A conceptual proposition to if and how immigrants' volunteering influences their integration into host societies

This study explores whether and in what ways immigrant volunteering may serve as a conduit for immigrant integration into the host society. Using a conceptual approach, I examine several social theories explaining the process's dynamics. I find that while existing social theories may explain ways volunteer activities positively influence the relationship between immigrants and nonimmigrants, they do not account for additional barriers newcomers experience during resettlement. Using insights from sociology, an intersectional approach expands knowledge in the area of immigrant-nonimmigrant relations by exploring volunteering as a means to support and improve immigrant integration.

Keywords: immigrant volunteering; immigrant integration; conceptual research; intersectionality

Acknowledgments

I thank Roberta Iversen for her mentorship and guidance while writing this paper. I appreciate comments by peers at the ARNOVA Doctoral Workshop session—especially Itay Greenspan and Rebecca Nesbit. I also thank the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for valuable comments on the paper's prior version.

As global immigration remains at an all-time high (Esses and Abelson, 2017; National Academies Press, 2015), immigrant integration has become an urgent and contended topic across the world. Literature defines integration as the extent to which immigrants have the capacity and knowledge to live a successful and fulfilling life in the host society (Harder et al., 2018)—with capacity consisting of immigrants' social capital, relationships, and networks; and knowledge reflecting a fluency of language and ability to navigate political and social institutions in the host country (Harder et al., 2018). The quantity and quality of newcomer interactions and social ties with nonimmigrants comprise measures of social integration (Harder et al., 2018; Wang and Handy, 2014). One activity that encourages social integration is voluntary work, as volunteer settings provide a space for goal-oriented relationship-building (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

Research on immigrant volunteering is nascent (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Sinha, Greenspan, and Handy, 2011; Wang and Handy, 2014). While some studies have explored the benefits of voluntary work, few papers analyze the benefits of volunteering for immigrants (Baert and Vujic, 2016; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). Literature reveals that the benefits and drawbacks of immigrant volunteering depend strongly on social exchanges between newcomers and nonimmigrants (Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). Essentially, beneficial effects require certain inter-ethnic conditions. For example, a mutually beneficial setting guarantees that both immigrants and nonimmigrants have a similar or equal status, shared goals and are able to maintain regular interactions over time (Pettigrew, 1998; Oliver, 2010). Literature also suggests that ethnic strife can be prevented when people of different ethnic backgrounds participate in multiethnic volunteer associations (Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019; Yap et al., 2011). However, existing studies rarely apply explicit social theories when analyzing interactions between immigrant volunteers and their native-born counterparts.

This study adds to the literature by applying a conceptual approach that integrates existing constructs and theories (Corley and Gioia, 2011; Gilson and Goldberg, 2015; Marek, 2015) to explore whether and in what ways immigrant volunteering enhances social integration into the host country. In addition, I ask how immigrant volunteering influences integration into the host society. The paper proceeds as follows: First, I review existing studies on volunteering and integration and outline the theoretical concepts underlying my exploration; then, I present a method to explore the process of moving from immigrant volunteering to immigrant integration. Lastly, I discuss my findings and the limitations of the research and offer recommendations for future studies.

Background and Significance

Immigrant Integration. Harder et al. (2018) define integration as an immigrant’s capacity and knowledge to build a fulfilling and successful life while maintaining their own culture. The definition emphasizes the immigrant’s ability to achieve their vision and life goals and realize their potential in the host society (Anthias, 2012; Harder et al., 2018) - while being careful not to equate integration with assimilation, as the latter requires immigrants to discard their home country’s culture (Anthias, 2012; Danso and Lum, 2013; Esses and Abelson, 2017). Scholars argue that immigrants can increase their capacity and knowledge by becoming civic participants and engaging in voluntary work (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Sinha et al., 2011; Wang and Handy, 2014), implying that volunteering can improve newcomer integration into the host society (Baert and Vujić, 2016; Manatschal and Stadelmann-steffen, 2014; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

Immigrant Volunteering. Research defines immigrant volunteering as volunteer work conducted by foreign-born individuals for causes or individuals without expectations of rewards (Sinha et al., 2011; Wilson, 2000; 2019; Qvist, 2018). The last few years have presented a noteworthy increase in research on the social benefits newcomers acquire through volunteering (Handy and Wang, 2014; Manatschal and Stadelmann-steffen, 2014; Weisinger and Slipante, 2005). For instance, recent studies explore immigrant volunteering as a tool for self-improvement and a means to build networks and obtain job-related skills (Baert and Vujić, 2016; Raza et al., 2013; Sali, 2021; Yap et al., 2011). Research also shows that volunteering cultivates mutual trust between immigrants and nonimmigrants through exchanges of mutually valued services (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Sinha et al., 2011; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). This paper investigates the association between immigrant volunteering and integration through the following theoretical and conceptual frameworks.

Theory

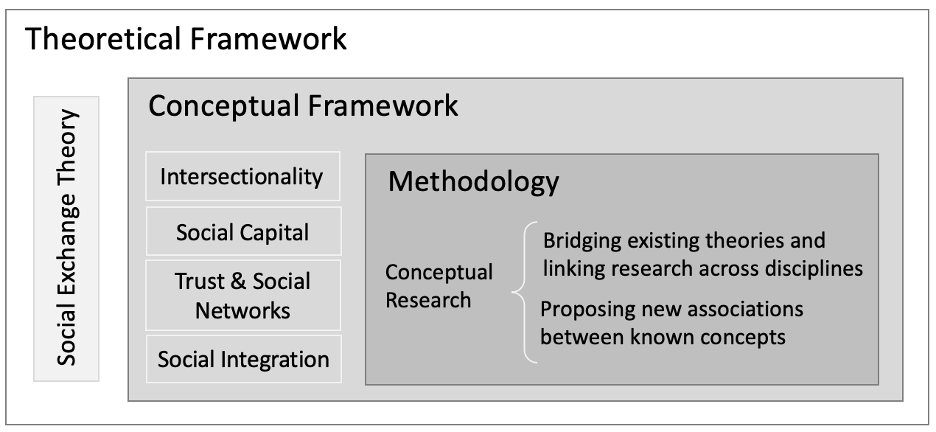

Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework consists of a single theory that is the primary means by which the research question is understood and investigated (Ravitch and Carl, 2019; Ravitch and Riggan, 2016). The present study’s theoretical framework is social exchange theory, which argues that relationships and mutual exchanges between individuals and groups are created through a cost-benefit analysis (Cook, 2015; Stryker, 2001). The theory explains that individuals will opt for an action if they believe they will extract a reward greater than the cost of performing the action. (Cook, 2015; Jonason and Middleton, 2015; Stryker, 2001). For example, current research on immigrant volunteering shows that immigrants choose to volunteer expecting intangible rewards, such as improved language skills or networking opportunities, social capital, and personal empowerment in exchange for their time and effort (Khvorostianov and Remennick, 2017; Wilson, 2000). On the other hand, nonimmigrants will accrue “costs” such as training resources catered explicitly to immigrants who are invited and wish to join the volunteer force (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). However, the main benefit for nonimmigrants would be accessing a previously untapped volunteer power (Couton and Gaudet, 2008; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). If we understand volunteering as a service that helps immigrants and nonimmigrants increase benefits over costs on both ends, we can presume that their interpersonal attraction will grow (Lott and Lott, 2019; Oliver, 2010).

Conceptual Framework

A conceptual framework comprises several formal theories that capture the studied phenomena holistically. This framework shows existing relationships between ideas and how they relate to the research question (Corley and Gioia, 2011; Ravitch and Carl, 2019; Ravitch and Riggan, 2016). The conceptual framework of this study includes: 1) Crenshaw’s intersectionality, 2) Bourdieu’s social capital, 3) Coleman’s trust and social networks, and 4) Blau’s social integration.

Crenshaw’s Intersectionality. Intersectionality originally described how policies and traditional feminist notions excluded Black women due to multiple forms of discrimination (e.g., based on gender and race) they experience (Choo and Ferre, 2010; Crenshaw, 1990; Daftary, 2020). Crenshaw (1990) examines how social categorizations (e.g., class, ethnicity, gender, etc.) act as interdependent categories of disadvantage (Duran and Jones, 2020). For instance, a Christian, U.S.-born, Black woman will experience different disadvantages than a Muslim, non-U.S.-born, Black woman. Existing literature describes intersectionality as an analytic tool to capture the complexity of group experiences more than a theory, per se (Cho et al., 2013; Daftary, 2020; Stasiulis et al., 2020). Applying intersectionality to the case of immigrants allows for a detailed view of how particularly marginalized groups experience the cumulative effects of various forms of discrimination. Intersectionality may also enhance the understanding of how immigrants volunteer to find shared interests with nonimmigrants (Anthias, 2014; Wilson-Forsberg and Sethi, 2015). Based on intersectionality’s central principles, we should examine immigrant experiences through the intersecting social categories shown in their lives (Daftary, 2020; Davis, 2008; Hankivsky and Cornier, 2009). Immigrants are likely to endure identity-based inequalities related to immigration status, age, gender, class, ethnicity, and religion, among others (Crenshaw, 1990; Duran and Jones, 2020; Wilson-Forsberg and Sethi, 2015). Yet, studies on immigrants rarely account for the comprehensive range of identity issues newcomers experience as they resettle and strive to integrate (Kaushik and Walsh, 2018; Stasiulis et al., 2020). Therefore, intersectionality is an attractive proposition, as it invites debate addressing injustices that emerge from multiple categories of difference (Anthias, 2010; Daftary, 2020; Duran and Jones, 2020). While intersectionality may help explain the difficulties immigrants encounter when resettling, the concept of social capital may assist in mitigating these difficulties, as described by Bourdieu (2001).

Bourdieu’s Social Capital. Bourdieu’s (2001) objective was to reveal the dynamics and tensions of societal power relations. He defines social capital as a set of obligations between parties, such as social exchanges, reciprocity, shared norms, and trust (Bourdieu, 2001). Social capital is particularly instructive when analyzing how volunteering impacts structural constraints and unequal access to organizational resources based on ethnicity, gender, and class. We may apply Bourdieu’s theory to the discussion of immigrant volunteering as means to understand how newcomers access actual and potential capital through volunteering (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

Research reveals that civically active immigrants access social capital through genuine relationships with people in their networks (Nakhaie and Kazemipur, 2012; Raza et al., 2012; Wang & Handy, 2014). Such relationships require personal investment, reciprocity, and continuous maintenance (Bourdieu, 2001; Oliver, 2010; Sali, 2021). Bourdieu (2001) argues that increased social capital is more significant for those in lower echelons of the social hierarchy, threatened by economic or social decline—a distinguishing feature of most immigrants. Conversely, voluntary settings offer environments where mutual recognition is prevalent (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Raza, Beaujot, and Woldemicael, 2012). Participation in a joint interest group allows for a trust-based transfer of social capital between immigrants and nonimmigrants.

Coleman’s Trust and Social Networks. In line with Bourdieu, Coleman (1988) states that social capital constitutes all the resources individuals can use to realize their interests in society (e.g., trust, networks, etc.). Coleman (1988) also argues that social structures, such as networks and norms, facilitate trust as a form of social credit. This argument stresses that most trust relations are not unilateral and that reciprocal trust relations are mutually reinforcing (Coleman, 1988; Handy and Mook, 2011; Luiz Coradini, 2010). Coleman would describe social capital in terms of social networks and their phenomena, such as dependency, consultation, obligations, and access to information (Coleman, 1988; Luiz Coradini, 2010; Dahinden, 2013). Such aspects of social capital are all benefits that may be acquired through volunteering (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Sinha et al., 2011; Wang and Handy, 2014). However, Coleman would also argue that since social capital is less liquid than other forms of capital, social structures that generate social capital are only helpful for specific objectives (Coleman, 1988; Dahinden, 2013; Sobel, 2002). In other words, volunteering in certain organizations may generate social capital for particular goals (Sobel, 2002; Nesbit, 2017). For instance, Nesbit (2017) finds that an immigrant volunteering in a political nonprofit gains knowledge, experience, and contacts from political networks. However, while this type of volunteering may facilitate the immigrant’s political integration (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Nesbit, 2017), it does not necessarily lead to increased feelings of, say, social integration. Conversely, volunteering for people in need and community-centered initiatives have been shown to improve perceptions of social integration (Ruiz, Wang, and Handy, 2021; Khvorostianov and Remennick, 2017).

Blau’s Social Integration. Harder et al.’s (2018) definition of immigrant integration complements Blau’s definition (2008): social integration as the bonds of attraction that unite group members into a single unit. Literature also describes social integration as the process of agreeing on a shared system of meaning, language, and culture (Björkman et al., 2007; Blau, 2008). This definition implies that increased social incorporation reduces cultural conflict and increases perceptions of integration (Dahinden, 2013; Björkman et al., 2007; Oliver, 2010). Essentially, intergroup tensions diminish when minority group members engage in activities that make them more “attractive” to the dominant group (Blau, 2008; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). This attractiveness can be enhanced by sharing and providing services valued by the host society—such as volunteering (Blau, 2008; Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Yap et al., 2010). For example, suppose specific individuals share their resources and talents with others (e.g., when immigrants volunteer where their language and cultural knowledge is needed). In that case, the dominant group may lower their defenses and feel attracted to immigrant volunteers, perhaps even resulting in social integration.

Methods

The methodology used for this paper is conceptual research, undertaken by collecting and analyzing information on immigrant volunteering (Corley and Gioia, 2011; Marek, 2015; Weick, 1989). A conceptual paper differs from a theoretical paper in that instead of reporting on a specific theory; it maps the conceptual terrain of a phenomenon (e.g., immigrant volunteering) by identifying and integrating disparate concepts (e.g., intersectionality and social exchange theory) into a new framework from which to generate new ideas and theories (McGregor, 2018).

As with other conceptual papers, the present research does not suggest a new theory at a construct level. Instead, it bridges existing theories, linking research across disciplines to broaden the scope of thinking (Corley and Gioia, 2011; Gilson and Goldberg, 2015). In other words, this conceptual study integrates and proposes new associations among known constructs to develop a logical and complete argument for the relationship between immigrant integration and volunteer activities (Marek, 2015; Weick, 1989). I present propositions that link to testable hypotheses, offering a bridge between usefulness and validation of existing realities (Gilson and Goldberg, 2015; Weick, 1989) while aiming to explain if and how civic participation impacts immigrant integration as defined by Harder et al. (2018).

First, a literature review lists external and internal influences; second, a reflective analysis adds influences not found in mainstream literature. I then analyze impacts and group them into factors I integrate into a conceptual model, showing external and internal factors. I follow up with a revised model, visualized in an instructional figure. Lastly, I develop recommendations for future research. Overall, I limit the analysis to a discussion of social theories closely related to volunteering and integration. While the list of theories is not exhaustive, this paper’s objective is to emphasize critical aspects of how these two areas are connected and how minority-sensitive approaches benefit immigrants and the host society.

Figure 1

Frameworks and Methodology

Discussion

When applying the theories by Bourdieu, Coleman, and Blau, I aim to uncover how immigrant volunteering may lead to general immigrant integration. An immigrant’s story begins when a foreign-born individual emigrates to a host country. There are several reasons a person may decide or have to relocate. Significant reasons for immigration are to (a) find better job opportunities, (b) secure better living conditions, (c) access better education, (d) join American family members, and (e) escape a troubled country (Esses and Abelson, 2017; Kunz, 2003; National Academies Press, 2015). However, while seeking these benefits, immigrants often struggle to acclimate (National Academies Press, 2015; Wang and Handy, 2014), with power relations in the host society as a significant barrier (Daftary, 2020; Oliver, 2010).

Many nonimmigrants enjoy easy access to resources through a durable network of institutionalized relationships. By contrast, newcomers often lack connections and visibility in the host society (Erel, 2010; Kunz, 2003; Yap et al., 2010). Yet, this type of social capital is necessary for immigrants to integrate (Kunz, 2003; Raza et al., 2012; Nakhaie and Kazemipur, 2012). However, the creation of social capital also tends to reproduce status, and power relations (Bourdieu, 2001; Erel, 2010; Sobel, 2002), which is why Bourdieu emphasizes that access to social capital depends on structural constraints related to class, gender, and ethnicity (Bourdieu, 2001; Luiz Coradini, 2010). This suggests that the creation of social capital is highly reliant on the context of specific social spaces (Coleman, 1988; Luiz Coradini, 2010), prompting the question: Where can immigrants accrue resources and capital, despite preexisting societal power relations? Volunteering venues offer social settings with few entry barriers where immigrants can gain material and immaterial capital (e.g., reference letters, networking, and job referrals) (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

Furthermore, generating social capital is most effective in environments of mutual recognition (Bourdieu, 2001; Luiz Coradini, 2010; Oliver, 2010)—which is typical in voluntary settings. Research shows that volunteering towards a common goal acts as an equalizer between volunteers, reducing power inequalities (Erel, 2010; Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). Immigrants with active volunteer networks have easier access to social capital through relationships with nonimmigrant volunteers (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; National Academies Press, 2015; Weisinger and Slipante, 2005). Literature also indicates that immigrants’ most valuable sources of social capital are their contacts with established nonimmigrants (Oliver, 2010; National Academies Press, 2015; Weisinger and Slipante, 2005). Therefore, capital derived from volunteering may be of greater value to those not economically or socially established.

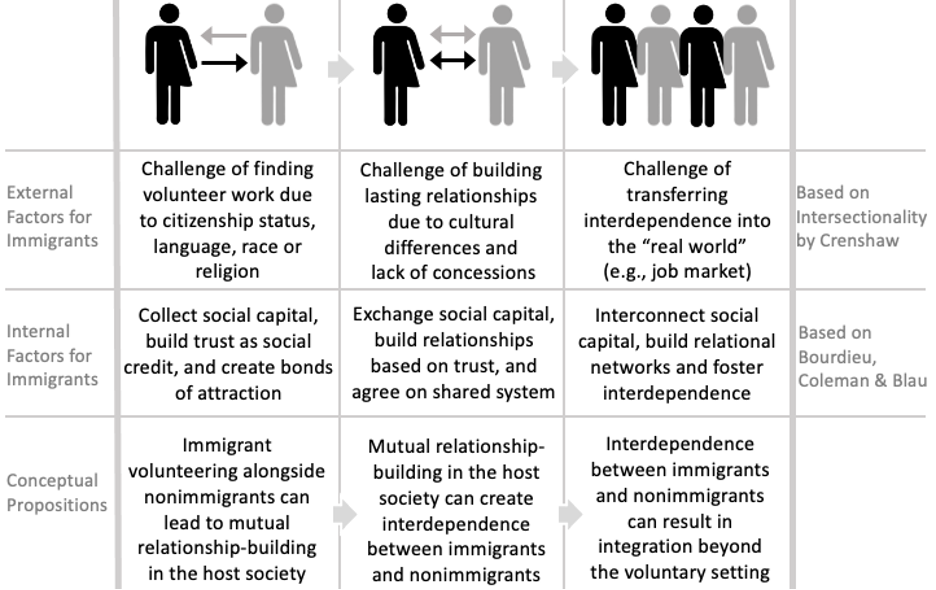

I expand this suggestion with Crenshaw’s (1990) theory on intersectionality. Networks provide different values to different people for various purposes, depending on their location in the host society’s hierarchy (Anthias, 2012; Luiz Coradini, 2010). The social value of identity categories (e.g., “immigrant,” “widow,” etc.) and their interrelation (e.g., “immigrant widows”) can affect the value of an individual’s relational resources, as well as their ability to use them to create capital (Anthias, 2012; Erel, 2010; Bastia, 2014). I propose that volunteering mitigates immigrants’ interrelated categories of disadvantage and creates an environment where they might access the resources they need to integrate. Furthermore, I suggest that newcomers minimize their outsider status by volunteering and building mutually reinforcing relationships with nonimmigrants (Russel and White, 2001). I summarize this path in Proposition 1.

Proposition 1 (P1): Immigrant volunteering alongside nonimmigrants can lead to mutual relationship-building within the host society.

Proposition 1 speaks to the interdependence developed when immigrants successfully build relationships with nonimmigrants through volunteering (Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). Social structures, such as volunteering networks, allow for the creation of mutual trust as a form of social credit (Coleman, 1988; Handy and Greenspan, 2009). The social capital that immigrants accrue consists of network-related phenomena such as information exchange, mutual obligations, consultation networks, and, ultimately, interdependence (Coleman, 1988; Luiz Coradini, 2010; Erel, 2010). Considering the duality of these actions, relationships between immigrants and nonimmigrants become reciprocal and mutually reinforcing (Coleman, 1988; Russell and White, 2001; Weisinger and Slipante, 2005). Furthermore, literature implies that social capital is also beneficial to those individuals who do not produce it (Coleman, 1988), which explains why immigrant volunteering is advantageous to nonimmigrants as well (Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019; Yap et al., 2010). For example, voluntary initiatives can better achieve minority-sensitive social change when immigrants join the volunteer force. Therefore, volunteer settings are generally more inclusive since client needs are prioritized over differences between volunteer group members (Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019; Russel and White, 2001).

Intersectionality can also be a powerful tool in creating inclusive spaces (Bailey, 2009; Daftary, 2020; Lu et al., 2001). This framework provides education for all groups in all settings, from the underserved to the wealthy and from immigrants to nonimmigrants (Anthias, 2014; Daftary, 2020; Kaushik and Walsh, 2018). Intersectionality can help individuals focus on commonalities rather than differences (Bailey, 2009; Harris and Leonardo, 2018; Lu et al., 2001) between immigrants and nonimmigrants. Individuals can apply intersectionality by building knowledge while remaining curious about both identity differences and shared commonalities (being volunteers), experiences (volunteering), and concerns (the needs of the clients) (Harris and Leonardo, 2018; Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). Through these commonalities, native-born volunteers may learn to understand and celebrate differences in the volunteer space and beyond. The direct cause of immigrant integration in the model connects to the consequences of building relationships with nonimmigrants. I summarize this path in proposition 2.

Proposition 2 (P2): Mutual relationship-building in the host society can create interdependence between immigrants and nonimmigrants.

In addition to the effects suggested in propositions 1 and 2, the model indicates that interdependence in the volunteer setting can lead to immigrant integration in the long term. As immigrants serve as volunteers and become integral to the organization structure, nonimmigrants may comprehend these individuals' true value and indispensability (Anthias, 2014; Björkman et al., 2007; Handy and Mook, 2011). Teamwork towards a common goal, such as solving societal issues, also creates bonds of attraction that unite immigrants and nonimmigrants beyond the voluntary settings (Anthias, 2014; Danso and Lum, 2013; Harris and Leonardo, 2018). As these two groups agree on a shared system of meaning (e.g., prioritizing the needs of the underserved), they experience Blau’s (2008) social integration. Immigrants thus work alongside nonimmigrants to improve the host society and showcase their talents and resourcefulness (Danso and Lum, 2013; Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Yap et al., 2010). Literature also reveals that nonimmigrant fears toward newcomers diminish when they regularly interact with immigrants in positive settings (Björkman et al., 2007; Oliver, 2010; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

This approach leverages intersectionality as a force for good. Instead of focusing on cultural differences, the host society should apply intersectionality to uncover inequalities adversely affecting immigrants. This approach allows the host society to move beyond biases to address struggles over resources, including social capital (Anthias, 2014; Eler, 2010; Harris and Leonardo, 2018). Voluntary settings are often safe places for dialogue between social identities, thus providing a basis focusing on marginality (e.g., social inequality) instead of immigrant status (e.g., green card holder) (Anthias, 2014; Oliver, 2010; Stasiulis et al., 2020). As immigrants proactively learn from nonimmigrants and vice versa, these interactions increase value (Danso and Lym, 2013; Garg, 2021; Oliver, 2010). Native-born volunteers may start to perceive immigrant talents and resourcefulness as indispensable to their mutual volunteer mission. Through shared experiences and an agreed-upon system of norms and values—such as assisting the recipients of the volunteer services—immigrants and nonimmigrants could recognize each other as essential on the road to shaping and improving the host society. I encapsulate this idea in proposition 3.

Proposition 3 (P3): Interdependence between immigrants and nonimmigrants can result in integration beyond the voluntary setting.

The following instructional figure depicts the model’s final path from immigrant volunteering to immigrant integration. This conceptual model shows external and internal factors that may impact the newcomer's trajectory from volunteering to integration.

Figure 2

Conceptual path from immigrant volunteering to immigrant integration

Discussion

I argue that this conceptual model’s sustainability is based on an ongoing win-win exchange between immigrants and nonimmigrants. Volunteering can be a tradable good or service to gain networks and resources from nonimmigrants, thereby enhancing immigrant integration (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Wand and Handy, 2014; Sinha et al., 2011). Conversely, nonimmigrants can strike a deal by partnering with newcomers as volunteers, thereby increasing the volunteer organization’s diversity and resourcefulness when addressing community needs (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Oliver, 2010). When immigrants volunteer, they can exchange their talents for resources and connections with nonimmigrant volunteers (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). In addition, research shows that immigrants often volunteer to improve their credentials (Sinha et al., 2011; Putnam, 2000; Weisinger and Salipante, 2005). For example, volunteering can provide newcomers with experience, knowledge, and skills to enhance their success in the job market (Baert and Vujić, 2016; Nakhaie and Kazemipur, 2013; Oliver, 2010).

As immigrants work alongside nonimmigrants, the repeated interactions build mutual trust. This trust, in turn, becomes a currency that immigrants can exchange for intangible goods, such as professional networks or personal relationships (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Putnam, 2000). By sharing voluntary tasks, immigrants learn skills ranging from the ability to navigate the system’s bureaucracy to gaining knowledge about the host country’s culture and social norms (Baert and Vujić, 2016; Nesbit, 2017). Nonimmigrants may grow in appreciation for immigrant volunteers and gain friendships that extend beyond professional interactions (Putnam, 2000; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

These types of trade between immigrants and nonimmigrants fall in line with social exchange theory. This paper suggests that at its most elemental level, immigrants offer their volunteer services in exchange for improved integration. On the other hand, nonimmigrants may offer their volunteer networks and resources for additional volunteer members. However, it must be noted that immigrants and nonimmigrants will articulate the costs and benefits of volunteer labor differently (Femida and Mook, 2011; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). Additionally, to recruit, manage and retain immigrant volunteers, the host society must understand the conceptual level of the costs and benefits of both perspectives. Social exchange theory allows us to examine immigrant volunteering from the viewpoint of both immigrants and nonimmigrants.

At the outset, I apply this theoretical framework with the assumption that for a win-win situation between immigrants and nonimmigrants, the benefits must exceed the costs for both groups (Cook, 2015; Jonason and Middleton, 2015; Stryker, 2001). Due to the subjective nature of the valuation of benefits and costs, both perspectives will remain conceptual while exploring the effects on intersectional social capital, trust, and networks.

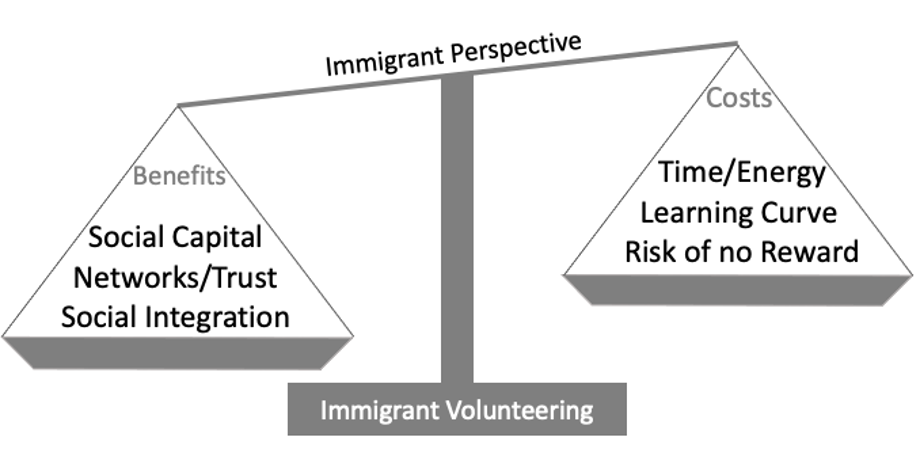

The Immigrant Perspective. The cost of volunteering to an immigrant can range from missed job income to direct expenses, such as a bus fare to the volunteer facility (Handy and Mook, 2011; Lee and Brudney, 2009). This might be too high of a cost for immigrants struggling to gain financial stability (Couton and Gaudet, 2008; Qvist, 2018). On the other hand - for those who can afford to put time and energy into the volunteer activity - a significant cost may also come about with the learning curve; From entering the volunteer system in a language foreign to their own, acclimatizing to the work environment, adopting unspoken norms and values, to studying the methods with which the volunteer services are implemented – technological or not – the learning curve can be perceived as too steep to climb (Couton and Gaudet, 2008; Qvist, 2018). On the other hand, even if the immigrants are willing to incur those costs, there is a chance that they will not reap a reward that is greater than their investment.

As per our conceptual framework theories (intersectionality, social capital, trust, social networks, social integration), immigrants may choose to risk the costs for the sake of reaping benefits accrued through volunteering. Depending on the volunteer function, immigrants may turn their intersectional characteristics into a strength and become a valuable “asset” to the volunteer organization. For instance, an Albanian immigrant,å familiar with both culture and traditions of the Balkan region, can help translate vital information for a nonprofit that alleviates food insecurities in underprivileged non-English-speaking families (Sali, 2021). This, in turn, creates a win-win exchange in social capital (Adongo et al., 2019; Drollinger, 2010; Lee and Brudney, 2009). The volunteer body gains a member with the unique skills necessary to serve the clients effectively, and the immigrant receives trust from their volunteer colleagues and a potential network with invaluable relational links (Adongo et al., 2019; Putnam, 2000). These network connections may help the immigrant overcome structural constraints such as the inability to get a job due to an uncertified degree (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). As these professional relationships blend into personal relationships, bonds of attraction start stabilizing among immigrants and nonimmigrants, thereby building a bridge toward social integration, where conflicts diminish and perceptions of connectedness grow (Björkman et al., 2007; Blau, 2008; Ruiz, Wang and Handy, 2021; Khvorostianov and Remennick, 2017).

Figure 3

The Immigrant Perspective: Costs and Benefits of Immigrant Volunteering

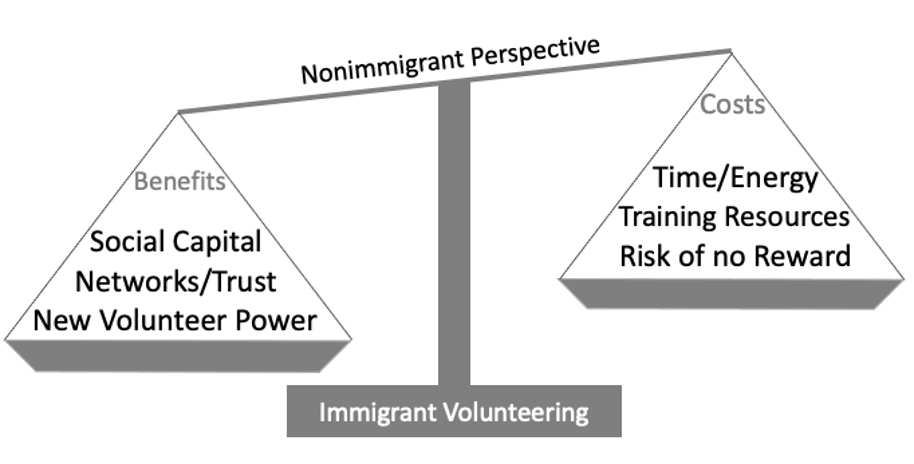

The Nonimmigrant Perspective. Nonimmigrants may measure the cost of immigrant volunteering differently than the immigrants themselves. For instance, nonimmigrant volunteers and volunteer managers may have to accommodate by investing additional time and energy in building efficient communication and teamwork with their immigrant peers (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). This may be perceived as a high cost, depending on how familiar immigrant volunteers are with the norms and values of the host society, the organizational culture, and even the language (Ruiz, Wang, and Handy, 2021; Wang and Handy, 2014). Similarly, accepting immigrant volunteers into an organization may require additional training resources, such as bilingual guideline pamphlets or training workshops catered to a specific culture (Lee et al., 2018; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019). Even if the nonimmigrant volunteer body decides to risk these “costs” for the sake of new members, there is a chance of no rewards due to, for instance, failed retention strategies leading to a loss of recruited immigrant volunteers (Lee et al., 2018).

On the other hand, by building genuine relationships with immigrant volunteers, the volunteer body can benefit from invaluable social capital exchanges that would not occur amongst nonimmigrants. For instance, if a nonprofit wishes to expand its voluntary services into ethnic neighborhoods, it will benefit from partnering with immigrants in the enclave. Moreover, as nonimmigrants build trust with immigrant volunteers, they expand organizational, professional, and personal networks into this population (Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

Therefore, immigrants’ intersecting characteristics, knowledge, experience, and skills can create multiple benefits for the volunteer body. By working with immigrants towards a common goal, nonimmigrants can share norms and values, build interpersonal trust, collaborate in the volunteer body’s mission, experience reciprocal exchanges of social capital, and share a sense of identity by supporting each other (Adongo et al., 2019; Drollinger, 2010). This type of relationship-building, in turn, creates trust-based social networks that lead to perceived and experienced social integration on the immigrant side and a sustainable, new volunteer force for nonimmigrant volunteer bodies (Lee et al., 2018; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019).

Figure 4

The Nonimmigrant Perspective: Costs and Benefits of Immigrant Volunteering

It must be noted that simple contact between immigrants and nonimmigrants may not necessarily build interracial understanding and integration; in some cases, it may even worsen racial tensions (Oliver, 2010; Pettigrew, 1998). However, voluntary settings are unique in that the members choose to participate out of their own free will and according to their preferences. Therefore, volunteer settings provide a space of repeated, positive interactions where immigrants and nonimmigrants proactively work on shared goals of their own choice, a common language, and equal status (National Academies Press, 2015; Oliver, 2010; Sinha, Greenspan, and Handy, 2011). Once immigrants and nonimmigrants partner to maximize each others’ benefits, the resulting interdependence can spill beyond the voluntary setting (Handy and Greenspan, 2009; Putnam, 2000). The ensuing immigrant-nonimmigrant relationships suggest that newcomers can engage in voluntary work to experience enhanced integration in the host country (Pettigrew, 1998; Ruiz Sportmann and Greenspan, 2019; Ruiz, Wang, and Handy, 2021).

Implications for the Study of Immigrant Volunteering and Integration

Understanding the influence of identity categories (e.g., immigrant status, ethnicity, gender, religion, etc.) in shaping immigrant integration is a highly complex task (Choo and Ferree, 2010; Kaushik and Walsh, 2018; Stasiulis et al., 2020). The challenge for research on immigrant volunteering and integration is the expectation of exploring various categories of difference simultaneously. It is pragmatically difficult to conduct intersectional studies accurately (Daftary, 2020; Cho et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2011). Due to the lack of consensus on intersectionality, the framework proves more helpful for marking ground for analysis than performing an analysis (Bailey, 2009; Harris and Leonardo, 2018; Stasiulis, Jinnah, and Rutherford, 2020). Bastia (2014) states that intersectionality as an approach offers only vague terminology and lacks a specific methodology. Additionally, it is mainly used by (feminist) researchers in the US and Europe, thus limiting its generalizability in other cultural locations (Choo and Feree, 2010; Hankivsky and Cormier, 2011; Lutz et al., 2011). When applying intersectionality to immigrant integration, researchers must communicate the context-specific meanings of gender, ethnicity, race, etc. (Bailey, 2009; Bastia, 2014; Davis, 2008). Intersectionality typically appears in qualitative research with smaller populations, again implying a possible lack of generalizability (Ravitch and Carl, 2019; Ravitch and Riggan, 2016). Therefore, I suggest that statistical explorations must find ways to include intersectionality into methodological approaches to longitudinal data on immigrants.

Following Cho et al. (2013), rather than dwelling on what intersectionality is, this conceptual paper focuses on what intersectionality does to enrich the understanding of integration. In line with Bastia (2014), intersectionality can open new inquiries into immigrant integration studies while maintaining a solid preoccupation with social equality. This paper shows that studies should draw from other theories that complement concepts already included in intersectionality (Daftary, 2020; Bailey, 2009; Garg, 2021; Hankivsky and Cormier, 2011; Lutz et al., 2011). I offer that an intersectional approach is necessary for immigrant integration research and its connection to civic participation. I also encourage researchers to study and promote volunteer settings that actively engage and partner with immigrants in a culturally informed way (Lee et al., 2018). Finally, researchers can apply intersectionality as a tool of analytic and political sensibility to understand interlinking sources of integration barriers so as to transform or abolish them (Daftary, 2020; Garg, 2021; Kaushik and Walsh, 2018; Stasiulis, Jinnah and Rutherford, 2020).

Additionally, future studies on immigrant volunteering should consider that immigrants may consciously or subconsciously subject themselves to the meta-discourse of the “good citizen” (Wilson-Forsberg and Sethi, 2015; Yap et al., 2010). Immigrants may feel pressured to volunteer in order to “fit in,” portraying themselves as autonomous to conveniently feed into the neo-liberalist, Western discourse (Kaushik and Walsh, 2018; Yap et al., 2010). Governments and policymakers may be tempted to promote integration strategies that shape vulnerable immigrants into “governable citizens.” Therefore, researchers should avoid exploring and promoting volunteering and other types of civic participation as political tools that create “good citizens” that are considered “worthy” of integration (Kaushik and Walsh, 2018; Wilson-Forsberg and Sethi, 2015; Yap et al., 2010). Academia should actively deconstruct any abuse of power by the host society (Manatschal and Stadelmann-Steffen, 2013). Instead, researchers should explore volunteering as a win-win situation that can help immigrants and nonimmigrants create mutual benefits —which is why social exchange theory was chosen for this analysis.

The lack of social theories in immigrant volunteering calls for an exploration of relevant theoretical approaches and a rediscovery of those theories implicitly mentioned in related research. The use of theory will not necessarily result in methodological changes. What limited research exists already presents a wide range of relevant quantitative and qualitative methodologies in the field of immigrant volunteering. The addition of theory will allow researchers to conduct their investigations from an academically informed place, thus simplifying the weeding out of weak or faulty assumptions and hypotheses on immigrant integration. Social theory insights expand the body of knowledge by interpreting immigrant volunteering and its implications for immigrants as a more comprehensive endeavor.

Conclusion

This study explores whether immigrant volunteering can act as a conduit for immigrants’ social integration into their host society. Using a conceptual approach, I examine Bourdieu’s theory on social capital, Coleman’s theory on trust and social networks, and Blau’s theory on social integration. While these social theories help explain why volunteering may lead to enhanced integration, they do not account for the disadvantages newcomers face when settling into the host country. By applying an intersectional approach, I emphasize the limitations our model might face. I also explore immigrant volunteering from a social exchange perspective to elucidate how newcomers might engage in voluntary services in exchange for improved integration. By creating a win-win situation for immigrants and nonimmigrants, immigrant integration can succeed in the voluntary setting and positively influence spillover effects that may lead to integration-related advancement outside the realm of volunteering.

Adongo, R., (Sam) Kim, S., & Elliot, S. (2019). “Give and take”: A social exchange perspective on festival stakeholder relations. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.005

Anthias, F. (2012). Transnational mobilities, migration research and intersectionality. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 2(2), 102–110. http://doi.org/10.2478/v10202-011-0032-y

Baert, S., & Vujić, S. (2016). Immigrant volunteering: A way out of labour market discrimination? Economics Letters, 146, 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2016.07.035

Bailey, A. (2009). On intersectionality, empathy, and feminist solidarity: A reply to Naomi Zack. Journal for Peace and Justice Studies, 19(1), 14–36. https://doi.org/10.5840/peacejustice200919116

Bastia, T. (2014). Intersectionality, migration and development. Progress in Development Studies, 14(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1464993414521330

Björkman, I., Stahl, G. K., & Vaara, E. (2007). Cultural differences and capability transfer in cross-border acquisitions: The mediating roles of capability complementarity, absorptive capacity, and social integration. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 658–672. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400287

Blau, P.M. (2008). Exchange and power in social life. Transaction. [Originally published 1964].

Bourdieu, P. (2001). The forms of capital. In M. Granovetter & R. Swedberg (Eds), The sociology of economic life (2nd ed.) (pp. 96–111). Westview.

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. https://doi.org/10.1086/669608

Choo, H. Y., & Ferree, M. M. (2010). Practicing intersectionality in sociological research: A critical analysis of inclusions, interactions, and institutions in the study of inequalities. Sociological Theory, 28(2), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-9558.2010.01370.x

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

Cook, K. S. (2015). Exchange: Social. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 482–488). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.32056-6

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0486

Couton, P., & Gaudet, S. (2008). Rethinking social participation: The case of immigrants in Canada. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l'integration et de la migration internationale, 9(1), 21-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12134-008-0046-z

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Daftary, A. (2020). Critical race theory: An effective framework for social work research. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 29(6), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1534223

Dahinden, J. (2013). Cities, migrant incorporation, and ethnicity: A network perspective on boundary work. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 14(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12134-011-0224-2

Danso, K., & Lum, T. (2013). Intergroup relations and predictors of immigrant experience. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 22(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2013.756733

Davis, K. (2008). Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist theory, 9(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1464700108086364

Drollinger, T. (2010). A Theoretical Examination of Giving and Volunteering Utilizing Resource Exchange Theory. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 22(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495140903190416

Duran, A., & Jones, S. R. (2020). Intersectionality. In Z. A. Casey (Ed.), Encyclopedia of critical whiteness studies in education (pp. 310–320). Brill Sense.

Erel, U. (2010). Migrating cultural capital: Bourdieu in migration studies. Sociology, 44(4), 642–660. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0038038510369363

Esses, V. M., & Abelson, D. E. (Eds.). (2017). Twenty-first-century immigration to North America: Newcomers in turbulent times. McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

Garg, R. (2021). Conceptualizing (Immigrant) Parents as Knowledgeable Adults in Their Children's Lives. Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education, 18(2), n2.

Gilson, L. L., & Goldberg, C. B. (2015). Editors' comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group & Organizational Management, 40(2), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1059601115576425

Handy, F., & Greenspan, I. (2009). Immigrant volunteering: A stepping stone to integration? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(6), 956–982. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0899764008324455

Handy, F., & Mook, L. (2011). Volunteering and volunteers: Benefit-cost analyses. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(4), 412-420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731510386625

Hankivsky, O., & Cormier, R. (2011). Intersectionality and public policy: Some lessons from existing models. Political Research Quarterly, 64(1), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1065912910376385

Harder, N., Figueroa, L., Gillum, R. M., Hangartner, D., Laitin, D. D., & Hainmueller, J. (2018). Multidimensional measure of immigrant integration. PNAS, 115(45), 11483–11488. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808793115

Harris, A., & Leonardo, Z. (2018). Intersectionality, race-gender subordination, and education. Review of Research in Education, 42(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0091732X18759071

Jonason, P. K., & Middleton, J. P. (2015). Dark Triad: The “Dark Side” of Human Personality. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 671–675). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.25051-4

Kaushik, V., & Walsh, C. A. (2018). A critical analysis of the use of intersectionality theory to understand the settlement and integration needs of skilled immigrants to Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 50(3), 27–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/ces.2018.0021

Khvorostianov, N., & Remennick, L. (2017). ‘By helping others, we helped ourselves: ’volunteering and social integration of ex-soviet immigrants in Israel. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(1), 335-357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9745-9

Kunz, J. L. (2003). Social capital: A key dimension of immigrant integration. Canadian Issues. 2003, 33–34.

Lee, S. H., Johnson, K. J., & Lyu, J. (2018). Volunteering among first-generation Asian ethnic groups residing in California. Journal of cross-cultural gerontology, 33(4), 369-385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-018-9358-4

Lee, Y. J., & Brudney, J. L. (2009). Rational volunteering: a benefit‐cost approach. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330910986298

Lu, Y. E., Lum, D., & Chen, S. (2001). Cultural competency and achieving styles in clinical social work: A conceptual and empirical exploration. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 9(3–4), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J051v09n03_01

Luiz Coradini, O. (2010). The divergences between Bourdieu’s and Coleman’s notions of social capital and their epistemological limits. Social Science Information, 49(4), 563–583. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0539018410377130

Lutz, H., Vivar, M. T. H., & Supik, L. (2011). Framing intersectionality: An introduction. In H. Lutz, M. T. Herrera, & L. Supik (Eds.), Framing intersectionality: Debates on a multi-faceted concept in gender studies (pp. 1–22).

Manatschal, A., & Stadelmann-Steffen, I. (2014). Do Integration Policies Affect Immigrants' Voluntary Engagement? An Exploration at Switzerland's Subnational Level. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(3), 404-423. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.830496

Marek, M. (2015). Conceptual Manuscript Outline [Class Handout]. Communication Arts, Wayne State College, Wayne, Nebraska. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4962.5768/1

McGregor, S. (2018). Conceptual and theoretical papers. In Understanding and evaluating research (pp. 497-528). SAGE Publications, Inc, https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781071802656

Nakhaie, M. R., & Kazemipur, A. (2013). Social capital, employment and occupational status of the new immigrants in Canada. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 14(3), 419–437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0248-2

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, & Committee on Population. (2016). The integration of immigrants into American society. National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/read/21746/chapter/1

Nesbit, R. (2017). Advocacy recruits: Demographic predictors of volunteering for advocacy-related organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(3), 958–987. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11266-017-9855-z

Oliver, J. E. (2010). The paradoxes of integration: Race, neighborhood, and civic life in multiethnic America. University of Chicago Press.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In L. Crothers & C. Lockhart (Eds.), Culture and politics: A reader (pp. 223–234). Palgrave Macmillan.

Qvist, H. P. Y. (2018). Secular and religious volunteering among immigrants and natives in Denmark. Acta Sociologica, 61(2), 202-218. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0001699317717320

Ravitch, S. M., & Carl, N. M. (2019). Qualitative research: Bridging the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological. Sage Publications.

Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2016). Reason and rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research. Sage Publications.

Raza, M., Beaujot, R., & Woldemicael, G. (2013). Social capital and economic integration of visible minority immigrants in Canada. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 14(2), 263–285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0239-3

Ruiz Sportmann, A. S., & Greenspan, I. (2019). Relational interactions between immigrant and native-born volunteers: Trust-building and integration or suspicion and conflict? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(5), 932–946. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00108-5

Ruiz, A. S., Wang, L., & Handy, F. (2021). Integration and volunteering: The case of first-generation immigrants to Canada. Voluntary Sector Review. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080521X16319931902392

Russell, M. N., & White, B. (2001). Practice with immigrants and refugees: Social worker and client perspectives. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 9(3–4), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1300/J051v09n03_04

Sali, J. (2021). My Covid Experience in the Age of Technology. Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education. Retrieved from https://urbanedjournal.gse.upenn.edu/archive/volume-18-issue-1-fall-2020/my-covid-experience-age-technology

Sinha, J. W., Greenspan, I., & Handy, F. (2011). Volunteering and civic participation among immigrant members of ethnic congregations: Complementary not competitive. Journal of Civil Society, 7(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2011.553409

Sobel, J. (2002). Can we trust social capital? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(1), 139–154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/0022051027001

Stasiulis, D., Jinnah, Z., & Rutherford, B. (2020). Migration, intersectionality and social justice (guest editors’ introduction). Studies in Social Justice, 2020(14), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v2020i14.2445

Stryker, S. (2001). Social Psychology, Sociological. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 14409–14413). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01963-X

Wang, L., & Handy, F. (2014). Religious and secular voluntary participation by immigrants in Canada: How trust and social networks affect decision to participate. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25(6), 1559–1582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9428-8

Weick, K. E. (1989). Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Academy of management review, 14(4), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/258556

Weisinger, J. Y., & Salipante, P. F. (2005). A grounded theory for building ethnically bridging social capital in voluntary organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 34(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0899764004270069

Wilson-Forsberg, S., & Sethi, B. (2015). The volunteering dogma and Canadian work experience: Do recent immigrants volunteer voluntarily? Canadian Ethnic Studies, 47(3), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1353/CES.2015.0034

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual review of sociology, 26(1), 215-240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215

Yap, S. Y., Byrne, A., & Davidson, S. (2011). From refugee to good citizen: A discourse analysis of volunteering. Journal of Refugee Studies, 24(1), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feq036

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 79.75 KB | |

| 206.34 KB | |

| 85.34 KB | |

| 84.03 KB |