It’s Not Indoctrination, It’s Criticality: Using Curriculum to Explore Complex Ideas Around Race and Social Justice

This article addresses the challenges and importance of integrating discussions on race and social justice into the classroom. Considering recent legislative actions in various states aimed at restricting such discussions, the article presents an empowering framework designed to support educators in facilitating these conversations. This framework, rooted in culturally responsive pedagogy, offers practical tools and guiding questions to help teachers create an environment that encourages inquiry and exploration of racial complexities without imposing personal viewpoints. The framework aims to move beyond simply identifying disparities to examining systems of oppression and encouraging students to take action. Feedback from teachers who implemented this framework shows significant improvements in their comfort and proficiency in discussing racial issues with students, instilling a sense of confidence and capability. The article also highlights the importance of self-reflection and continuous learning for teachers to lead these conversations effectively. It underscores the need for educators to develop strategies that allow students to engage critically with racial topics and employ counter-narratives to challenge discriminatory rhetoric. In conclusion, the article calls for a concerted effort in teacher education to counteract the resistance to racial equity discussions.

Introduction

On May 12, 2023, a teacher in Florida was under investigation for showing the movie Strange World. The plot involves a father and son exploring their relationship while attempting to save the world. Sounds harmless, right? Well, the act of showing the film violated Florida’s “anti-woke” and “don’t say gay” legislation, as the film features a bi-racial character with a Black mother and White father who also identifies as gay. Unfortunately, this suppression of diverse content continues to become the norm as America leans further and further into its white supremacy roots. Educators currently face uncertainty and fear about what they can say when teaching and discussing race and racism in the classroom because of recent legislation that 35 states have passed or proposed. Such legislation silences teachers' speech on race and attempts to ban books written by Black authors or about people of color (Alfonseca, 2022; American Library Association, 2021).

Supplementing the literacy curriculum requires educators to deeply understand the curriculum, learning processes, social environment, and literature. These choices also require the teacher to take risks since they diverge from the predefined curriculum and explore subjects and ideas that might alter the conventional curriculum (Flores et al., 2019). Teachers must provide opportunities for student discussions that lead to understanding the complexity of race and racism (Price-Dennis & Sealey-Ruiz, 2021). Teachers must actively engage students in critical conversations and be alert to the emergence of racist beliefs in discussions and texts (Sealey-Ruiz, 2021).

Few examples exist of racialized discussions that provide specific guidance for teachers on how to use facilitation tactics to enhance their students' racial literacy. We introduce a novel framework that supports educators in engaging in discussions about race and racism, with literature as a focal point. Furthermore, we provide evidence of how this framework develops teachers' capabilities and expertise while also improving classroom instructional practices, specifically in the area of academic discourse.

The Framework

During a recent coaching conversation, a teacher expressed that he received significant pushback from parents when students read All American Boys (Reynolds & Kiely, 2017). This novel tells the story of two teenage male friends, one Black and the other White, and how their everyday experiences based on race differ, particularly around policing. The teacher taught this unit in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. This teacher shared that he explicitly attempted to have students appreciate the problems within police departments as institutions and their role in communities of color. This teacher sought to provide a vehicle for his students to explore and discuss racial complexities without teaching a personal viewpoint, as often happens with traditional class lectures. The aim of this article is to encourage teachers to consider how they can avoid coming across as didactic and instead create opportunities for inquiry and investigation.

Our goal is to establish a pedagogical environment where teachers can comfortably engage in reflective discussions about race and its impact on their educational efforts. We envision a society in which individuals feel at ease discussing racial and identity-related issues in order to examine and take action toward dismantling oppressive systems. We encourage teachers to embrace the guiding question: How can I create an environment for my students to explore intricate subjects about race and identity without imposing my viewpoints?

Teachers should begin with a thematic unit plan that links all learning to a central topic and provides students with the opportunity to investigate, research, and engage in project-based learning experiences. We created a curriculum framework for teachers using the premises of Gholdy Muhammad's book Cultivating Genius (2020) and the original pillars of Gloria Ladson-Billings' culturally relevant pedagogy (2009). The framework provides teachers with comprehension and discussion questions that enhance students' grasp of the texts while simultaneously tackling equity concerns. The objective is to surpass the mere identification of disparities and instead delve into the examination of systems of oppression. McAnuff Gumbs articulates that “teachers might need support in ways of digging beyond surface levels to foster conversation that allows students to exert resilience and openness when confronted with their bias and the biases of others.” (2020, p. 112). This framework assists educators by offering explicit resources to enhance their understanding of racial literacy and enable instruction in their classrooms. Without a toolkit of resources, teachers might assume that they can engage in culturally responsive teaching simply by presenting texts that raise race or social justice issues. We laud any desire to foster cultural competence within classrooms; however, a more structured and intentional approach is crucial to truly shifting classrooms away from historically white-dominant learning spaces and mindsets (Okun, 2021).

Table 1 provides guiding questions for teachers to use in designing culturally responsive unit plans.

Table 1. Guiding Questions for Unit Plan Design

|

Identify Unit Objectives |

Determine Acceptable Evidence |

Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction |

Social Justice and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) |

|

Consider the plot and characters' experiences in the chosen text.

|

Identify a text-based call to action.

|

Center performance tasks and daily objectives on the novel's themes in addition to academic skills.

|

Note evidence and real-world scenarios that speak to the ideas being explored in the text.

|

As discussed in the next portion of this article, there is a profound impact on student learning when teachers have an obvious structure to be reflective and intentional when planning their instruction on race and racism.

Teacher learnings and feedback on the framework

Several New York City schools received literacy units developed through this framework, which were provided to kindergarten through 6th-grade teachers in spring 2023. During twelve weeks, students completed tasks that provided opportunities for learning demonstrations beyond the usual modes of assessment, such as the three-paragraph essay. According to Rudine Sims Bishop's (1990) research on multicultural children's literature, children should have the chance to see themselves in stories and literary curricula, learn about other people, and experience life from another's perspective. These units included culturally responsive texts that showcased various authentic lived experiences, highlighting students' identities (mirrors), and offering insights into the experiences of others (windows and sliding glass doors). These units also specified the expected results as performance tasks or student projects, provided concrete sample evidence of learning that teachers could gather, and addressed complex issues like gentrification, standards of beauty, and colorism.

To support instruction, the organization in this framework offered teachers guiding questions for facilitating classroom discussions. Teachers received resources and prompts to support their instructional decisions and create an environment where students could listen to these stories, participate, and synthesize the novels. This included tools to help children respond to racist concepts and deeply address social justice issues. There were examples provided of moves teachers could make during discussions. For example, adding to a student’s comments, rephrasing a student’s comments, correcting student misconceptions, and highlighting information within texts that diverge from the dominant ideology. This framework also offered teachers resources to deepen their understanding of race and help them teach children essential, racialized knowledge to build criticality.

It is important to emphasize that we should encourage teachers not to impose their personal opinions on students. Instead, they should allow students to examine racism and social justice-related ideas in literature through purposeful investigation. The aim is for educators to impart to their students the notion that the world is still developing, that favorable transformation is attainable, and that they possess the capability to initiate action. Teachers can facilitate educational transformation. Teachers, as public intellectuals, can offer a thorough theoretical examination of the technocratic and instrumental ideologies that underpin educational ideas outside of the process of conceiving, organizing, and creating curricula (Giroux, 2013).

Using various books as a springboard for racialized discussions, rather than downplaying or silencing the social justice topic of each text, these teachers encouraged their students to discuss the racial systemic structures that formed the foundation of each book. These units were intersectional, layered, and recursive. According to teachers, the application of these units of study increased:

- student exposure to various cultures, lived experiences, and perspectives

- students’ sense of agency to act, and

- forums for discussions on systematic racism and preconceived notions.

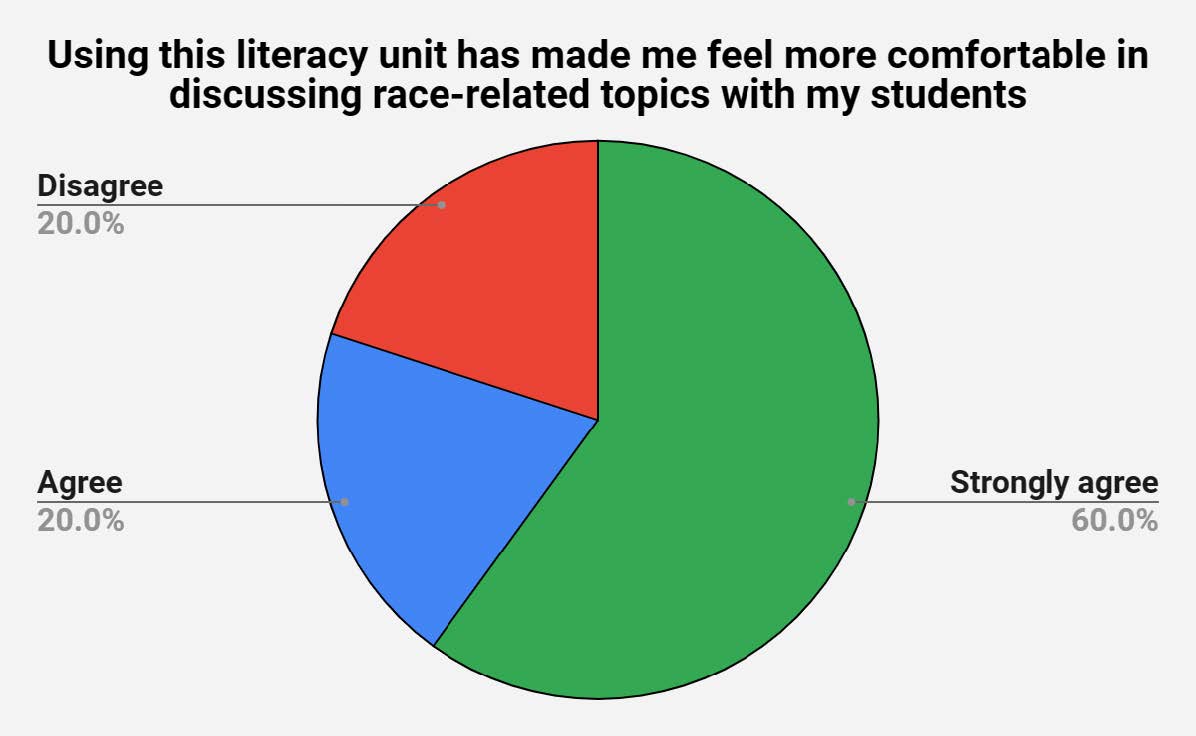

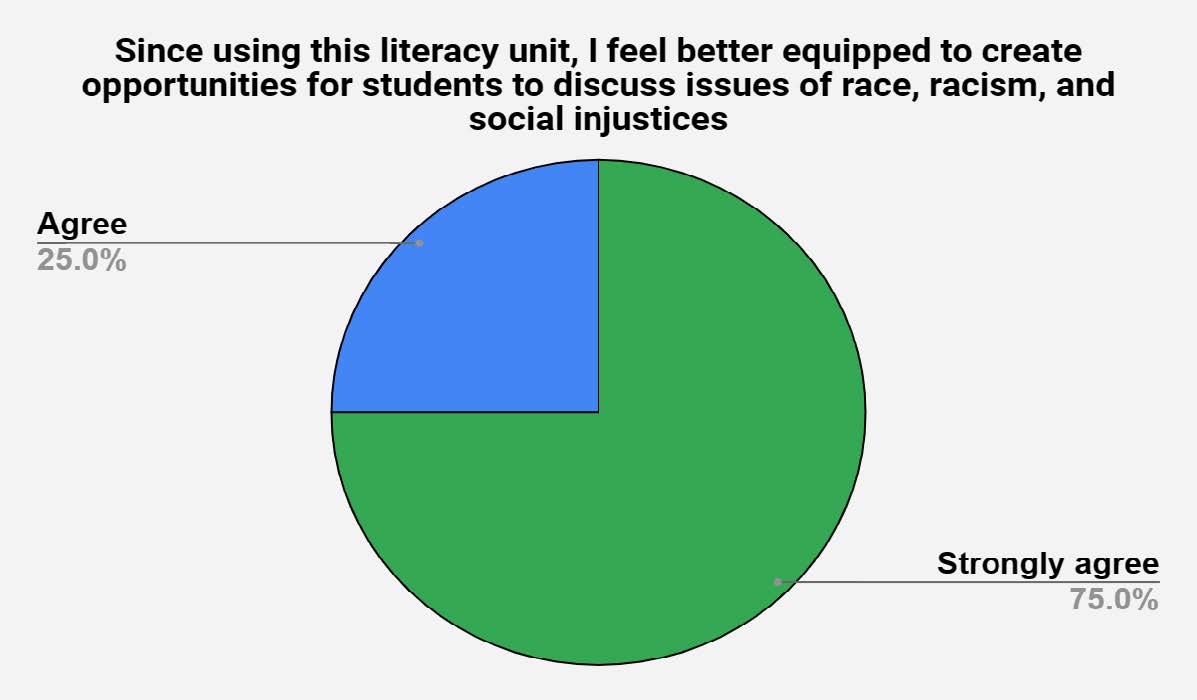

Figure 1 demonstrates that 80% of teachers felt more at ease talking about racial issues with their students after using this framework. Figure 2 shows that 75% of teachers strongly agreed that they are now better equipped to include discussions of social justice, racism, and racial issues in their lessons after their experience with our framework.

FIGURE 1:

Percentage of teachers feeling more comfortable having race conversations with students

FIGURE 2:

Percentage of teachers feeling better equipped to incorporate issues of race

The research presented in Figures 1 and 2 offers evidence of the efficacy of this particular framework in improving teachers' assurance and proficiency in dealing with racial matters in their classrooms. The data presented in Figure 1 shows that 80% of teachers feel more at ease discussing racial topics with their students. Figure 2 demonstrates that 75% of teachers feel more confident incorporating discussions of social justice, racism, and racial issues into their curriculum. These findings highlight the significant impact of the framework on bringing about positive change. These findings show that providing educators with a well-defined and explicit method to examine these crucial subjects promotes more effective communication and cultivates a more inclusive and empathetic classroom. The framework functions as a tool to equip teachers to facilitate difficult, complex, and sometimes uncomfortable discussions about race and racism, ultimately enhancing empathy and awareness in the educational environment.

Implications for Research

The ability to lead literature-based discussions or dialogical pedagogy that allows students to learn and discuss the impact of racism on their lives is difficult for many teachers. Many feel unprepared for having difficult, critical dialogues on race with their students, and some feel uncomfortable guiding discussions on subjects they don't fully understand or have not shared similar lived experiences (Milner, 2017). It may be easier—and more comfortable—to guide discussions away from talking about race and toward other identity-related topics, such as gender or socioeconomic status. Teachers must become familiar with strategies that reframe discussions of race while examining the intersectionality of identity so they can offer meaningful opportunities for students to engage.

For robust race-oriented conversations, teachers must engage in self-work to unpack their understanding of race as it manifests in their daily lives. Teachers must learn new strategies for assisting students in listening to, engaging in, and analyzing racial conversations. Such strategies include opportunities for their students to listen to stories, participate, and synthesize the narratives offered in literacy studies. Teachers also need to improve their ability to assist students in using counter-narratives to confront racist and discriminatory rhetoric. Additionally, teachers need guidance and coaching in order to help their students acquire critical race knowledge.

Conclusion

In the wake of worldwide demonstrations for Black Lives, efforts to achieve greater racial equity are encountering resistance and violence throughout the United States. Recent events demonstrate how discussions about race and racism are difficult to tolerate for many who choose to outlaw books that discuss racism, stifle equity reforms by demonizing critical race theory, and put pressure on school districts to fire educators or other teachers who they believe are indoctrinating students into pro-justice ideologies (Morgan, 2022). Those of us who are involved in teacher education must counteract these tactics. The geopolitical facts of 2024 make it essential for children to talk about race and understand how race affects their schools, communities, and homes. These discussions are best had within their classrooms when their teachers are well-equipped to facilitate them.

Alfonseca, K. (2022, March 24). Map: Where anti-critical race theory efforts have reached. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/map-anti-critical-race-theory-efforts-reached/story?id=83619715

American Library Association. (2021, November 29). ALA statement on book censorship: The American Library Association opposes widespread efforts to censor books in U.S. schools and libraries. https://tinyurl.com/dxcx7bpk

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Family Planning Perspectives, 6(3).

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), Article 8. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Flores, T. T., Vlach, S. K., & Lammert, C. (2019). The role of children’s literature in cultivating preservice teachers as transformative intellectuals: A literature review. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 214-232. doi.org/10.1177/1086296X19839181

Giroux, H. A. (2013). Neoliberalism’s War Against Teachers in Dark Times. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 13(6), 458–468. https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.1177/1532708613503769

Hall, D., & Nguyen, Q. (Directors). (2022). Strange world [Film]. Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children. Wiley.

McAnuff Gumbs, M. (2020, Spring). A multiple case study of the diversity richness of seven early literacy classrooms in upstate New York. Journal of Negro Education, 89(2), 97-121. https://muse-jhu-edu.proxy.library.upenn.edu/article/802531/pdf

Milner, H. R. (2017). Race, talk, opportunity gaps, and curriculum shifts in (teacher) education. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 66(1), 73–94. doi.org/10.1177/ 2381336917718804

Morgan, H. (2022). Resisting the movement to ban critical race theory from schools. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 95(1), 35–41. doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2021.2025023

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic.

Okun, T. (2021, May). White supremacy culture – still here. Dismantling Racism. https://www.dismantlingracism.org/uploads/4/3/5/7/43579015/white_supremacy_culture_-_still_here.pdf

Price-Dennis, D., & Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2021). Advancing racial literacies in teacher education: Activism for equity in digital spaces. Teachers College Press.

Reynolds, J., & Kiely, B. (2017). All American boys. Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books.

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2021). The critical literacy of race: Toward racial literacy in urban teacher education. In H. R. Milner IV & K. Lomotey (Eds.), Handbook of Urban Education (2nd ed., pp. 281–295). Routledge.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 54.19 KB | |

| 48.23 KB |