Some of Your Students Are Trans: Administrative Sticking Points for Trans & Nonbinary High Schoolers in the School District of Philadelphia

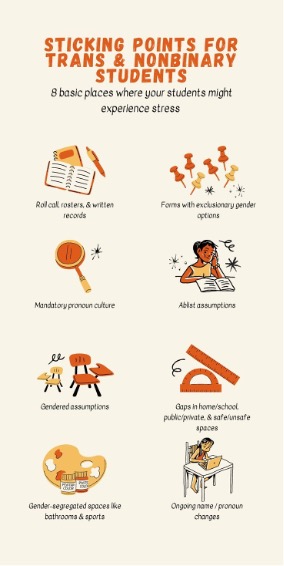

This article examines the administrative and bureaucratic barriers faced by trans and nonbinary high-school students in the School District of Philadelphia. Despite strong gender-inclusive policies like the district’s Policy 252, student interviews, first-hand observation, and document analysis reveal a variety of stress points that trans and nonbinary students still regularly face. This paper explores those “sticking points” individually and in detail through student experiences, from name and pronoun changes to bathrooms and written records, encouraging greater awareness among classroom teachers and school staff. Ultimately, the persistence of student challenges even amidst supportive policy - itself far from a guarantee in many school districts - suggests that gender inclusivity is not subject to single solutions, but rather requires care-filled consideration of stress points in our own distinct and ever-evolving contexts.

Introduction

On the first day of school, a 9th-grade boy with long braids, a flat-brimmed hat, and an impressive ability to find a slouch from any position, sitting or standing, wandered into my classroom and slumped into a chair while I was eating lunch.

“Yo, can I charge my phone?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said. As he plugged his charger into the nearest powerstrip, I asked, “How’s your first day of school going?”

“Awful.”

“Ah, I’m sorry to hear that. What’s up?”

“Kids, man. You know how it is.”

I laughed a little at this and asked, “What’s your name?”

“You mean my real name or my deadname?” he replied, his eyes sharpening out of their practiced unfocus as he looked up at me.

Othello had come out as trans in the year and a half of online schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now that he was back in school, he had run up against an administrative barrier to that identity: his deadname was still in the district computer system and, therefore, on the rosters that teachers called roll from. Teachers had been calling it out all day, and some students had apparently followed suit - hence the exhausted demeanor.

Othello’s situation, which ultimately involved chasing down counselors and principals, navigating ever-changing Google Forms, and fending off well-meaning but dangerous privacy breaches, is just the first of several that I’ll touch on in my inquiry portfolio, each elucidating the sorts of snags students are prone to encounter while exploring, transitioning, or simply expressing their gender identities in school.

The School District of Philadelphia is arguably one of the most progressive in the nation in terms of protections for trans and nonbinary students, and many teachers in the district are allied to that initiative. What I’m interested in investigating here is by no means a series of shortcomings on the part of staff, infrastructure, school administration, or even district policy. Rather, I want to shed light on the difficulties that arise when navigating nontraditional gender identities in environments where administrative and bureaucratic concerns preside. For some of these difficulties, I may be able to suggest antidotes. But what matters more is that educators bear in mind where these potentially tricky points lie so that they can navigate them in their own contexts with consideration of their own students.

Take Othello’s case. In the lunchroom, on the bus, at the Wawa, and in most parts of life, trans students are unlikely to be deadnamed (that is, called by the name they used before transitioning) by strangers, simply by virtue of the fact that strangers have to ask one’s name in the first place. In the classroom, on the other hand, students are hailed by their legal names. As subjects of the state and citizens of bureaucracy, the onus is on them to make the correction through the means – often imperfect – provided by that bureaucracy.

Several actions followed from that first day of school.

First, trans and nonbinary students were problematized, albeit benevolently, as administrative issues that needed special tracking. School administration began to circulate a live Google Doc entitled “[School] 2021-2022 Transgender Students,” containing a running list of trans and gender-nonconforming students in the format, “[Deadname] is now [Name] and uses [pronouns],” or “[Deadname] goes by [Name] and uses [pronouns].”

Secondly, the administration made a concerted effort to correct students’ names in the rosters.

Thirdly, I decided to make a point of providing a safe space for trans and nonbinary students within my classroom. I did this through a start-of-class survey as well as through personal, one-on-one interactions throughout the year.

Methods

In an attempt to gather data from more students both inside and beyond my school, I put together a survey via Google Forms. For a variety of structural and contextual reasons, the survey proved most useful in providing opportunities for further interviews. Thus, this paper will focus largely on direct interviews and interactions with students, which you’ll find interspersed throughout the following sections - beginning with one of the School District of Philadelphia’s foundational policies on gender.

Background

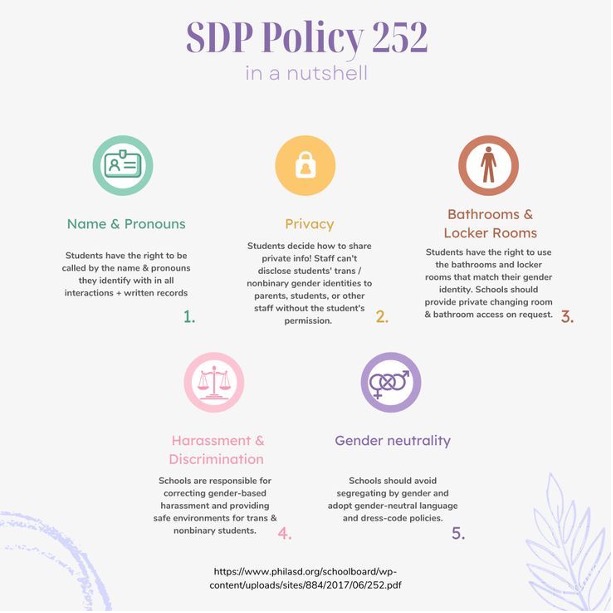

In June of 2016, the School District of Philadelphia (SDP) adopted Policy 252, a multi-layered policy initiative to support students who are transgender or gender non-conforming (or, as I’ve been putting it, trans or nonbinary). Among other provisions, the policy gives students “the right to be addressed by a name and a pronoun that corresponds to the student’s gender identity” in all school interactions and written documents, along with “the right to keep one’s transgender identity private at school.”

To ensure that privacy, the policy states, school staff “should not disclose information that may reveal a student’s transgender identity or gender nonconformity to others, including parents and other school personnel, unless the student has authorized such disclosure.” As we’ll see in the next part of the story, staff interventions can sometimes focus more on ‘resolving the problem’ at the expense of the student’s agency in mediating the divulgence of their nontraditional gender identity – and in violation of Policy 252. You can read the full text of the policy here.

Policy 252 is a remarkably progressive initiative in gender inclusion.

That Philly public schools have managed to convert community support into concrete policy, especially within a system rife with competing demands, is encouraging.

For contrast, we can look to Oklahoma, where I grew up and attended school. While working on this project, I didn't have to go back more than 24 hours in the Twitter feed of Governor Stitt's communications director, Carly Atchison (@CarlyAtch), to find content spotlighting - usually, attacking - school policies that allow trans kids to use the bathroom or play on the sports team provided for their gender. On this occasion, she spotlighted State Secretary of Education Ryan Walters’s letter to the Stillwater School Board, one of the state's major school districts, in early April 2022. He writes,

"Today I am asking you to work with your fellow board members to make it so that your students only use the bathroom of their God-given natural sex...If your board fails to reverse from this present course, I will do everything in my power to protect the children of Stillwater and restore safety and common sense."

In the face of a steadily rising tide of bills targeting trans folks, why mount an inquiry within one of the more progressive school districts? Is scrupulous self-criticism really what we need when, at a larger level, our country's schools are on such radically different pages? Surely, we have better places to put our energy.

These are the questions I'm wrestling with as I write this. Look at it this way, though.

Teachers in districts whose policies don't support trans & nonbinary students have to contend with obstructive administrative and bureaucratic systems as they work to make gender-inclusive spaces.

As this inquiry will show, teachers in districts whose policies do support trans & nonbinary students...also have to contend with administrative and bureaucratic systems as they work to make gender-inclusive spaces.

The key, in both cases, is to know where the "sticking points" for your students are in those systems.

Sticking Point: Roster Names

“[Deadname] is now [Name] and uses [pronouns]”

Since before Ferris Bueller’s Day Off – since time immemorial, in the scheme of American public education – calling roll has been a school procedure as standard as pencil sharpening and hand raising. For teachers, it can be a start-of-year struggle point as we pair names with faces and work on pronunciations and preferred names. For students, the stakes can vary. Mike might bristle at being called Michael, but you might ruin Aiden’s day if you still have “Ada” on the roll.

Socially, it’s an unusual situation. We normally tell someone our name upon a first meeting, rather than having them tell us. Whether or not we get a student’s name right, they’re compelled to respond. It’s an example of the kind of process that critical theorist Louis Althusser would say “transforms the individual into subjects” (1970). Students are saddled with (“interpellated by”, in Althusser’s words) our ideologically shaped notions of them in the moment they have to respond to that roll call. In Aiden’s case, that now involves public recognition of what may be a sensitive private history. Not only does it single out that student at a crucial moment of first impression with peers, but it can also call up memories of suffering experienced while in the closet.

Administrators at my school tried to troubleshoot this by creating a running “Transgender & Non-Conforming Student List” Google Doc, which was linked in the weekly staff newsletter. Other queer educators I spoke with recoiled at the idea of a “tracking” document like this – we certainly hoped we weren’t on any such list – and some found the use of deadnames insensitive at the very least. (The common format for entries was “[Deadname] is now [Name] and uses [pronouns].”) My administrators’ response, though, is by no means malicious, or even particularly ignorant. Rather, it’s a consequence of the rigidity of the larger administrative and bureaucratic systems in which we operate.

As we saw with Othello, roster names can be one sticking point for trans and nonbinary students. Here, we see an example of how small-scale systems that attempt to troubleshoot this resulted in students’ being problematized as administrative issues that needed special tracking. On an administrative level – that is, the level for which teachers are responsible to superiors – teachers’ investment may be less in students’ developing and sometimes fluid identities than it is in “getting it right.”

Systems-level shifts to address trans invisibility are necessary if we want more than patchwork approaches to gender inclusivity - in short, if we want to be proactive rather than clumsily reactive. Here, invisibility is not a piece of theoretical jargon or a metaphor, but a real description of what does and doesn't register through our systems' perceptive apparatus. Genderqueer students don't appear in birds-eye-level district demographics because they don't appear on the most local records. And the longer a group is invisible, the more intimidating and potentially dangerous it is to be the first to poke your head out. Just as infrared light is invisible to the human eye, despite the fact that it can be viewed using special equipment, genderqueer folks are invisible by default unless they enter into clunky and sometimes cagey bureaucratic systems.

Sticking Point: Being Misgendered

Policy 252 gives students the right to be addressed by a name and pronoun corresponding to their gender identity, in both 1) school interactions and 2) written records. The distinction between those two spheres will prove useful for our inquiry here, as written records are generally more the domain of bureaucracy and administration. As we’ll see, though, students’ interactions with staff can also be impacted by administrative and bureaucratic concerns.

If getting a student’s pronouns right seems like a cumbersome new formality – and undoubtedly it does for some teachers – take a cue from something Otis said to me. When a teacher gets his pronouns wrong, Otis wrote on my survey, he tends to “feel sluggish the rest of the day. Being mis-gendered takes a lot out of you and when you have really bad anxiety on top of it all doesn't help you correct them so they know."

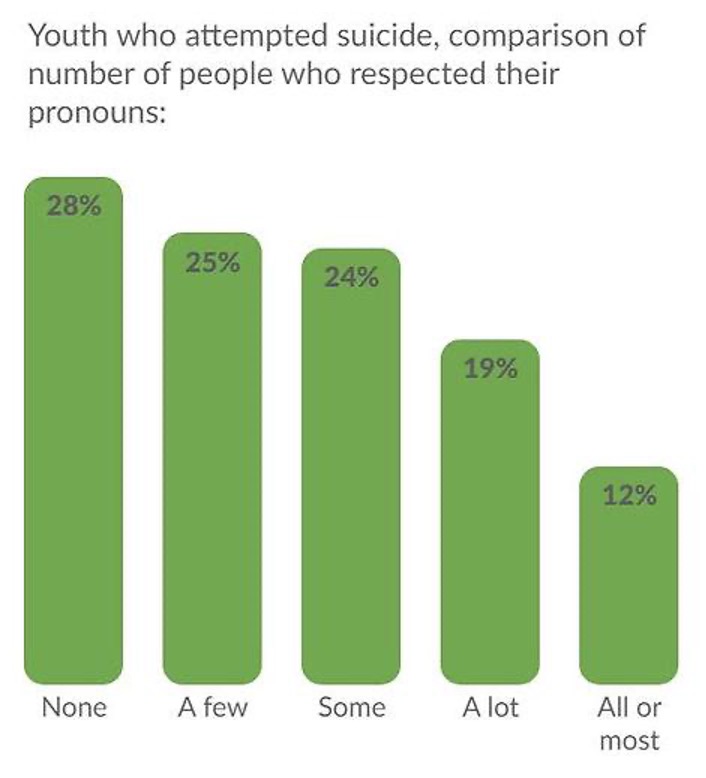

Figure 1

Suicide Attempts and Pronoun Usage

Note. Youths whose pronouns are respected report measurably lower rates of suicidality, according to the Trevor Project's "National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health 2020".

Enforcement of Policy 252’s provisions for name and pronoun use in personal interactions with students and staff is difficult and, consequently, minimal. In interviews, students reported experiencing different degrees of adherence in different spaces. All three students I interviewed - Azure, C., and Otis - reported having teachers who misgendered them. Azure and C., who self-identify as genderfluid or nonbinary, respond to this in part by being selectively "out".

“There are a lot of teachers where I can’t really tell if I’m comfortable enough to come out to them, but there are some teachers and students I feel more comfortable with,” C. said. They don't like correcting other students and teachers about their name and pronouns, though over the course of the year they've begun to identify exclusively with their chosen name and they/them pronouns. "I just kind of stay in my own lane. I don’t like when people look at me.”

"Teachers, they don’t really listen at all," Azure told me. "You can tell them something and they’ll basically discard it the next day." Some teachers had explicitly violated the right to privacy afforded by Policy 252, though Azure himself didn't know about this right until I mentioned it in our interview. "At my old school, I had one teacher who texted my parents about it when I told them.”

For Otis, being deadnamed or misgendered is particularly hard. "Hearing the other name [his deadname], it reminds me of how much I suffered when I was younger. And it’s just like, no, that’s not me. No.”

While interpersonal interactions in schools are not always responsive to policy changes, positive facilitation can be powerful. In our interview, Otis, who self-identified as a transgender female-to-male, described a positive experience transitioning in school when returning after Covid. This was largely due to a positive interpersonal interaction with the school principal, who approached him directly, mentioned she'd heard he was going by Otis now, and asked whether he'd like her to make that transition seamless with the rest of the school. "I was like, yes, please," he remembers.

For Otis, the principal served as a ferryman in an otherwise turbulent crossing. Because she had specialized knowledge and access to the relevant administrative and bureaucratic systems, as well as a leadership role capable of informing interpersonal interactions with staff, Otis's experience of transitioning at school was largely smooth.

Sticking Point: Written Records

Early in the 2021 school year, the district distributed to all staff a Google form designed to process changes to students’ names and gender designations in the various written records systems. The form evolved throughout the 2021-2022 school year to include increasingly explicit information for students about the different records systems and who has access to them.

Students’ concerns here are typically simple: “Who do I want to be out to at school and at home?” In written records systems, though, that basic question of self-divulgence gets complicated. The Student Information System (SIS), for instance, exports to report cards and certain standardized assessments like the STAR tests – information accessed by parents and guardians. Likewise, guardians can be invited to view a student’s progress in Google Classroom, meaning a name change there might also need careful consideration. If a student isn’t out at home, they can just change their “nickname” in SIS, which…should remain between them and their teachers?

As a teacher in the district researching this subject, even I can’t tell you for sure. The complications behind the different administrative systems, and the questions of who has access to what (or might have, should systems procedures change), leave me leery of making a straight recommendation to a student who may be facing high stakes at home. It’s no surprise that some students choose to avoid the automated name and gender change system entirely and just talk to their teachers, even if it means having the wrong information displayed on their pages every day.

Just like that, one of the simplest questions we can ask each other – “What’s your name?” – becomes positively dizzying. And, as Azure expressed to me, “What if I change my mind later?”

- expressed a similar concern with transitioning written records. "If I do decide that maybe this isn’t really right for me, I’d have to end up sticking with it and just having to deal with it afterwards.”

Azure and C. bring up an important point. Some folks’ gender identities are more fluid than others. If our primary concern from an administrative level is setting something in stone, or if the consequences of making any change at all are liable to be lasting, are we really providing space for the kind of identity exploration adolescents need?

All Genders, Report! When Our Systems Put Gender in the Spotlight

For some readers, it may seem like I'm over-elevating the issue of gender, and a minority issue, at that. Why does everything have to be about gender, anyhow? So, let’s ask: when and where do schools make students' gender relevant?

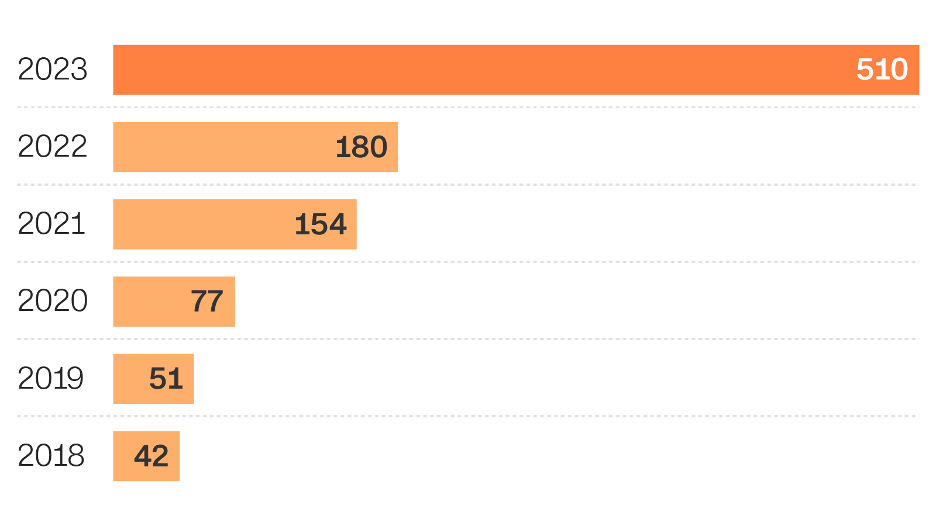

Figure 2

Proposed Legislation Restricting LGBTQ Rights, by Year and State

Figure 3

Note. From “Legislation targeting LGBTQ rights nearly tripled between 2022-2023” (Choi 2024). Via CNN, with data from the ACLU.

Initiatives like North Carolina's now-infamous "bathroom bill" have shown how restrooms and locker rooms in particular can become sites of dispute for questions of gender ideology and rights. Likewise, sports and dress codes have historically been areas where schools show deep investment to the gender binary - and, too often, where authority figures decide where on that binary students belong. Though these flashpoints loom large in American party politics and increasingly attract the legislative efforts of Republican lawmakers, they're a world apart from the realities of public education.

For instance: In March of 2022, a supermajority of Utah lawmakers overrode the governer's veto of a bill banning trans girls from playing on girl's sports teams. Legislators in Arizona and my home state of Oklahoma followed suit.

In a letter explaining his decision to veto the bill, Governor Cox of Utah, a Republican, had pointed out that the entire ban, with all its complex and at time dubious drafting history, would apply to one, single child athlete, while the message would impact trans students already facing severe challenges. In his letter, the Republican governor cites a recent study on "Suicidality Among Transgender Youth" (Austin et al, 2022).

"Here are the numbers that have most impacted my decision: 75,000, 4, 1, 86 and 56.

- 75,000 high school kids participating in high school sports in Utah.

- 4 transgender kids playing high school sports in Utah.

- 1 transgender student playing girls sports.

- 86% of trans youth reporting suicidality.

- 56% of trans youth having attempted suicide

Four kids and only one of them playing girls sports. That’s what all of this is about. Four kids who aren’t dominating or winning trophies or taking scholarships. Four kids who are just trying to find some friends and feel like they are a part of something. Four kids trying to get through each day. Rarely has so much fear and anger been directed at so few. I don’t understand what they are going through or why they feel the way they do. But I want them to live. And all the research shows that even a little acceptance and connection can reduce suicidality significantly. For that reason, as much as any other, I have taken this action in the hope that we can continue to work together and find a better way. If a veto override occurs, I hope we can work to find ways to show these four kids that we love them and they have a place in our state."

Alongside athletics, Republican lawmakers have targeted policies allowing trans girls and women to use women's restrooms, explicitly framing them as exposing (cisgender) girls and women to assault.

The reality? My trans & nonbinary students try to avoid the bathrooms at school.

“I wish there were gender neutral bathrooms here," C. told me. "A lot of the times people in the girl’s bathrooms are like, ‘You’re not supposed to be here, I don’t think.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, I’m not sure where I’m supposed to go. I’m not going in the boy’s bathroom, because I don’t know what they do in there.’”

"If I really have to go, I'll try to use the bathroom in the nurse's office," Otis said.

A report on "Gendered Restrooms and Minority Stress" (Herman, 2013) suggests my students' concerns are widely shared and unfortunately valid. Trans and nonbinary folks face harassment at an alarming rate in public restrooms, with 68% of respondents reporting incidents. More alarmingly, a full 9% of survey respondents reported experiencing physical assault in public restrooms.

Notably, calls to restrict trans folks access to restrooms are not coming from women's rights groups. As trans advocates point out, places that have passed gender-inclusive restroom policies have not seen an increase of sexual assault or rape.

Over 270 organizations focused on combatting sexual assault affirmed made a powerful statement in the 2013 "National Consensus Statement of Anti-Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Organizations in Support of Full and Equal Access for the Transgender Community":

"States across the country have introduced harmful legislation or initiatives that seek to repeal non-discrimination protections or restrict transgender people’s access to gender specific facilities like restrooms. Those who are pushing these proposals have claimed that these proposals are necessary for public safety and to prevent sexual violence against women and children. As rape crisis centers, shelters, and other service providers who work each and every day to meet the needs of all survivors and reduce sexual assault and domestic violence throughout society, we speak from experience and expertise when we state that these claims are false."

I hesitate as I write this. Dredging up research to combat the fundamentally baseless assumption that trans folks are sexual predators feels gross, a regrettable acquiescence to a harmful agenda that should never have had as much screen time as it's garnered over the past few years. Who put my students on trial just for being who they are and needing the same protections as any other kids?

What I missed: Reflections on my own gender inclusion initiatives

Whether it's in-person or online, I don't make my students state or display their pronouns. Having to share my pronouns in a basic introduction always makes me wildly anxious. It basically guarantees I'll spend the next fifteen minutes stressing out internally instead of paying attention to whatever is going on around me.

Some trans and nonbinary folks like having this chance to make sure they're gendered correctly. Others, like myself, would rather be able to choose whether, when, and how to divulge that information. As one friend put it, "Just because a space is safe for you doesn't mean it's safe for everyone."

Mandatory pronoun culture creates an accelerated moment of decision that forces some folks into a crisis of authenticity, on the facilitator’s timeline rather than their own, and often without having a chance to vet the environment. If you didn't want to draw attention to your gender identity in this moment, you now have to decide between your safety & comfort and your sense of authenticity.

Imagine if we started meetings by saying, "Go ahead and share your name and whether you're gay." And you tend to be the only one to volunteer that information. Every. Time.

So, how can we create "nests" for students of diverse gender identities in the classroom? Here are some things I've tried (and am still trying), for better and worse.

To start, I try to reduce the gendered assumptions in my classroom and leave space for students to bring in - or leave out - whatever they want to about their gender. Even for cisgender students, I find it's good to keep a healthy distance from "boys don't" and "girls should." For trans and nonbinary students, reducing the amount of gendered assumptions can keep them from having to be the ones to speak up about why that assumption might not apply to them.

If I don't know a student's gender identity, I'll try to leave that space assumption-free until they express it. That might mean using neutral pronouns (they/them) for them; using their name to avoid pronouns entirely (easier than you would think, in a classroom of 30 students where pronouns tend to birth the question, "Who?" anyway); and avoiding gendered references and groupings ("How's my group of boys over here doing?" "As a girl, you can probably relate to what the character here is saying..."). Instead of making them share their pronouns, though, I'll invite them to share their pronouns if they like to and make a point of providing multiple kinds of spaces for them to practice different levels of self-divulgence in that regard.

On my start-of-semester questionnaire for students, I spend three questions - all optional - asking about the pronouns they'd like me to use for them with their families, in class, and in private. Why? Because those aren't always the same. Some students may not be out at home, or their being out may be a source of contention with their guardians. Others may not be out in school, either, but appreciate the supportive space to be seen by a teacher. Differentiating this allows students to be themselves while also being safe, and it lets them know that you as their teacher care enough to pay mind to the complexities of their lives.

Now, let's talk about what I missed.

Throughout the year, a few shortcomings have become evident to me:

- Making the pronoun selection a single selection answer limits those students who go by multiple pronouns. Multiple selection would be a better survey option.

- By asking for students' pronouns without giving them a chance to describe their gender identity if they'd like to, I fall into the trap of prizing "getting it right" over actually understanding my students. Over the course of that first semester, many students were eager to tell me about their gender identities. Not all students who go by the pronouns assigned to them at birth identify as cisgender, and students who use the same pronouns may carry different identities. Some of my students who identify as genderfluid and use multiple pronouns (he/they, he/she/they...), for instance, like it when people vary the pronouns used for them. If my primary concern is using "the right pronoun" without learning more about them, I'll miss the opportunity to welcome their gender expressions into the classroom.

- Sending this form out only at the start of the semester counts on students having established and static identities, which, as parents and teachers can tell you, is famously not how adolescence works. I ended up counting on my attentiveness and individual relationships with students to provide pathways for verbal updates throughout the year. As I've mentioned, requiring students to come talk to a teacher personally can be a barrier for some.

- Doing a start-of-year survey also asks students to trust me with information about their gender identities before we've developed a rapport. Next year, I'll create an always-available form where students can make me aware of ongoing updates to their pronouns and preferred names.

Here are a few other ways I've tried to create a gender-inclusive space in my classroom:

- Using quality texts from trans and nonbinary authors that yield curriculum-relevant opportunities for analysis beyond tokenizing examinations of their gender identities

- (If you're wondering where to start, Google “trans and nonbinary authors”. I use a lot of Danez Smith, because I love Danez Smith. Find what works for you.)

- Asking trans and nonbinary students if they'd like me to correct other students when they misgender them. Some are relieved to have someone willing to take on that awkward task for them, while others prefer to fly under the radar.

- In general, if you're an ally, you should ask how you can best help!

- Taking little opportunities to diversify your gender choices in example scenarios and sentences

- Showing how language evolves by touching on the grammatical history of the singular they, including the analogy to the singular you. Warning: ELA deep-dives below!

- An article from the APA shows how the singular they and you work similarly in grammar:

- The singular “they” works similarly to the singular “you”—even though “you” may refer to one person or multiple people, in a scholarly paper you should write “you are,” not “you is.”

- An article from the Oxford English Dictionary shows the similarities in the evolution of the singular they and the singular you:

- You functioned as a polite singular for centuries, but in the seventeenth century singular you replaced thou, thee, and thy, except for some dialect use. That change met with some resistance. In 1660, George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, wrote a whole book labeling anyone who used singular you an idiot or a fool. And eighteenth-century grammarians like Robert Lowth and Lindley Murray regularly tested students on thou as singular, you as plural, despite the fact that students used singular you when their teachers weren’t looking, and teachers used singular you when their students weren’t looking.

- An article from the APA shows how the singular they and you work similarly in grammar:

Creating a gender-inclusive classroom is an ongoing effort, and I'll need to keep adapting to my students' needs throughout my career. Some things that come intuitively to me as a nonbinary teacher won't come intuitively to you. Likewise, my being "up to date" on queer gender identities is a limited state of affairs. Our understandings and expressions of gender will continue to change and evolve, and it will be my job to continue creating inclusive spaces for students even when it passes my own personal philosophies or threshold of understanding. How will I respond, for instance, if I have a student who uses "it/its" pronouns - something that feels uncomfortable to me, but may be essential to my student's comfort?

All of that is okay. It's work, but it isn't separate from the larger work of getting to know who our students are and where they come from. To teach our students well, we need to know them. And in my opinion, that's the best part of the job.

What Can You Do?

I have a new rule since I started teaching: If it doesn't have praxis, I don't have time for it.

Educators have hundreds - literal hundreds - of micro decision-making moments with our students every day. Every opportunity we take advantage of or miss is one that we could have done differently. The one thing we can't do is nothing, and so, we do our best.

With that in mind, here's my pitch on what you can do and encourage others to do.

- Do the basics.

- Ask how your students want to be called and give respect when you have their answer.

- Use gendered language intentionally and gender-neutral language whenever possible.

- Don't segregate your classes based on gender.

- Don't let harassment find a place in your class or your school.

- Know the basics about your students' identities. If you don't understand something, Google it.

- Stay privy to your local politics.

- Keep an eye on the bills and policies pertaining to trans rights currently under consideration for your state, city, and school district.

Use this legislation tracker from the ACLU to click on your state and see an easy list of bills currently in the legislature, along with a list of the representatives sponsoring them. One of them might be yours, which means you can make that phone call.

- When you think about diversity, include gender diversity.

- Looking to include books from diverse authors, spotlight change-makers from marginalized communities, or showcase the accomplishments of history's hidden figures? Think intersectionally and consider gender diversity.

The terms we use today - nonbinary, genderfluid, transgender - weren't always in use throughout history. Thinking about gender as a socially constructed category lets us learn from the ways different cultures, eras, and individuals thought about and expressed gender, opening the door to better understandings of how our own ideas of gender have developed and evolved.

- Keep a list of resources.

- Keep basic resources for education, advocacy, and health on hand for students, parents, and fellow educators who might need them. You'll find some of my home-made infographics in Appendix A.

Below are a few other resources. Great news: I found them all by googling, and you can find more stuff the same way.

- A Guide to Being an Ally to Transgender and Nonbinary Youth (from the Trevor Project)

- Guides for Parents from the Human Rights Campaign, including guides to public advocacy, transitioning in schools, and supporting your kids

- Databases of mental health providers who work with trans & nonbinary adolescent (from the Children's Hospital of Pennsylvania)

- City-specific resources like the Mazzoni Center in Philadelphia, which offers youth drop-in clinics; the text of Policy 252 for fellow educators; and the link for name & gender-change requests for your students

- Be mindful of sticking points for students in your environment.

- There's no shortcut for this one. Come up with solutions that make sense for your classroom and your students. Generally, that's going to involve talking to your students to learn how you can help them feel safe at school.

Appendix A

Figure 4. Risk Factor Stats for Trans & Nonbinary Youth

Figure 5. Classroom Counterspells for Gender-inclusive Spaces

Figure 6. School District of Philadelphia Policy 252 in a Nutshell

Figure 7. 8 Basic Sticking Points for Trans & Nonbinary Students

Althusser, Louis. (1971). "Ideology, and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation)". Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Verso Books.

Atchison, Carly. (@CarlyAtch). (2022, April 18). Stitt, a Republican, blasted the school board’s decision as being "wrong" on "every single level." "There are biological differences between male and female and teenage boys should not be given open access to a girls bathroom or locker room." [Link attached]. [Post]. X. https://twitter.com/CarlyAtch/status/1516156958583267333?t=5ohqXHs9hx-fNIRSt6OONA

Austin, A., Craig, S. L., D’Souza, S., & McInroy, L. B. (2022). Suicidality among transgender youth: Elucidating the role of interpersonal risk factors. Journal of interpersonal violence, 37(5-6), NP2696-NP2718.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, New York, 33.

Choi, A. (2024, January 3). Record number of anti-LGBTQ bills were introduced in 2023. CNN. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.cnn.com/politics/anti-lgbtq-plus-state-bill-rights-dg/index.html

Cox, S. J. (2022, March 22). Gov. Cox: Why I'm vetoing HB11. Utah Governor's Office. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://governor.utah.gov/2022/03/24/gov-cox-why-im-vetoing-hb11/

Demissie, Z., Rasberry, C. N., Steiner, R. J., Brener, N., & McManus, T. (2018). Trends in Secondary Schools' Practices to Support Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Students, 2008-2014. American journal of public health, 108(4), 557–564. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304296

Herman, J. L. (2013). Gendered restrooms and minority stress: The public regulation of gender and its impact on transgender people's lives. Journal of Public Management & Social Policy, 19(1), 65.

House Bill 2, 2016, 2016 Second Extented Session. (North Carolina 2016). https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2015E2/Bills/House/PDF/H2v3.pdf

Lavietes, M. (2022, March 30). Oklahoma governor signs transgender sports ban. NBC News. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-politics-and-policy/oklahoma-governor-signs-transgender-sports-ban-rcna22210

Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures in 2023. (2023, December 21). American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights-2023

McBride, R. S. (2021). A literature review of the secondary school experiences of trans youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 18(2), 103-134. DOI: 10.1080/19361653.2020.1727815

National Consensus Statement of Anti-Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Organizations in Support of Full and Equal Access for the Transgender Community — NTF. (2018, April 13). NTF. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.4vawa.org/ntf-action-alerts-and-news/2018/4/12/national-consensus-statement-of-anti-sexual-assault-and-domestic-violence-organizations-in-support-of-full-and-equal-access-for-the-transgender-community

Paechter, C., Toft, A., & Carlile, A. (2021). Non-binary young people and schools: Pedagogical insights from a small-scale interview study. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 29(5), 695-713.

Philadelphia City School District - U.S. News Education. (n.d.). USNews.com. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.usnews.com/education/k12/pennsylvania/districts/philadelphia-city-sd-101796

Steinmetz, K. (2016, May 2). Transgender Bathroom: Advocates Say 'Predator' Is Myth. Time. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.usnews.com/education/k12/pennsylvania/districts/philadelphia-city-sd-101796>

The Trevor Project National Survey. (2020). The Trevor Project. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2020/?section=Introduction

Transgender and Nonconforming Students. School District of Philadelphia Policy No. 252. (2016). https://www.philasd.org/src/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2017/06/252.pdf

Utah bans transgender athletes in girls sports despite governor's veto. (2022, March 25). NPR. Retrieved January 15, 2024, from https://www.npr.org/2022/03/25/1088908741/utah-transgender-athletes-veto-override

Walters, Ryan. (April 8, 2022.) [Letter to the Stillwater, Oklahoma School Board regarding their bathroom policy for transgender students.] Retrieved from https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/stwnewspress.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/3/be/3be8f7f0-b775-11ec-895c-2f9595273fc2/62509242e4388.pdf.pdf

Warrier, V., Greenberg, D. M., Weir, E., Buckingham, C., Smith, P., Lai, M. C., ... & Baron-Cohen, S. (2020). Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nature communications, 11(1), 39-59.