Teaching W.E.B. Du Bois and Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward

This article is a collaboration among three Philadelphia public school teachers who wrote curriculum units based on their new learning and research of W.E.B. Du Bois’ groundbreaking book, The Philadelphia Negro (1899) of the Seventh Ward. Du Bois’ book was the first major race study of an African-American urban community ever published in the United States. Teachers Holloway, Moon, and Yau utilize the past and current history of the Seventh Ward being in Philadelphia to give their students the first hand experience of Du Bois’ scholarly work.

Tyriese James (TJ) Holloway, an 11th and 12th grade teacher from Overbrook High School begins his session with a personal narrative about the complex meanings of “home” and shares his class assignments and examples of student works. Similarly, Jeannette Moon, a 7th and 8th Grade Teacher from Penn Alexander School designs her curriculum unit to focus students with the essential question: “What is home?” with mapping, reading of primary sources as well as fictional works of Du Bois. Lisa Yuk Kuen Yau, a 5th Grade Teacher from Francis Scott Key School finds it crucial to introduce students at a young age to the race issue by having them create accordion books, data portraits, and community spaces inspired by Du Bois’ scholar works.

Key Words: W.E.B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro, Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward

Introduction

“Education must not simply teach work - it must teach Life.”

W.E.B. Du Bois, The Talented Tenth, 1903

Ten teachers from the School District of Philadelphia (SDP) participated in a seminar—“W.E.B. Du Bois and Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward”—with the end goal of creating a unit tailor-made for each teachers’ school community. Over the course of five months, Amy Hillier, an Associate Professor in the School of Social Policy & Practice at the University of Pennsylvania, facilitated discussions of reading and critical analysis of Du Bois’ The Philadelphia Negro (1899). While the complexity Du Bois’ lifework resists easy classification, one could argue that his core effort was a social aim for equality and full liberation for African Americans in all areas, including education. SDP teachers wrote distinct curricula to foster social and historic connections of Du Bois’ work for students from elementary to high school ages. The seminar was a teacher professional development program of the Teachers Institute of Philadelphia (TIP), free of charge to public school teachers in Philadelphia. Upon completion, teachers receive a stipend and Act 48 professional development credits.

This article details three of the ten teachers’ units on W.E.B Du Bois, as well as their challenges and progress while teaching their units.

Tyriese James (TJ) Holloway’s Narrative and TIP Unit

Home is a complicated concept for many people. In my life, I have called many places home. When I was a child, I lived in between two adults, my mother and my grandmother. My mother lived in the Morgan Village neighborhood in Camden. My grandmother lived in East Camden. My mother had suffered a stroke and needed help raising two boys until she reconciled that in her old age she was unable to raise us. My brother and I moved from Camden, New Jersey and lived the rest of our childhood in Williamstown, New Jersey. Living in Williamstown, it was a major culture shock compared to living in a city. Our adoptive mother had owned more than thirteen acres of land, and when we had first arrived, we were welcomed by mounds of clay, one swiveling road, and a wide expanse of land marked by a developer named “Ryan Homes”.

We lived behind a springing development called Glen Eyre and we kept an at-arms-length relationship with our neighbors. Oftentimes our surrounding neighbors would become curious, drive their cars down the swiveling road to explore the hosts of trees, honeysuckles, and groves on our property. My mother instructed us to not allow any outsiders on our property, and we were told to send them back their way. We went to school with our neighbors’ children, and we became associates, not friends. We walked about ten minutes from our home, to the sprawling road, to our bus stop. Our “associates” would laugh and joke that we lived in a cardboard box in the field. My mother would call our ranch-style home, “the little house on the prairie”.

I remember my first summer at my new foster home being defined by four different incidents. First, it was my first summer that I did not spend with my little brother, who was at a different foster home at the time. Second, it was my first birthday that I did not spend in Camden, and at ten years old, I learned how to ride a bike. My foster brothers taught me how to ride through a bending slope that sat on the right side of our house– much more patiently than I expected familiar strangers to treat me. Riding a bike is much harder than walking, that is, until my brothers held my shoulders even, my legs wobbling to find center, and I met my fate staring at my front tire. I dusted myself and tried again. Our sticky cups of Cola drew an audience of flies on the front porch, and the sweat of our Solo cups twinned with the dew on our chocolate faces. Biking, not hugs, was something of a foster kid’s inauguration in Mrs. Holloway’s home. Once I graduated, it was the first time that I rode my bike on asphalt, on our sprawling road, and it was the first of many where my changing cast of brothers and myself would vent, decompress, and reflect on our lives while riding on that road. Lastly, it was the first-time I directly interacted with white people outside of school. In Camden, I was raised by a Black family and went to a Black school. In Williamstown, I was raised by a Black family and went to a predominantly white elementary school. My fellow students tolerated me when I was in school, but learning to interact with the entitlement of white adults was a different story. Fortunately, I was with four other boys, some older, for mutual support.

Unfortunately, I came to understand that my mother sold off her inherited acres to Ryan Homes, and that was part of the reason why it felt that my world was becoming smaller. As we grew in shoe size, the land we took for granted became more limited. When we got to middle school, our bus stop changed. The shortcuts that we used to take to our bus stop (only a three-minute walk) returned to being an arduous journey trekking through a circuitous route designed by freshly paved asphalt roads. The dimensions of this inconvenience cannot be understated. As a young teenager, I didn’t care much about my appearance, however, my younger brother certainly did. When it snowed or rained, my brother used to carry two pairs of sneakers. One was his walking sneakers, and the other pair was his school sneakers. Before the change, we would walk to the bus stop and catch the bus, and his sneakers would be relatively dry. By taking the scenic route, both of his sneakers would become sopping wet, leaving all of us at the mercy of his stinking feet. The wide-open field that sat outside of the boundary of our land (which we called “The Trench”), that we used to play football with our neighborhood associates became backyards for townhomes. The mound of clay that invited me when I first arrived to Woods Road, which flourished with weeds, flowers, and brush in the spring, became razed to build a new home. As young children, we understood that we couldn’t have our cake and eat it too. That was not the problem. The problem was that we felt partially responsible for the brand new houses that our overwhelmingly white, snobby neighbors had acquired while we went back to a place we weren’t happy to call home.

The scent of Don Pepino canned tomatoes that welcomed the new school year in Williamstown had frozen over by February; we never heard it, but it was the ghostly warmth of a bullet in Florida that commanded our attention to a family meeting in the front of our kitchen island. My mother spoke plainly. Trayvon Martin, a young Black child was killed near a gated community. We are no longer boys. We are not cute, nor adorable, nor safe. We are becoming men. Do not wear hoodies. Do not ride idle around Ryan Homes property. Be back home before sundown. I felt the spit draw into the back of my mouth. We grabbed our plates and went to the back table, and in retrospect, it feels like that was the last time we talked together as a family.

***

I wrote this unit because I want my students to dig deep to ask the hard, existential questions about home. The leading philosophical question being: can a place be considered home if you cannot determine its future? Home can be easily substituted for setting if one does not become fundamentally aware of their surroundings. I’ve lived in many different places after Woods Road. I moved to Glassboro, New Jersey to attend Rowan University. After four years, I moved to China and visited many different countries in Asia. After my goddaughter was born in Philadelphia, I decided to teach here.

General advice for newcomers moving into Philadelphia is to “keep your head on a swivel,” but for far too long, people (my students included) don’t stop to look up and see the power in their surroundings. I moved to Philadelphia some five years ago, and I’m still astounded by the subtle details the eye can catch that can change the context of the whole environment. For as long as I have lived in Philadelphia, I have stayed in one dwelling in North Philadelphia. Almost every day I would walk by a gated fence without any curiosity, until something caught my eye. The unremarkable detail – light refracting off the shoulder of what I thought was a wall – came to my attention late one night when I recognized that behind the gated fence was a U-Haul garage with a loading dock. There is a terrible irony that there is the looming presence of a corporation in the neighborhood, but it is not connected to a supermarket. Whenever I talk about my neighborhood block with my students, I often discuss how I live in a food desert, notwithstanding the fact that I had to live in a food desert for me to understand what a food desert actually is. The divide between knowing and understanding is an age-old dynamic in educational theory. Living in a food desert, it forced me to question the role of small businesses in my community and how these small businesses feel like spackle on drywall– the mark of unfinished nature of the interior of my community. While my unit of curriculum does have its own convincing objectives, long story short, I want my students to connect to the “emotional” and “spatial” contents of home in order to understand, value, and appreciate their home and communities, that is, to love their community in aspirations to change it before they reconcile themselves to powerlessness.

Objective(s) of Unit:

- Students will evaluate their “place and space” in Philadelphia through personal narrative and artistic expression

- Students will examine the historical legacy of WEB DuBois, the Seventh Ward and Black Heterogeneity in Philadelphia

- Students will investigate the source of crime in the city IOT create solutions to gun violence by means of a research-based choice board

Given the population that I educate and serve, an overwhelmingly Black and low-income student population, I do not want to imply that my students take home for granted. My students are already well aware of the problems that they are facing, and I think it is critical for my students to apply a critical lens to the information that they “know.”

Let me be clear, this unit did not go exactly as planned. This school year Overbrook High School has implemented a rotating block schedule for the first period followed by 54 minute periods afterwards. I planned to teach this unit during the first marking period, but I prioritized my first marking period class foci around essential skills such as MLA format, elements of fiction, and annotation strategies. Although I was not able to teach the unit in the scheduled slot, the new timing helped me introduce the topic of engaged anthropology in an organic way through connecting the social elements present in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, and W.E.B DuBois’ The Philadelphia Negro. In Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, I communicated that the reader saw the financial precarity that Willie Loman had to survive, and how much his identity as a Salesman defined his choices and his opinions. Alternatively, we saw how Biff’s multiple jobs defined his incompetence and his transient identity in American capitalism. The thematic throughline to The Philadelphia Negro was how DuBois discussed the multiple jobs and occupations that Black Philadelphians not only defined but limited their political status. In Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, the protagonist Lauren Olamina lives in a “closed community” in the midst of an ecological and political collapse and that class divisions became clear based on the resources and jobs that Lauren’s neighbors had.

The thematic thoroughline to The Philadelphia Negro was how DuBois highlights the segregation between race and social class in the Seventh Ward but also affected the perceptions that DuBois had of these communities as reflected in his legendary map based off his schedules. With this understanding, students were visually able to see how Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London inspired DuBois’ The Philadelphia Negro through my comparison of their maps and respective legends.

In the beginning of the first marking period, we did an anticipation guide centering themes present in Parable of the Sower. By the time I started this unit, we revisited a lot of the thematic statements in the anticipation guide to determine if there was a change of heart from the first time they interacted with these statements. Surprisingly, there wasn’t much of a change of heart from their initial engagement. When introducing the City in the Box assignment, I encouraged students to engage with this assignment as anthropologists. As an addendum to my original curriculum unit, students were assigned “Spatializing Culture” by Setha Low. In this article, Low names engaged anthropology as a touchstone to her methodological framework. By her definition, engaged anthropology are activities “that grow out of a commitment to the participants and communities anthropologists work with and a values-based stance that anthropological research respects the dignity and rights of all people and have a beneficent effect on the promotion of social justice” (Low, 2017. p. 34). Engaged anthropology is in the spirit of the work of applied sociology that was led by DuBois and the Christian Settlement Movement.

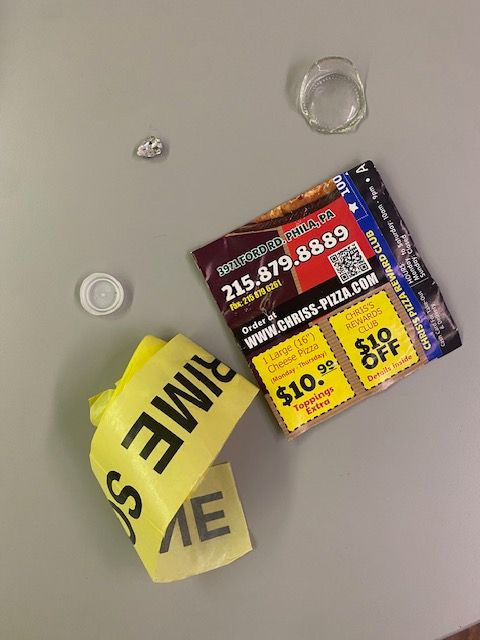

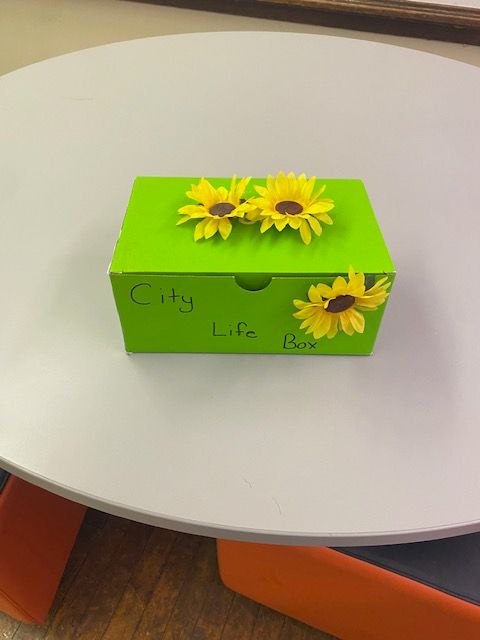

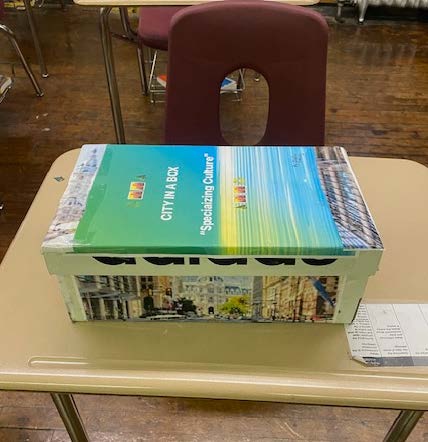

When giving the directions for the City Life Boy project, I encouraged students to get creative with the “found objects” that reminded them of their home and their neighborhood, and said that it is important that these items have a narrative. Students have brought in business cards, combs, juice bottles, honeybun wrappers, and family photos they took at their new homes, and also felt challenged to think about their home spatially and locally.

Above photos are examples of “found objects” that were brought in by students for Holloway’s “City Life Boy” project. Below photos are student work from the “City in the Box” assignment.

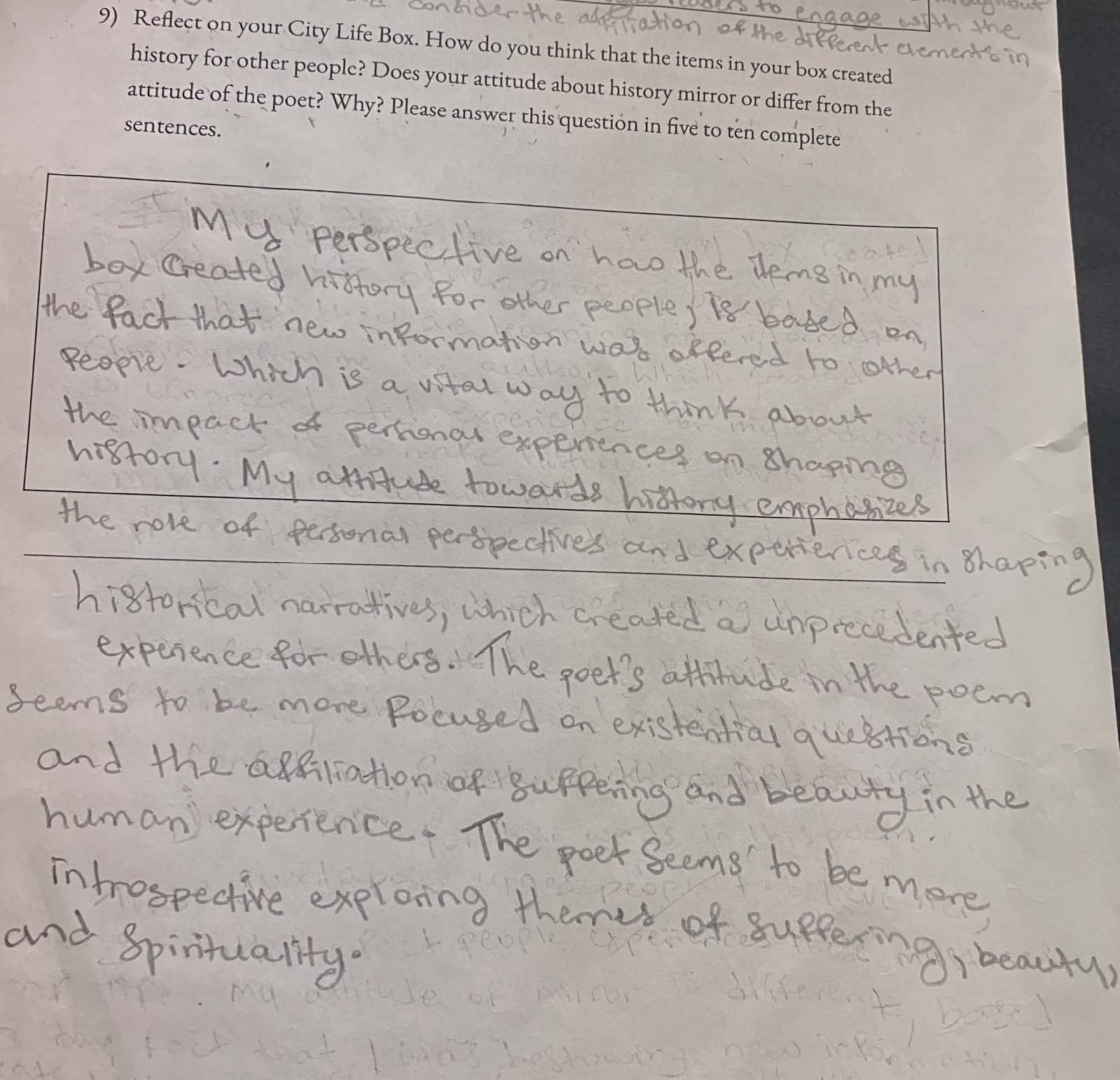

After the City Life in a Box assignment, students were challenged to annotate, analyze and reflect upon the poem “History as a Process” by Amiri Baraka. After they read the poem, they were tasked to answer the following questions as a prompt: “Reflect on your City Life Box. How do you think that the items in your box created history for other people? Does your attitude about history mirror or differ from the attitude of the poet? Why?”

Above photo is a student reflection about the City Life Box assignment. It reads: “My perspective on how the items created history for other people is based on the fact that new information was offered to other people. Which is a vital way to think about the impact of personal experiences on shaping history. My attitude towards history emphasizes the role of personal perspective and experiences in historical narratives, which created a unprecedented experience for others. The poet’s attitude in the poem seems to be more focused on existential questions and the affiliation of suffering and beauty in the human experience. The poet seems to be more introspective exploring themes of suffering, beauty, and spirituality.”

I hope that by fostering a mind that is attentive to locality, students become more aware of the influence they have to make in their neighborhoods better, while at the same time addressing their own needs and the needs of others. Additionally, I hope that through this awareness building, they will be more empowered to fight against economic forces that do not have their neighborhood’s best interest in mind.

Jeanette Moon’s Narrative and TIP Unit

Grounded in W.E.B. Du Bois’ mapping and analyses of The Seventh Ward in The Philadelphia Negro, this unit explores the essential question of “What is home?” In this unit, students will define home for themselves through text and map analyses, culminating in an option of three end of module assessments. For this assessment, students choose between defining home via a map, argumentative essay, or narrative, and include an analysis of their choice. Students explore and analyze primary and secondary documents throughout the unit, starting with Du Bois’ Seventh Ward maps. As they move through the unit, students practice form, tone, and genre analysis that they will apply to their peers’ and their own writing.

Introduction and Context

I teach seventh and eighth grade Literacy at Penn Alexander School (PAS). As all communities are, PAS is a unique one. It is located at the intersection of 43rd and Spruce, known to some as University City and others as West Philadelphia. The school both produces and is the product of the gentrification of West Philadelphia. PAS is purposefully shielded from the budget constraints of the School District of Philadelphia with funding from the University of Pennsylvania and an active Home School Association, entities that are determined to create, through this one community school, proof that public education works.

I hope to complement this W.E.B. Du Bois based curriculum with a Raisin in the Sun unit exploring the essential question “How do one’s race, class, and/or gender influence an individual’s goals or aspirations?” As Lorraine Hansberry was taught and influenced by Du Bois, students, too, will be able to track ideas and concepts across time and genre.

In March of 2024, I started teaching this unit. We started with background information of Du Bois and The Philadelphia Negro. Students read through excerpts focusing on different charts. They summarized the information from Du Bois’ studies and distinguished between the information Du Bois presents in The Philadelphia Negro and his analyses or interpretations of the information. I have not yet finished this unit but have included some examples of student work below.

Essential Question: What is home?

This Du Bois unit will be guided by the essential question, “What is home?” With this question, students will establish their own definition of home. In doing so, we will consider individual interpretations and societal constraints that define the idea and reality of home.

The abstract question will be anchored by Du Bois’ writing and surveying in both The Philadelphia Negro and other texts (2023). Through analyses of Du Bois’ work and experiences, students will be both exposed to and critical of Du Bois’ ideas of home. A historical figure whose relevance and influence spreads across academic disciplines, Du Bois will provide multiple access points for students to consider home (Hunter; Jones-Everly and Dean, 2018).

Throughout the unit, students will describe home for themselves, gain context for how society defines home, and explore the effects of home. Each section of the unit will culminate in an informational paragraph.

At the end of the unit, students will discuss their ideas from each section in a seminar. After the seminar, students will collaborate or work individually to create a definition of home through an annotated map with explanatory essay, an argumentative essay or a personal narrative with integrated citations. In addition, students will include a caption for their end of module gallery walk that explains the choice of medium they made–why I chose to present my story with a map, essay, narrative etc.

Focusing Question: How is home described?

Du Bois used surveys, interviews, and mapping as a concrete metric to legitimize his research. Methodical and thorough, each of Du Bois’ assertions in The Philadelphia Negro is supported by charts and statistics. However, Du Bois explains, “We remained unrecognized in learned societies and academic groups. We rated merely as Negroes studying Negroes” (Farland, 2006, 1037). Du Bois navigated the paradoxical nature of sidling up to the academic class of people who had hired him – but only for a little while–with maps.

Students explore this paradox by first analyzing the effect of Du Bois’ choices in survey question, category, color etc. While seemingly quantitative in nature, the map categories have both a subjective and objective effect. Students will later apply the analytical skills they used with Du Bois’ maps to create their own map categories and surveys. In doing so, they will begin to gain a foundation for the complexities of defining home.

When students embarked on asking their own mini research questions and implementing surveys, they started to gain understanding of the complexities of the kind of sociological research Du Bois participated in and the challenge of categorizing groups of people in any way. Below are some excerpts from both the students' previews of their research questions as well as their reflections of writing sociological research questions and implementing surveys.

Living close to friends, going to a small school, and being able to do things independently throughout the city has impacted how comfortable I am with people. That causes me to wonder, are other kids in my community more introverted or extroverted and does living in a city encourage that? To study this question, I will survey students throughout my school in order to get a better understanding of their perspectives. Many of my classmates live scattered around the area and have all grown up experiencing a similar type of lifestyle. In cities there are many factors that can influence people to be more extroverted or introverted. Some elements are that people live close, there are smaller schools, there are local places known in the community, more crowds of people, and navigational independence and transportation.”

“The survey process consisted of me asking classmates and friends through text and in person about my survey questions. It's also important to note the potential biases in the survey, like the selection of participants. Also, since only six people participated in this survey, that may limit the findings that could be found in a bigger population. Despite this, I was still able to find that football was perceived as a somewhat dangerous sport among all participants.”

Focusing Question: How does society define home?

Individual Perception: As Du Bois did in his analyses, students will explore the idea of how society and societal factors impact home. Originally printed in The Atlantic and later in The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois describes the idea of “double consciousness.” He defines this as the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity” (Strivings, Du Bois, 1897, p. 194).

As he was surveying people and the environment of the Seventh Ward, Du Bois was simultaneously observing and analyzing the ways in which his race affected others’ perceptions of himself. Du Bois’ analyzes at the end of The Philadelphia Negro describe the effects of perception on the lives of the residents of the Seventh Ward in a section of Chapter 16 entitled “Color Prejudice”: “The difficulties encountered by the Negro on account of sweeping conclusions made about him are manifold…” (Du Bois, 1899, p.339). Du Bois then includes the results of his surveys, with various examples of Black Philadelphians’ employment being hindered by these “sweeping conclusions.”

Having been hired in part because of his shared Blackness with the subjects of his sociological study, Du Bois was intimately familiar with parts of the experiences of the residents of the Seventh Ward. He deftly describes and analyzes aspects of prejudice against Black people. However, as he categorized a section of these same residents as “Vicious and Criminal,” he distinguished himself from this community and “…the community did not fancy itself as an ‘other’ in need of a great intellectual savior; indeed, there was an obvious tension between Du Bois and the city’s Negro elite” (Zuberi, 2004, 149). This disconnect is fictionalized in Wayward Lives as Du Bois’ dress and interloping nature is emphasized: “[Du Bois] was desperate to believe that the refinement of style might make plain what escaped the gaze of the white world–every Negro was not the same” (Hartman, 2020, 84-85). By describing and researching “color prejudice,” Du Bois had the dual effect of validating his own experience while distinguishing himself from certain residents of the Seventh Ward and thus highlighting the limits of his expertise and understanding.

Each of these texts provides a distinct lens into Du Bois’ ideas about and relationship to racial prejudice. Throughout “Strivings of the Negro People” and The Philadelphia Negro, Du Bois philosophizes and proves the tangible effects of prejudice held against Black people. Wayward Lives provides a narrative version of the complexities that Du Bois embodies as the observer of racial prejudice and the disconnect between his sociological subject matters and himself. Students will explore the relationships between these three texts, both in style arguments about how outward perceptions may affect how home is defined. As the residents of the Seventh Ward are not a monolith, neither is Du Bois. Rather than codifying Du Bois’ own “double consciousness” as a singular descriptor, students will have the opportunity to analyze the nuances of all three texts.

Focusing Question: How will we tell the story of home?

Du Bois was not limited to surveys and sociological studies. At this point in the unit, students will have read philosophical essays of Du Bois, in addition to the more quantitative sociological study of The Philadelphia Negro. They will also have read a fictionalized account of Du Bois in Wayward Lives. Later in his career, Du Bois himself would also write fiction. When he “Tout[ed] the ‘literary possibilities’ of the ‘severely scientific’ Lowndes County study, DuBois foretold his occupational shift from science into literature, and his embrace of the ‘efficient means of publicity’ available in the literary realm” (Farland, 2006, 1019). Students will mimic Du Bois’ expertise in different genres. They will choose which genre is most effective and true to their own definitions of home based on the strengths and limitations of the texts they have analyzed.

After reading excerpts from both The Philadelpha Negro and Wayward Lives, students responded to the question: Which medium is most accurate in telling the story of the Seventh Ward? Why? Below are three examples of student responses:

Student A: “The medium that is the most accurate in telling the story of the Seventh Ward is "An Atlas of the Wayward" by Saidiya Hartman. Unlike The Philadelphia Negro by W.E.B Du Bois, "An Atlas of the Wayward" uses Du Bois' research and builds on it even further from a narrative perspective. It goes into detail about black families in the ward and says, "The drama hiding behind the statistics and sewed gender rations went something like this: Two young people not in a financial position to wed or support a family entered a thoughtless marriage. The husband, being unable to support the wide and now a child on his wages, needed her to work too..." (page 91). The Philadelphia Negro paints this picture as extremely poor families, who do little to nothing to solve their issue. Saidiya Hartman on the other hand, shows the true reason for this, and how the lives of black families are from an emotional perspective, which is more appealing. To conclude, the medium that best tells the story of the Seventh Ward is Hartman's book, "An Atlas of the Wayward" because it extends on Du Bois' research, and shows it from a different, more emotionally appealing perspective.”

Student B: “When it comes to telling a story, Wayward Lives is most accurate in telling the story of the seventh ward. For one, Wayward Lives gives fictional, yet accurate accounts of peoples lives. It states, "The summer weather, like the Seventh Ward, was intemperate and volatile." By using descriptive storytelling, this medium better defines the seventh ward. For the average reader, stats and graphs don't always have meaning. Instead, descriptive stories outline the true positives or negatives in an environment."

Student C: “I think that Du bois/The Philadelphia Negro because in the other passage, "An Atlas of the Wayward," it didn't give really good information about the Seventh Ward. I think this is because I feel like it wasn't really focused on telling the story of the entire Seventh Ward and finding out why the people in it were so bad; it just told stories about things in the Seventh Ward that were relevant but didn't tell us how. For example "As late as 1944 he writes of a "far-seeing leadership" and of the elites "those individuals and classes among Negros whose social progress is at once the proof and measure of the capabilities of the race." See "My Evolving Program for Negro Freedom.". But with The Philadelphia Negro it gives us accurate information on where the bad places were and why they were bad and how they ended up in these situations of poverty.”

Lisa Yuk Kuen Yau’s Narrative and TIP Unit

In the midst of writing my curriculum unit in May 2023, I showed my 5th grade students a photo of Du Bois with his top hat and asked, “Who is this?” None of them knew who he was. One student with great certainty immediately shouted out, “Martin Luther King!” I was not completely surprised, but felt utterly disheartened. This encounter confirmed for me the importance of introducing students at an early age to who Du Bois is as well as who he is NOT. Furthermore, I refuse to fall into the trap of perpetuating the “single hero, single story” myth that limits the many accounts of Black excellency, reduces the complexity of the civil rights movement to just MLK, and minimizes the ongoing fights for social justice and equality as part of the past.

I have taught in the School District of Philadelphia for over 23 years, and I’ve been told again and again by skeptics that W.E.B. Du Bois’ ideas of “double consciousness” and his race theory from his groundbreaking book The Soul of Black Folks (1903) are too complicated for young readers like my 5th grade students. This assumption made me more determined to introduce Du Bois’ works and other complex ideas in my classroom. Suppression of progressive ideas, often under the guise of making the curriculum “age appropriate,” has historically contributed to institutional as well as individual oppression of the non-dominant groups.

Many of Du Bois’ writings, such as those in his book The Philadelphia Negro (1899), remain under-shared and under-valued. During the height of the media coverage of George Floyd’s tragic death and the indefinite school shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers across the nation were forced to teach remotely. The day after the January 6 attack (2023) on the U.S. Capital by Trump supporters, I remembered showing an animated video titled “How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?” through Zoom to my then-4th grade students. The video was based on the article “Strivings of the Negro People” that Du Bois wrote for The Atlantic magazine in 1897. After the video viewing, my class had an honest and heartfelt discussion that validated many fears of my students who were Black, Brown, immigrants, and children of refugees. In particular, one Black male student explained why he didn’t want to go outside his house: “There are people who don’t know me… who hate me because I am Black.”

This response shook me to my core and taught me that the urgency in spreading the words of Du Bois requires immediate action. Instead of hushing students about their fears, teaching them to tolerate hatred, and stay away from difficult conversations, Du Bois advocated teaching self-reliance with the goal that “the object of education is manhood and womanhood, clear reason, individual talent, and genius and the spirit of service and sacrifice, and not simply in a frantic effort to avoid change in the present institution” (Darkwater, 1930, p. 8). In his Niagara Movement Speech (1905), Du Bois listed 5 demands. The fifth demand addressed the danger of miseducating our children with the warning that “[e]ither the United States will destroy ignorance or ignorance will destroy the United States” (Du Bois, 1905).

My unit entitled W.E.B Du Bois, and the Making of Accordion Books, Data Portraits, and People Places aims to challenge middle school students with three focused areas of inquiries:

- Who is W.E.B. Du Bois, and why does his book The Philadelphia Negro matter then, now and for the future generations?

- How can Du Bois’ groundbreaking exhibit of data visualization, at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, improve student understanding of self-identity and public health concerns around their community? Du Bois was one of the first to point out the health disparities between White and Black people due to systematic racism with surveys and data.

- How can students use art and creative place-making to maximize the quality of “people places” in a neighborhood? With the term “people places,” I’m referring to meaningful spaces created by people’s individual behaviors as well as communal actions. For example, a city street can be a safe space for kids due to neighborhood watch, and can also easily turn into a hangout for man-child drug dealers and addicts due to building neglect and abandonment.

Throughout my unit, students will engage in the making of accordion books about Du Bois and the Old 7th Ward of Philadelphia, analyzing data portraits of themselves, and designing art proposals of people spaces to address a public health issue. The unit incorporates the teaching standards from 5th grade English Language Art Common Cores in Writing and Speaking (W.5.10 and SL.5.1.C), from K to 12th grade National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) on Data Analysis, and from 5th grade Pennsylvania Social Studies on Geography and the Human Characteristics of Places and Regions (PA.7.1.6 and PA.7.3.6).

In October 2023, I introduced my TIP unit on Du Bois to my 5th grade students. The first task was for students to listen to an audio recording of Du Bois and simultaneously read along with the transcription or closed caption. Most people would read about Du Bois and analyze his writing, but it is not often that we hear the voice of Du Bois or see him making his speech. In contrast, most elementary school students have seen at least one photo of Dr. King and heard his “I Have a Dream” speech.

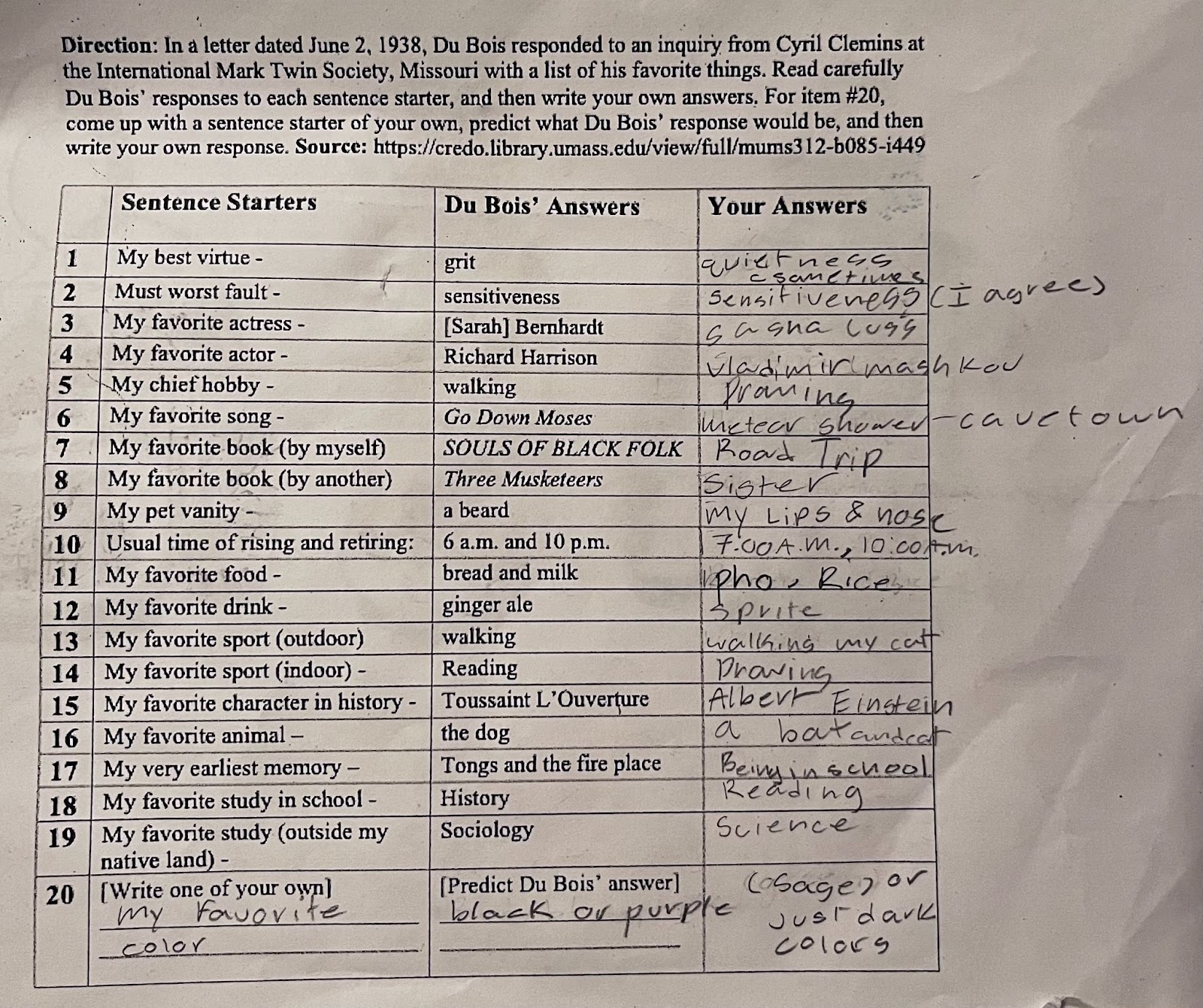

Another introductory task was a compare & contrast activity of favorites. I’ve created a three-column graphic organizer to help students to see Du Bois as a real person with similar or different favorites. On the first column is a list of sentence starters like “My best virtue -”, the 2nd column is a list of Du Bois’ answers, and the 3rd column is left blank for students to write their answers. The list of Du Bois’ favorite things include: “my pet vanity - a beard, my favorite food - bread and milk, my sport (outdoor) - walking, my favorite sport (indoor) - reading, my favorite animal - the dog” The list shows Du Bois as someone who was humorous as well as serious, relatable as well as complex.

Above is a student’s sample answers of their favorite things next to Du Bois’ favorites.

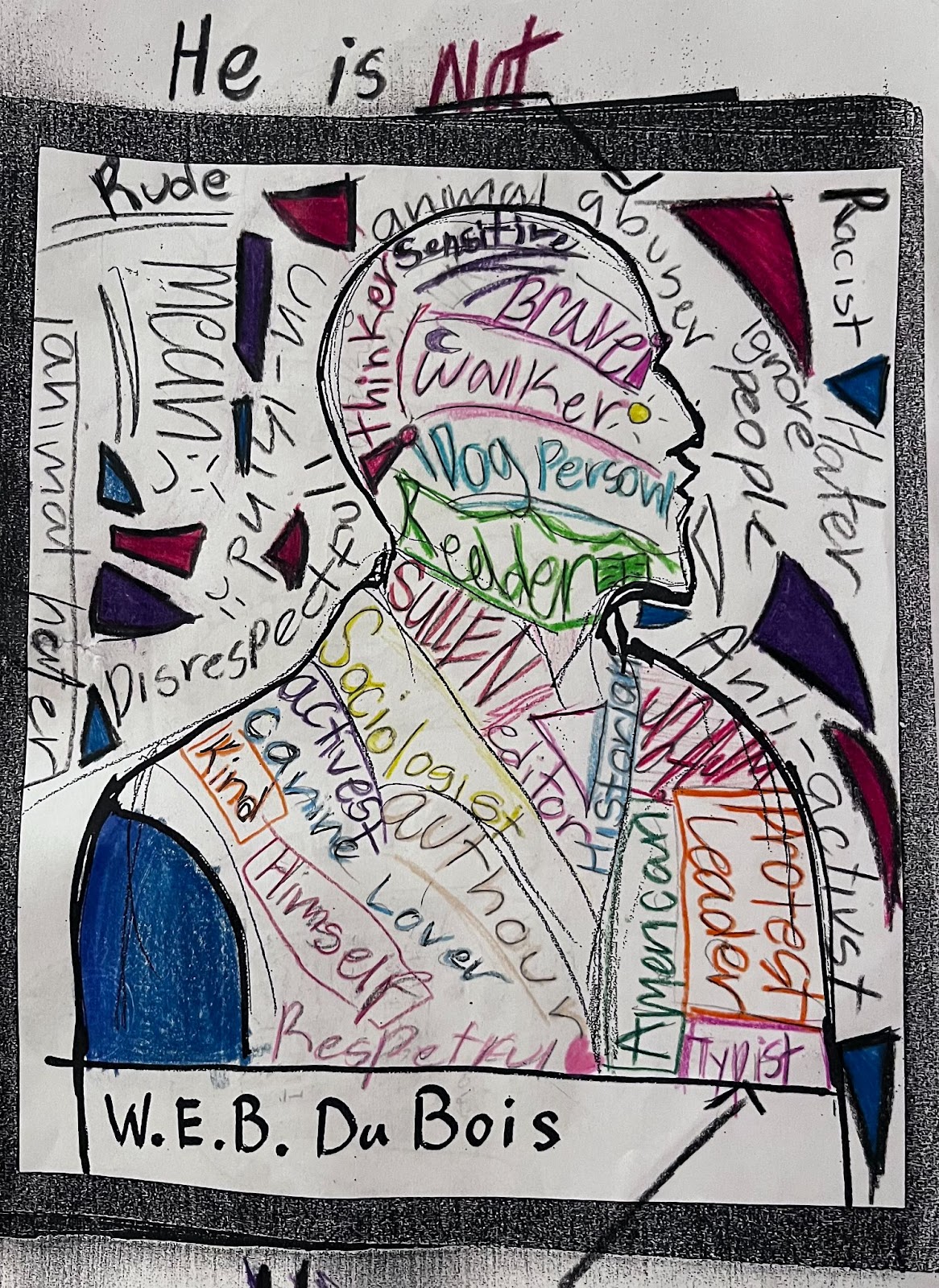

Two other activities focused on research as well as design. One activity asks students to make an accordion book cover using the profile of Du Bois, and my students enjoyed working collaboratively researching words and phrases to describe who Du Bois is as well as who he is not online. Another activity asks to design a hoodie for a “contemporary Du Bois” and my students were most excited about this. One student designed a whole outfit including gloves, pants and sneakers.

Top: Student work on a Du Bois’ book cover.

Bottom: Student design of a hoodie for contemporary Du Bois.

Even though I was not able to teach the entire unit, I believe what I did do with my students was as rewarding to me as it was for them. When I showed the same photo of W.E.B. Du Bois to this group of students, one of them suggested that they should make top hats and wear them during their Black History Month school-wide presentation of Du Bois and point out a historical marker of Du Bois located at the intersection of 6th and Rodman Street in South Philadelphia, a short distance of about 20 city blocks from our school.

Collaborative Conclusion and Reflection

What impact do these units about Du Bois have on teachers and students?

The notable methodologist, Carol Weiss, popularized the term “Theory of Change” (1995) to explain the connections between programs and outcomes from mini-steps to long term impact. The concept is a challenge to designers of community-based initiatives to be specific about their theories of change in order to strengthen their claim for the desired outcomes. In education, the theories of changes aim for educational reform and improvement. In reality, teachers are often not included in the theories of change, therefore, their voices are often nonexistent or minimized in educational policies. Teachers Institute of Philadelphia (TIP) is an organization that promotes and supports teachers as critical researchers, front-runners in defining quality education for our students, and must be included in the theory of change if we want positive results.

Today, standardized testing like the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) rates countries and the quality of their education on a list. But we know that quality is not always quantifiable. The three teachers in this article: Holloway, Moon, and Yau created their Du Bois’ units not only for themselves and their students, but also for other educators as well as policymakers. These curricular units were written based on high-quality content knowledge with the support of university professors who are experts in their fields.

The jury is still out whether supporting teachers as researchers and professional curriculum writers will have a long-term positive impact on education, but we all can agree that the traditional road of using publishers to write our curricula has failed our teachers and students again and again. It’s time to trust and support teachers as professional leaders and authors of education… starting with one teacher and one curriculum unit written by that teacher.

Battle-Baptiste, W., & Rusert, B. (Eds.). (2018). WEB Du Bois's data portraits: Visualizing black America. Chronicle Books.

Boddie, S., & Hillier, A. (2022). The Making and Re-making of The Philadelphia Negro. DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly, 16(2).

Booth, C. (1902). Life and Labour of the People in London (Vol. 1). Macmillan and Company, limited.

Butler, O. E. (2023). Parable of the Sower. Grand Central Publishing.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2022). Darkwater. Simon and Schuster.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1897). Strivings of the Negro People.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2008). The Souls of Black Folk (B. H. Edwards, Ed.). Oxford University

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2007). The Philadelphia Negro. Cosimo, Inc..

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The Talented Tenth (pp. 102-104). New York, NY: James Pott and Company.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2013). W. E. B. Du Bois: Selections from His Writings. Courier Corporation.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1970). W. E. B. du Bois Speaks: Speeches and Addresses.

Du Bois, W. E. B., Francis, J., & Hall, S. G. (2019). Black Lives 1900: W.E.B. Du Bois at the Paris Exposition.

Farland, M. (2006). WEB Du Bois, Anthropometric Science, and the Limits of Racial Uplift. American Quarterly, 58(4), 1017-1044.

Foreman, T. (2018, March 8). W.E.B. Du Bois’ “Strivings of the Negro People,” Animated - The Atlantic. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/video/index/554972/web-dubois-striving-negro/

Hansberry, L. (1961). A raisin in the sun. New York, New American Library

Harrell, K. (2020). Review of Black Lives 1900: WEB Du Bois at The Paris Exposition. Cartographic Perspectives, (96), 88-91.

Hartman, S. (2020). Wayward lives, beautiful experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. National Geographic Books.

Holloway, T. J. (2023). Unraveling the Block: DuBois, The Seventh Ward and Our Responsibility. Teachers Institute of Philadelphia. https://theteachersinstitute.org/curriculum_unit/unraveling-the-block-dubois-the-seventh-ward-and-our-responsibility/

King, M. L. (1968). I have a dream. Negro History Bulletin, 31(5), 16.

Low, S. (2016). Spatializing culture. December.

Miller, A. (1996). Death of a Salesman: Revised Edition. Penguin.

Moon, Jeannette (2023) What is Home? Teachers Institute of Philadelphia. https://theteachersinstitute.org/curriculum_unit/what-is-home

Rudwick, E. M. (1957). The Niagara Movement. The Journal of Negro History, 42(3), 177-200.

Weiss, C. (1995). New approaches to evaluating comprehensive community initiatives. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute. Retrieved from.

Yau, L. Y. K. (2023) WEB Du Bois and the Making of Accordion Books, Data Portraits, and People Places. Teachers Institute of Philadelphia. https://theteachersinstitute.org/curriculum_unit/w-e-b-du-bois-and-the-making-of-accordion-books-data-portraits-and-people-places/

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 19.7 KB | |

| 42.22 KB | |

| 27.19 KB | |

| 33.21 KB | |

| 159.68 KB | |

| 681.48 KB | |

| 443.12 KB | |

| 578.3 KB |