Placed-Based Teaching and Learning: History Lessons that Liberate Learning and Build Community Outside of the Classroom

Place-based learning encourages students to explore their local communities, learn about history, and develop critical thinking skills. This article uses counter-narrative to focus on six middle school students who participated in a History Club and entered the National History Day competition and discovered how history and place liberates learning and builds community.

Key words: place-based teaching, history, historical empathy, project based learning, community engagement, field trips

At the intersection of history and place are opportunities to disrupt the written curriculum and engage in immersive experiences that enlighten and inspire students to think critically. As a middle school history teacher, I am focused on decentering dominant narratives by engaging in place-based instruction that demonstrates the connectedness of a community to the people and the place. This article focuses on the six students in grades 7&8 who participated in a place-based History Club in the 2022-2023 school year. I drew on the insights of Paulo Freire’s liberation framework and the phenomenology of place to inform my instructional practice. What does place-based education look like in a history classroom? This article offers an example for (re)imagining history instruction by centering the pedagogical approach around place and space. Teaching history through the lens of “place” suggests that place-based instruction liberates learning by developing critical thinkers who have more agency over their learning. This article is a personal narrative of classroom discovery that serves as an entry point for conversations around place-based education in history classrooms.

My instructional approach to teaching and learning is immersive and student centered. Gruenewald (2003) defined pedagogy of place as “pedagogy that aims to contribute to the production of educational discourses and practices that explicitly examine the place-specific nexus between environment, culture, and education” (p.10). Designing immersive learning experiences forces students to find answers outside of the four walls of the classroom. Place-based learning is about getting kids out of the classroom and into the world.

It became clear to me that history is not always written in a book when I met Dr. George Blair at the New York Riding Academy on Randall's Island. Dr. Blair was an older African-American man who had photographs of the Harlem Rodeo displayed in his trailer that doubled as his office. I learned how to ride and care for horses all the while learning the history of Black Cowboys in America. I didn't expect this week-long professional development experience in the early part of my career to influence my practice as an educator, however, it was the person to person intimacy, storytelling, and the autonomy to gain new knowledge that made clear the potential of place-based history to be liberating intellectually and personally.

To be an effective teacher, you have to know how to care for your students and meet their needs (Anderson, 2020). Many of the students in my care are from various cultural backgrounds. It was important to show the students how their voices and stories are embedded in the local community. Approaching the district and building administrators about adding place-based components to the history curriculum, required preparing a list of responses that answered valid school policy and procedural concerns. With a spreadsheet in hand, I provided the cost per trip, location of trips, consent forms, medical clearances from the school nurse, the content areas that the trips aligned with, and funds needed for art supplies, school buses and competition application fees. Although budgets are created months before the school year starts, the administrators were flexible enough to provide some support for a place-based program. Additional support for this endeavor came from parents and teachers who volunteered to chaperone, fundraise, and assist with expenses for a competition where students' explored and researched the Dutch, Native, and African histories of their north Jersey neighborhood.

The inaugural launch of The History Club was a labor of love. To ensure that the students got the full immersive experience outside of the regular school day took extensive planning. The students self selected to be a part of the club and committed to showing up before school, during recess, and after school to learn. They buzzed with excitement and conversation each time we met. Our first walking trip on a cold November morning was about two miles from our school. When we arrived at Old Bergen Church, the pastor greeted us at the door and walked us to a room that had old photographs on the wall, a replica of the church, and various artifacts written in Dutch positioned around the room in glass display cases and some in book cases. (Fig. 1) At the end of the presentation and tour, the pastor invited the students to the cellar of the church. The cellar was a brightly lit room with exposed brick walls and sawdust floor with a small passageway at the far end. The pastor explained that the passageway was used to transport coffins from the church to the cemetery across the street. He went on to explain that the tunnel was most likely used to help African Americans along their journey to freedom since the cemetery was just a few short blocks away from the home of abolitionist David L. Holden. (Fig. 2)

The profound nature of this new information was not lost on the students. It gave the students a new perspective of a church that they had walked past frequently and didn’t know the significance it played in history. Learning about helpers and heroes who were not readily found in their history books motivated the students to make more discoveries and connections on their own. Several more walking trips enhanced the learning. Our group visited the monument of Peter Stuyvesant, who was a Dutch colonial governor. We toured PS 11, a historical site where the first free public school in north Jersey was built. The students met with historians at The Apple Tree House, a national historic landmark built in 1740. The head librarian in the special collections room at the local Public Library shared historical documents and artifacts with the students dating back to the 1800’s. (Fig. 3) Visiting each location uncovered new information and primary source documents that were instrumental to the students’ learning.

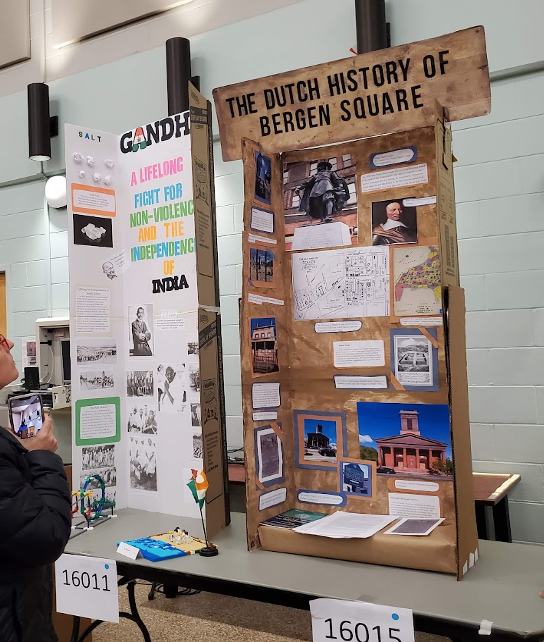

Exposing students to history in this way sparked curiosity and the desire to share what they learned. The students' writing skills and critical thinking skills grew exponentially over the course of several months as evidenced by the project and research paper they entered into the National History Day (NHD) competition.(Fig. 4) NHD, which is a project-based academic competition where students are able to present their findings of a topic of choice related to a theme through papers, exhibits, performances, documentaries, or websites. Students from all over the state compete. The inaugural History Club entered the National History Day competition in the spring of 2023.

Making meaning of the people, places, and spaces in the community can be challenging but also very rewarding. Academic excellence requires that teachers and students take the time to immerse themselves in history that is all around them. When given the academic tools, instructional support, and space to learn and think critically, students are capable of accomplishing amazing things. Combining place based instruction with history improved student writing, academic engagement, and comprehension skills. They developed friendships and most importantly they realized the story of their community included stories of resistance and resilience that stretched further back than they could have imagined. Learning history in places and spaces in the community gave them a lens to see themselves and the contributions of others clearly.

Appendix A

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Anderson, T. C. (2020). Academics, achievement gap, and nutritional health: The impact of Coronavirus on education. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 87(1).

Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher, 32(4), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032004003

Gruenewald, D. A. (2003a). Foundations of place: A multidisciplinary framework for place-conscious education. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 619–654. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040003619

Ladson-Billings, G.(1995) Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32, (3),p. 465-491

Vavrus, M. (2008). Culturally responsive teaching. 21st century education: A reference handbook, 2(49-57).

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 422.28 KB | |

| 435.79 KB | |

| 445.19 KB | |

| 618.44 KB |