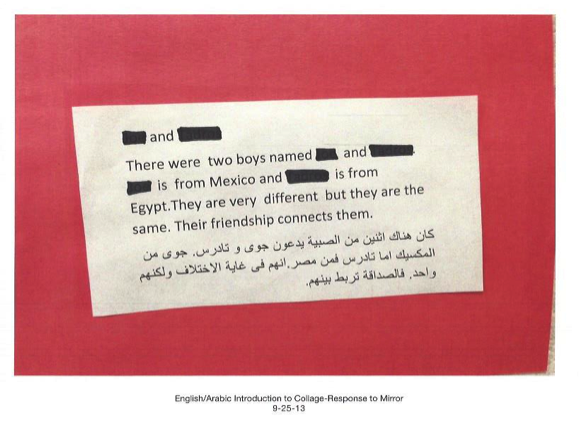

Following the cultural x-ray engagement, the teachers asked the students to create a multi-media collage representing a day in their own lives. The only parameters were that 1) the collage needed to show four parts of a day in sequence just as Baker (2012) showed in the wordless text and 2) the students must write an introduction to the day, just as the author did in Mirror (2010). One English-speaking child was paired with one English learner, so that the introduction could be a dual language piece of writing. The English learners' families were invited to help translate the introduction into the language they spoke in their homes. Figure 2 shows an example of a collage introduction created by students Juan and Hanif (pseudonyms).

Figure 2. Dual Introduction to the Collage.

Cloth, card stock, yarn, beads, and other materials were available for the students to use as they designed the four-sectioned collage representing various parts of a day in their lives. Figure 3 shows an example of a student's collage.

Figure 3. Student Collage Representing a Day.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative analysis of the learners’ literacy and sociolinguistic competence will be examined from a sociocultural perspective. Data collection included field notes taken during participant-observation sessions in both classrooms for a minimum of one day a week for one school year; photographs of children and families’ multimodal responses; as well as audio, digital, and video recordings of lessons taught by both the researchers and by classroom teachers.

Data analysis was ongoing and was initially analyzed using thematic and grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), content analysis (White & Marsh, 2006), and multimodal analysis (Jewitt et al., 2009). First, we read and reread the field notes and transcribed class discussions and video transcriptions a minimum of three times looking for key themes and patterns (Bogdan & Biklen, 2006). Next, we coded the field notes and transcriptions as the themes and patterns emerged and collapsed similar categories into single codes. For example, the codes requiring text evidence and asking to rethink a claim were both related teacher-to-student requests, and so these separate categories merged into a single category we called critical framing.

Finally, as we narrowed the categories by collapsing similar findings into a single category, we "read the data through the literature" (D. Rowe, personal communication, December 15, 2013). Reading our data through the multiliteracies literature (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000) provided a lens through which we analyzed the teachers' and students' actions as designers. Returning to the data for this third level of analysis explained how the multimodal responses to texts worked from both a close reading perspective and from a critical stance.

Findings

The data showed that all classroom stakeholders were acting as designers to make meaning of the texts. The students and teachers utilized three of the four aspects of multiliteracies, and we found emergent evidence of the fourth aspect.

Students as Designers of Meaning

Content analysis (White & Marsh, 2006) of a transcribed conversation between the teacher and students suggested that the students were employing intertextuality by connecting the text Mirror (2010) to other texts they knew. For example, in the cultural x-ray discussion, upon discovering that the Australian boy lived in Sydney, a student remarked, "That's the city in Finding Nemo (2003)!" Several other students also recognized the city from the movie and articulated this connection. Another student made a cross-curricular connection to social studies when the Moroccan boy was shown trading a sheep. "He's bartering!" the student declared, producing the word as the text showed only pictures of the event. The teacher supported his connection by reiterating, "Yes, it's the word we learned in social studies. He's using a lamb for money." By drawing on their prior knowledge of a place, Sydney, and a vocabulary word, barter, the students were able to understand Mirror (2010) in a deep way by integrating new meanings with previous information.

Teacher as Engagement Designer

Mrs. Barnett acted as a designer in this engagement by providing what Cope and Kalantzis (2000) refer to as critical framing, overt instruction, and a third category identified as overt cultural awareness. Critical framing occurs when the teacher designs an assignment, here a response to the text, in which students must look at ideas in a new way or create a new interpretation of an existing perspective. The transcription showed that critical framing occurred when some of the students thought that the two boys in the different countries were actually the same boy, and that they were both selling rugs. "Are they the same?" Mrs. Barnett asked. "Take another look. Is she [the student making claim] right? Or just on the right track?" By asking the students to look carefully at the pictures, the teacher was helping the students to think more critically about what was actually happening in the story. The students revised their initial idea after seeing that although the boys were doing many of the same kinds of daily activities, they were two different people. She did not simply correct the student's mistake, but instead helped her to determine, through a second look at the illustrations, that her original idea needed to be reconsidered. By guiding the students to employ a close reading tenet—revisiting the text—Mrs. Barnett set the lesson in a critical frame.

As the students decided how to represent the Moroccan boy's internal characteristics, one fourth-grader suggested that they write, "loves his family," in the heart section of the cultural x-ray. "Mrs. Barnett did not immediately write this in the heart, but instead asked, "How do you know he loves his family?" The student then looked back at the text and supported his claim by referring to a page where the boy was depicted spending time with his family.

One of the ways Mrs. Barnett designed this engagement to help students to think critically was by employing overt instruction (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000). This kind of instruction includes intentional scaffolding to help students be able to think critically and to use language and art as resources. Mrs. Barnett reminded her students to look back at the pages: "Let's look back. We're doing that a lot because this is a wordless book."

The transcribed discussion also revealed a category we have termed overt cultural awareness. This category refers to instruction that intentionally attends to cultural features in a sensitive way, focusing on cultural differences as a resource for students, rather than a detriment or means of isolation. The data illustrated teachers' overt cultural awareness on multiple levels. One example, from our video data, came from a butter-making response to the book, The Butter Man (Alalou & Alalou, 2011). As the students shook their cream to form butter, Mrs. Johnson asked them each to share a special food his or her family enjoyed. Students enthusiastically raised hands to tell about "pork salad," "pigs in a potato patch," and "pigs in a blanket." One student described how his family ate the meal "all together," and another explained the order of ingredients used in a recipe. Mrs. Johnson efficiently used a moment where students were busily shaking their butter containers to connect their own lives to the story they had read about an African boy who loves butter.

The cultural x-ray discussion presents another helpful example of overt cultural awareness. Mrs. Barnett was purposeful in the language she and the students used to discuss the Moroccan and Australian characters. When the students were determining some of the outer characteristics to include in the cultural x-ray, one of the fourth-graders suggested that the Moroccan boy needed a "hoodie." "Head wrap," Mrs. Barnett corrected gently. Following this comment, another student remarked, "The Australian kid is just a regular boy." In the book, the Australian boy's clothing looks similar to the clothing the participants wear, but the Moroccan boy's clothing is quite different. In response to the student's evaluation of the Australian boy as "regular," Mrs. Barnett replied, "Well, he's a regular kid in Australia, but this kid is a regular kid in Morocco." Specificity of language, especially when it reflects cultural awareness was important to the teacher, and she wanted her students to recognize the differences in head wrap and hoodie and to consider the meaning of their use of the word regular.

In the collage introduction, shown in Figure 2, the authors, Juan and Hanif, recognize their own differences, stating, "We are very different." Yet they celebrate the connection between them: their friendship. By displaying the collages and introductions in the hallway for all of the Canyon Ridge community to view, Mrs. Johnson and Mrs. Barnett were overtly showing how much they valued the diverse cultures of their students and the students' families.

Situated Practice

Mrs. Johnson, who designed the collage engagements, created a situated practice (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000) in which experts and novices worked in concert on an assignment that was intentionally sensitive to sociocultural and affective aspects of learning. By inviting the families of her students to translate the introduction to the collages into their home language, the teachers were showing the students that they honored the diversity of languages in their classrooms as well as their families' expertise. Overt practice can be seen in this exercise also, as the introductions to Mirror (2010) were used as mentor texts, or models for the students' work.

The student collage shown in Figure 3 is an example of hybridization (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000), in which students make meaning from a text in a nontraditional way. No language is used in the collage: the student used art as a resource to show sleeping and then waking with arms outstretched; a staircase to show coming downstairs for breakfast; illustrated the school day with a dress, book, and something to say about the book; and finally, she depicted night with an image of being in bed again. Art is used as a resource to convey meaning without language in the same way the wordless picture book expressed a day in the life of its two characters.

Transformed Practice

Transformed practice (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000) consists of transferring what has been learned from one context to another, applying and amending new ideas or interpretations that have been learned through the previous aspects of the multiliteracies work; situated practice, overt instruction, cultural framing, and for the current study, overt cultural awareness. The two fourth grade teachers are showing evidence of their transformed practice as the school year progresses, in particular by providing more opportunities for students to make meaning of texts through art or drama. Mrs. Johnson's students engaged in a tableau text response through acting out various scenes from Jane Yolen's Encounter (1992), a counter-narrative to the normative idea of the discovery of America. In the other classroom, Mrs. Barnett's students drew portraits of the main character in Fatty Legs (Jordan-Fenton & Pokiak-Fenton, 2010) as a springboard for a written response.

Conclusions, Implications, Future Directions

While the grant team has introduced these fourth grade teachers to the global and informational texts through professional development, the teachers themselves have creatively and intentionally designed engagements for their students to "broaden diversity of signs and cultural meanings that circulate in the classroom" (Jewitt, 2008, p. 262).

The research questions focused on how bilingual and urban students and their families would construct meaning and responses to global and informational texts through a close reading and critical perspective and how the teachers might guide this process. The findings showed that the students acted as designers (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000), connecting new information to prior knowledge through intertextuality. Families were instrumental in translating the introductions to the collages in their home languages, and as these pieces were hung in the hallway, the collaboration between the English speakers and the English language learners and their families was honored and celebrated through this funds of knowledge approach (Compton-Lily, Rogers, & Lewis, 2012; Moll, Saez, & Dworin, 2001).

Teachers guided the close reading and critical perspectives of their students by providing scaffolding, mentor texts, aspects of situated practice and an overall sociocultural approach (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000; Vygotsky, 1978). The engagements the teachers offered required returning to the texts repeatedly, an essential component of close reading as the students connected their own experiences, thoughts, memories, and interpretations to the text (Beers & Probst, 2012). By using both critical framing and overt cultural awareness, the classroom teachers not only led the students to read and reread closely and carefully, but they also asked the students questions that demanded critical thought and often required revision of an initial idea or belief about the text.

The findings from this study suggest several classroom implications. First, critical reading and close reading are not mutually exclusive; these two kinds of reading can, as Miller (2014) asserted, coexist. For both critical and close reading to occur, the teacher needs to act as a designer, carefully structuring particular opportunities with high quality, high interest texts. By adopting a funds of knowledge approach, teachers can draw on the skills and talents of students' families, creating a community of situated practice where experts and novices are working in concert (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000). For bilingual learners, having their home languages celebrated as a resource could be highly motivating, and the use of art as a resource can help English language learners make meaning from the texts without a language obstacle. Critical framing and overt cultural awareness can help students to revise initial thoughts or to create fresh ideas with new information. With the multitude of demands being placed on teachers today, it seems optimal to combine close and critical reading instruction as a way to increase engagement and meaning making with texts.

Directions for future research might include evaluating students' written responses to the texts following the close and critical reading strategies instruction. Evaluating the progress of bilingual students' writing and the relationship between the artistic engagements and their writing growth could be highly beneficial information for classroom teachers. Using technology as a tool for both art and writing might be another way for teachers to help bilingual and English speaking students, and an analysis of technology's role in the combination of critical and close reading might be useful.

Alalou, E., & Alalou, A. (2011). The butter man. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge Publishing.

Baker, J. (2010). Mirror. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Beers, K., & Probst, R. (2012). Notice and note-taking: Strategies for close reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Bloome, D., & Egan-Robertson, A. (1993). The social construction of intertextuality in classroom reading and writing lessons. Reading Research Quarterly, 28(4), 304-333.

Bloome, D., Carter, S. P., Christian, B. M., Otto, S., Shuart-Faris, N. (2005). Discourse analysis and the study of classroom language and literacy events: A microethnographic perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2006). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Bus, A. G., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1995). Mothers reading to their three-year-olds: The role of mother-child attachment security in becoming literate. Reading Research Quarterly, 30, 998-1015.

Collins, M. F. (2005). ESL preschoolers' English vocabulary acquisition from storybook reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(4), 406-408.

Compton-Lilly, C. (2009). Listening to families over time: Seven lessons learned about literacy in families. Language Arts, 86(6), 449-457.

Compton-Lily, C., Rogers, R., & Lewis, T. (2012). Analyzing epistemological considerations related to diversity: An integrative critical literature review of family literacy scholarship. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(1), 33-60.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2000). Multiliteracies: Lit learning. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Fletcher, K. L., Cross, J. R., Tanney, A. L., Schneider, M., & Finch, W. H. (2008). Predicting language development in children at risk: The effects of quality and frequency of caregiver reading. Early Education and Development, 19(1), 89-111.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing.

Gee, J. P. (1999). An introduction to discourse analysis. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2002). A sociocultural perspective on early literacy development. In D. Dickinson & S. Newman (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 30-42). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Gee, J. P. (2004). New times and new literacies: Themes for a changing world. In A. F. Ball & S. W. Freedman (Eds.), Bakhtinian perspectives on language, literacy and learning (pp. 279-306). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chancery Lane, London: Aldine Publishing Co.

Jewitt, C., Kress, G., & Mavers, D. (Eds.). (2009). The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. London, UK: Routledge.

Jordan-Fenton, C., & Pokiak-Fenton, M. (2010). Fatty legs: A true story. Toronto, Canada: Annick Press.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2011). New literacies: Everyday practices and social learning. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill International.

Lehman, C., & Roberts, K. (2014). Falling in love with close reading: Lessons for analyzing texts–and life. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

McLaughlin, M., & DeVoogd, G. L. (2004). Critical literacy: Enhancing students' comprehension of text. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Miller, D. (2014). Foreword. In C. Lehman & K. Roberts, Falling in love with close reading: Lessons for analyzing texts–and life (pp. viii - xi). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Mol, S. E., Bus, A. G., deJong, M. T., & Smeets, D. J. H. (2008). Added value of dialogic parent-child book readings: A meta-analysis. Early Education and Development, 19(1), 7-26.

Moll, L. C., Saez, R., & Dworin, J. (2001). Exploring biliteracy: Two student case examples of writing as social practice. The Elementary School Journal, 101(4), 435-449.

Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. New York, NY: Routledge.

Senechal, M., Pagan, S., & Lever, R. (2008). Relations among the frequency of shared reading and 4-year-old children's vocabulary, morphological and syntax comprehension and narrative skills. Early Education and Development, 19(1), 27-44.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 47(2), 1-10.

Stanton, A., & Unkrich, L. (Directors). (2003). Finding Nemo [motion picture]. United States: Disney/Pixar.

Street, B. (2005). Literacy, technology, and multimodality: Implications for pedagogy and curriculum. Paper presented at the 55th Annual Meeting of the National Reading Conference. Miami, FL.

Van Sluys, K., Lewison, M., & Flint, A. S. (2006). Researching critical literacy: A critical study of analysis of classroom discourse. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(2), 197-233.

Vasquez, V., Tate, S., & Harste, J. C. (2013). Negotiating critical literacies with pre-service and in-service teachers. New York, NY: Routledge Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Woodson, J. (2012). Each Kindness. New York, NY: Penguin.

White, M. D., & Marsh, E. E. (2006). Content analysis: a flexible methodology. Library Trends 55(1), 22-45.

Wiley, T. G., & de Klerk, G. (2010). Common myths about literacy and language diversity in the multilingual United States. In S. N. Lukanovič (Ed.), A shared vision—A global paradigm to promote linguistic and cultural diversity (pp. 107-143). Ljubljana, Slovenia: Slovene National Commission for UNESCO.

Yolen, J. (1992). Encounter. Boston, MA: Harcourt.