Teacher Inquiries into Poetry, Translation, and Literacies: Erica Darken, Lisa Yuk Kuen Yau, Mark Hauber, & Jie Park

This collaboratively authored piece highlights Poetry Inside Out, a poetry translation program that creates new pathways for culturally and linguistically sustaining literacy education. In Poetry Inside Out, students collaborate to translate world-class poems from their original language (e.g., Spanish, Chinese) into English. Informing PIO’s design is the view of translation as an interpretive and creative act and a form of close reading. Drawing on their own and each other’s linguistic and cultural repertoires and using a carefully scaffolded translation tool, students come to a deeper understanding of how languages and literacies work, paying keen attention to vocabulary, poetic form, syntax, grammar, rhythm, sound, and other nuances of the source and target language. Highlighted are two 5th-grade teachers’, Erica Darken and Lisa Yuk Kuen Yau, and their multilingual students’ engagement with Poetry Inside Out. Also highlighted are the teacher’s use of allied practices such as Accordion Books and dialogic talk.

Imagine you are an emergent bilingual child learning English in a typical classroom. Imagine struggling to understand and be understood by your classmates and teachers. You feel broken whenever you attempt to use your budding English but are interrupted and corrected. You feel overwhelmed and confused by school assignments. You, like most emergent bilinguals learning English, are told to “follow the rules” and rarely encouraged to ask “why” and “what if” as you study this new tongue, so instead you sit quietly.

Now, picture being an emergent bilingual in a different classroom, one that is filled with enthusiastic multilingual learners who clamor to be educated differently, asking their 5th-grade teachers, Erica Darken and Lisa Yuk Kuen Yau, to teach them English and literacy through translation: “When will we do translation again? Can I choose the next poem to translate [into English]? Why did we translate only four poems the whole year?” You join in the conversation, and ask to translate a poem from your own home language.

This collaboratively authored piece highlights Poetry Inside Out, a poetry translation program that fosters the development of emergent bilingual youths’ multiple literacies – the many ways of meaning-making and communication that are socially and culturally meaningful.. After explaining the design of Poetry Inside Out and our understanding of literacy and literacies, we highlight Erica and Lisa’s classrooms, offering examples of how Erica and Lisa each leverage PIO in their classrooms.

Description of Poetry Inside Out

Developed at the Center for the Art of Translation, Poetry Inside Out (PIO) is a language and literacy-rich program centered on poetry translation and its allied practices, including discussion and collaboration with peers. In PIO, students translate poems from around the world in their original language (e.g., Spanish, Vietnamese, Russian, etc.) into English. Informing PIO’s design is the view of translation as an interpretive act and a form of close reading. By practicing the art of translation, students come to a deeper understanding of how languages and literacies work, paying keen attention to not only meaning in context but also vocabulary, poetic form, syntax, grammar, rhythm, sound, and other nuances of the source and target language. Drawing on their own and each other’s linguistic and cultural repertoires, students in PIO build an original version of the text by moving back and forth between multiple languages, considering the whole poem against its words and phrases. Translation makes it evident that meaning is not found by deciphering individual words but by unraveling and restitching the entire vision of a poem.

In PIO, a translation is produced collaboratively, with students working together, first in pairs and then in groups of four. This makes talking and listening essential to PIO. By talking and listening, students develop their capacity to communicate ideas, positions, perspectives, and deeply personal stories connected to the poem’s theme(s); in the same sense, students learn to listen and listen to learn. This emphasis on talking and listening is the foundation for building meaningful collaborations. An additional fundamental principle of PIO is culture-building. For students to collaborate with peers on a work of consequence and engage in productive struggle, classrooms need to be spaces of inclusion and belonging, with an authentic appreciation for each other’s experiences, knowledge, and skills. Culture-building recognizes that each student draws upon imagination, existing wisdom, linguistic and cultural knowledge, and personal experience. All experiences and identities are relevant in PIO.

PIO encourages a gradual, cumulative approach to learning. Teachers are encouraged to go slow. Completing a single poem's translation may take several class sessions. It is better to go deep, taking all the time needed to understand a word, idea, image, or sense: this is what we mean by “close reading.” Attempting to cover as much material as possible can diminish the process and weaken the outcome. This process, or “close reading” of the poem, allows for conversations to emerge, tangents to be explored, and rich discussions and discoveries to occur. Students are encouraged to contribute their ideas about transferring meaning into a new language.

Students’ translations are shared and made public. Individual or group translations are read in front of the class or presented as part of an anthology or multimedia project. The idea is for students to make public what they’ve learned, gain mastery, and apply it. Students grow to see themselves and fellow students as masters of their languages, as poets, and as world citizens. One key question teachers ask is how multilingual students can translate poems in languages they do not know? Students can produce translations through a carefully scaffolded translation tool called the Poem Page. The “Poem Pages” contain all the essential materials necessary for translation. Every “Poem Page” contains 8 essential components:

| 1 | The poem in its original language |

| 2 | A portrait of the poet or an image related to the poem |

| 3 | A brief biography of the poet |

| 4 | A “Translator’s Glossary” |

| 5 | A “Phrase by Phrase” workbook page |

| 6 | A “Make It Flow” workbook page |

| 7 | A “Reflecting and Finding the Meaning” page |

| 8 | A page that offers background information |

We also include images of a Poem Page packet outlining these 8 essential elements:

While translating a poem, students follow a structured protocol called a Translation Circle. In the first step of the protocol, students become acquainted with the poem and poet’s biography. The teacher and students work together to identify critical parts and information on the first poem page, including the poet's name, country of origin, dates they lived, the language of the poem, poetic form, and the poet’s biography. In unpacking the poet’s biography, teachers may ask students to underline sentences or phrases that seem interesting, relevant, or confusing. Then, students will read the poem aloud to the whole class.

Next, the students, in pairs and with the “Translator’s Glossary,” work on a “phrase-by-phrase” translation. The “phrase-by-phrase” translation is akin to a rough draft, the first attempt by students to work with the language and meaning of the poem. Once students have completed their “phrase-by-phrase” translations, they work in groups of four to construct a “make-it-flow” translation. The two pairs have to reach a consensus. Their conversations are generative. In addition to word choice and meaning, they decide whether or not to follow the form, rhyme scheme, and even musicality of the poem in its original language.

Once all the groups have constructed their “make-it-flow” translations, each reads or performs their translation. Sometimes, they insert movement, dance, and visual art when sharing their translations. Each reading or performance is followed by appreciative “ahs” and finger snaps. Then, the teacher facilitates a whole-class discussion in which students explore possible meanings of the poem, identify words or phrases that were particularly difficult or interesting to translate, notice similarities and differences across the translations, and offer different rationales behind their translation choices, drawing on their full linguistic repertories, cultures, and background knowledge.

Conceptualizing Literacies in the Context of Poetry Inside Out

Each step of the Translation Circle is designed to simultaneously leverage and enhance students’ full linguistic repertoire and literacy capacities. We see literacy as extending beyond reading and writing skills and as a sociocultural practice that everyday people engage in, create, and transform. We see literacies as plural – the multiple ways of meaning-making and meaning-sharing that are creative, personally, and culturally meaningful. Literacies are situated in contexts (e.g., families, neighborhoods, institutions) and shaped by our social identities, ideologies, and power relationships (Gee, 2015; Street, 2013). We also see literacies as a way of understanding and transforming texts (written texts, multimodal texts) and the world. As such, literacy is a critical practice in the Freireian sense of the “word-world” relationship (Freire, 1983). Finally, we see literacies as enriched by multilingualism and multilingual classrooms. Unlike monolingual, English-only frameworks, multilingualism sees multiple languages in a shared space (and as part of a person’s linguistic repertoire) as a “normal condition” and “resource for learning” (Meier, 2017, p. 155). Learning is understood as a collaborative, multilingual activity, and teachers are positioned as language learners, not experts.

Poetry Inside Out Teacher Fellowship Program

Erica and Lisa are members of the inaugural cohort of the PIO Teacher Fellowship Program – designed and facilitated by Mark, PIO’s program director. Working alongside teachers and youth in Worcester, Massachusetts, Jie has documented the impact of PIO in multilingual classrooms (for an example, see Park et al., 2015). Mark invited Jie to join the Fellowship Program in an advisory role, supporting teachers like Erica and Lisa in their practitioner inquiries.

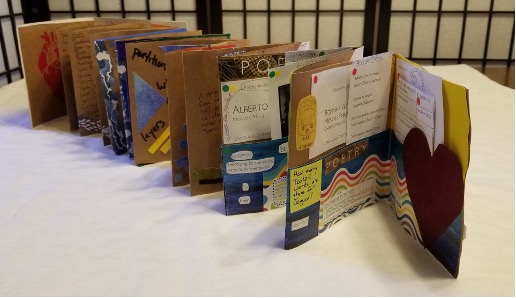

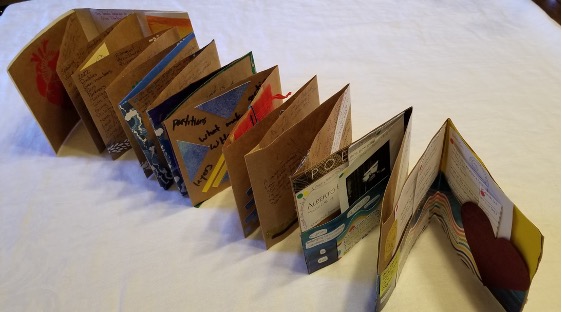

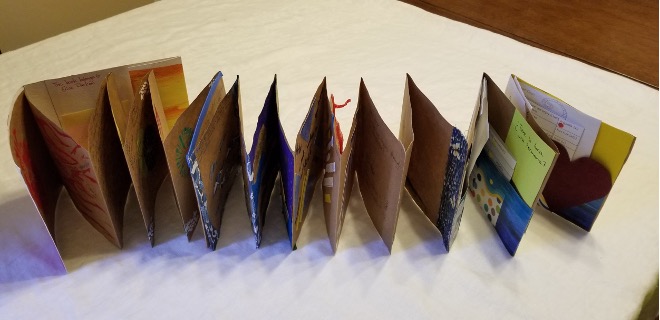

During their time as PIO fellows, participating teachers deepen their understanding of PIO and its allied practices that foster students’ literacies and identities, as well as their creative engagement and critical skills. Teachers are also supported to incorporate source materials in multiple languages and implement reflective teacher practice and arts-based pedagogy, principally through Accordion Books (for a description of Accordion Books see Elkin & Mistry, 2018). Todd Elkin and Arzu Mistry guide PIO fellows in creating and maintaining Accordion Books, which have a single page that can be folded, unfolded, and appended, as a method of documenting and reflecting upon teaching practice. Finally, the fellows learn about translation and poetry, digging deeper into their philosophies and experiences with translation and poetry to integrate them into their teaching of subjects ranging from art and ELA to science.

Photos with side, angle, and bird’s eye views of Erica Darken’s Accordion Book, expanded to reveal written reflections, collage, and poetry artifacts in pockets.

With monthly meetings and the support of colleagues and advisors, the Fellowship Program operates as a practitioner inquiry community. A central component of the Fellowship Program is practitioner inquiry, or the time set aside for intentional and systematic documentation and reflection on teaching and learning (Ballenger, 2009; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2015). Practitioner inquiry is a methodology and an epistemological stance grounded in critical and democratic social theory. Practitioner inquiry positions teachers as public intellectuals and knowledge generators. It assumes that “local understandings, observations, and insights [of practitioners] can accumulate knowledge of critical importance to the challenges and problems at hand” (Lytle, 2008, p. 375). In the next section, we (Lisa and Erica) offer reflections on our students, ourselves (as educators and language learners), and teaching literacies from our practitioner inquiries.

Teacher Inquiries into Literacy

Erica’s Classroom (Erica)

I have the felicity of teaching in a culturally and linguistically diverse elementary school in South Philadelphia. My students’ primary home languages include English, Spanish, Nepali, Burmese, Chinese, Swahili, and Vietnamese. As a bilingual[1] individual who is striving to become trilingual, I relish exploring aspects of language with students. Poetry Inside Out is one of the practices that motivated me to return to the classroom after several years in the central office.

PIO is horizon-broadening for all students, regardless of their home language. Students are excited to work with a language they have a connection with and are also excited on behalf of their classmates. When I introduced a poem in Vietnamese, my 4th graders enthusiastically said, “Vinh, your language!” I’ve also had a native English speaker tell me she wanted to learn Spanish. Over the years, as I’ve worked with 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders,[2] language remains my primary motivator when choosing a poem, though themes and poetic devices matter, too. Language selection considerations include the familiarity versus novelty of a language for my students, the language proficiency of my students in English and the source language of the poem, and the script and language families of the source language.

I pay a lot of attention to developing metalinguistic awareness in my students. As defined by Beeman & Urow (2013), metalinguistic awareness is “the process of consciously making connections between languages and bridging from one language to another language.”[3] These connections include similarities and differences in word parts, word order, and spelling patterns. I also want my students to realize the power that cognates (words related by derivation) have to unlock meanings across languages, such as words derived from common Latin roots. For example, Spanish speakers can apply knowledge of these roots when encountering new words in Romance languages like Portuguese or French, as well as with Latin-derived words incorporated into English. As a beginning Gujarati learner, I’ve also begun to learn the power of cognates across languages derived from Sanskrit, such as Gujarati (ગુજરાતી), Hindi (हिन्दी), and Nepali (नेपाली).

I strive to guide my students to value languages written in other scripts besides Latin letters. Almost every year, my students translate a poem into Japanese to begin to demystify character-based languages. I’m also working with fluent Gujarati collaborators to create a poem page in Gujarati to open the door to Indian and other South Asian languages in the PIO archive. When I taught third grade, I had six Nepali students, one of whom regularly wrote her name in Devanāgarī script at the top of her work. Imagine if I’d been able to present that class with a poem in her script, let alone her language. What confidence and joy would she experience? What insights could she share with her classmates?

Another part of my teaching philosophy that aligns with PIO is collaboration. I always have students sit in pods of four or in pairs that effortlessly combine to make pods when needed. This desk configuration allows students to work together for science experiments, group activities in math and language arts, and, of course, as a classroom teacher during PIO. I make these groups heterogeneous, though there is often a language buddy for emerging bilingual students within the partnership or quad. I do many community-building activities and clarify to students that they need to learn to work together even if they aren’t best friends and that if someone rubs them the wrong way, they need to work through it, with teacher guidance as needed. Students generally accept this as fair, though they remind me when the new quarter begins that it’s time to change their seats. While I changed partnerships within that time, I don’t recall ever having to change quads off-schedule after the school year was in full swing.

Collaboration promotes literacy by pooling student strengths to create a translation greater than the sum of its translator’s phrase-by-phrase versions. When preparing the linguistically heterogeneous groups for translation, sometimes a student will say, “But I don’t know Spanish,” which is the perfect prompt for me to point out the linguistic and academic strengths of the students in the group; one student might bring more confidence with English, another with Spanish, a third with the subject matter, and a fourth with poetic devices and metalinguistic awareness. They gain intercultural communication skills by working in these groups. In fact, collaborative translation is implemented outside the classroom as well, as described by Bellos (2011):

Knowing two languages extremely well is generally thought to be the prerequisite for being able to translate, but in numerous domains, that is not actually the case. In the translation of poetry, drama, and film subtitles, for example, collaborative translation is the norm. One partner is native in the “source-text language,” or L1, the other is native in the “target language,” or L2; both need competence in a shared language, usually but not necessarily L2 (p. 66).

Together, students can create a richer translation than any is likely to do individually, not only because of their combined strengths but also because of the ideas generated during their academic conversations.

Many of the synonyms in the translator’s glossary are new words for my multilingual learners, who often do not know the nuances of each one. They also need support in articulating their word choice to their classmates. To support them, building off the work of Zwiers et al (2014), I created a chart with sentence starters and reasons a word might work better in a poem. This support is also useful in whole-class, linguistically heterogeneous settings that include native English speakers and experienced English language learners.

| Sentence Starters | Reasons |

|

I chose the word _____ because… I think _____ sounds better than _____ because… I think _____ looks better than _____ because… I think _____ flows better than _____ because… I think _____ makes more sense than _____ because… |

…it means… …I think the poet wanted to say… …it has alliteration with the word…. …it rhymes with… …it repeats the way I/we translated… …it doesn’t repeat the way I/we translated… |

Chart with sentence starts and reasons to support student discussions when they defend their translations.

In the 2021-2022 school year, my fourth graders translated two Japanese poems: Furu ike ya by Matsuo Basho then Koko ni nomi, by Sei Shonagon, which tied in thematically with the poem Dust of Snow by Robert Frost. Students then advocated for another translation, and for the third translation, which would be our last that school year, I gave them a choice among four poems in four languages: Spanish, Vietnamese, Portuguese, and Tzotzil. To use Bishop’s (1990) metaphor of windows, mirrors, and sliding doors[4], the student choices seemed to reflect a significant desire for linguistic mirrors to contemplate their own heritages or windows to view their friends’ linguistic world: 9 of my 12 Spanish speakers chose the poem in Spanish, and 4 of my 6 Asian American students, including one Vietnamese speaker, chose the poem in Vietnamese. One student chose the Portuguese poem, though her second choice was the Spanish poem, so she had a group to work with. The 4 students who chose the Tzotzil poem were a mix, including 2 Spanish speakers[5], one Asian American student, and one white monolingual student.The choice of the Tzotzil poem could be described as either a window into a previously unknown language and culture, or even a sliding door that can be opened for the student to join this new environment Here is a sample of their work, originally handwritten and then typed by the students in the font styles and purple, pink, and red as follows[6]:

Screenshot of a collaborative student translation of the poem Bolom Chon with the original text in black and the translated lines in red, pink, and purple.

Poetry Inside Out has made me more flexible and humble as a language teacher. Both adults and children can become invested in their original interpretations and phrase-by-phrase translations. The first time I participated in a PIO translation circle during a Philadelphia Writing Project Workshop in the summer of 2015, I liked my initial translation and resisted collaborating with my partner and quad. The translation of a second poem was easier, and now I tell my students what I told myself to be able to let go of stubbornness: Your first version still exists; you are also going to be able to create another collaborative version that has the best of every group member’s ideas.

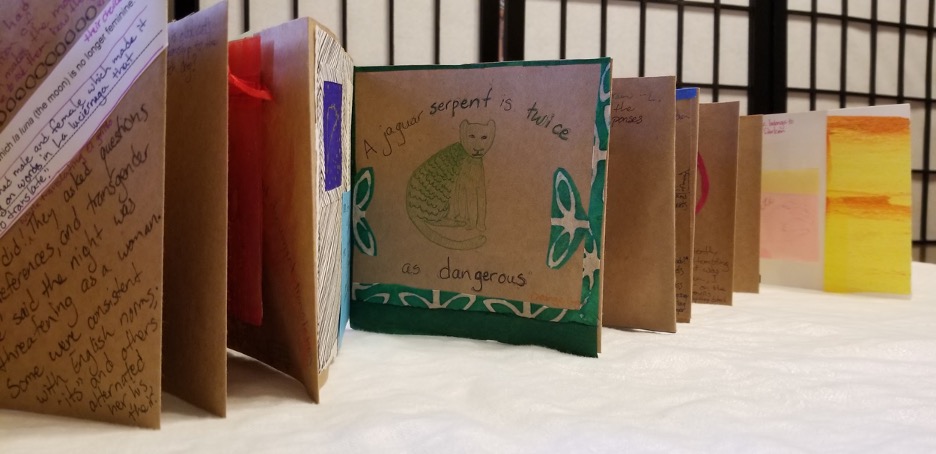

My Accordion Books have been a vital medium for documenting and reflecting on my ideas and those of my students. The first time I translated the Tzotzil poem Bolom Chon, I was very sure that since bolom means “jaguar,” “dances” would be the better translation of chon, so that the phrase would be “jaguar dances,” as my 4th graders translated the line, not “jaguar serpent.”

Excerpt from the translator’s glossary for Bolom Chon.

However, upon researching Mayan beliefs, I learned about the importance of Kukulkan, a Mayan deity often represented as a feathered serpent and sometimes linked to other animals, including the jaguar. My fifth-grade students didn’t need this background information from me; some quickly saw the power of the combined jaguar serpent, whose danger was multiplied. My first Accordion Book has my illustration of the jaguar serpent, with the student quote.

Photo of a page in Erica Darken’s Accordion Book with a drawing of a jaguar serpent and the quotation, “A jaguar serpent is twice as dangerous.”

PIO is a powerful living archive of possibilities for students to experience language windows, mirrors, and sliding doors. Students have the opportunity to see their own language reflected back to them with all the beauty and creativity of a poem, peer into their classmates' linguistic spheres, and step through doors to new language proficiencies. Throughout these processes, with intentional guidance, students develop their literacies as translators, negotiators of meaning, and cross-cultural team members. Students and teachers enhance their understanding of the world from the words of poets and the classroom community.

Lisa Yuk Kuen Yau’s Classroom (邱玉娟的教室)

PIO has a unique quality that leads students to be fired up, hungry, and curious about the word-world (Freire, 1983). Throughout my eight years of using PIO in my classroom, the program has provided me and my students with multiple learning opportunities and new pathways of teaching that are culturally responsive, language-inclusive, worldly relevant, and soul-inspiring. More amazingly, in the quest to discover the world, my students (both monolingual and multilingual) have discovered themselves as creative “readers by writing and translating.”

In addition, PIO brings people of different origins and generations together. In my first year of teaching with PIO, I was fortunate to have Jessica Tyson, a PIO practitioner from California, visit my 5th grade classroom and support me. The most memorable translation was a “sung poem” titled “Đơn Sơ” by the Vietnamese poet Lê Phạm Lê (1950 -) – a poem that my students selected. My students were fortunate to have two native Vietnamese speakers who were also in-school teachers, actually a husband and wife team, came to my room separately, and read aloud the poem in Vietnamese. The male teacher’s reading exerted strength and purpose, while the female teacher’s reading sounded like a sweet lullaby with rising and falling rhythm. The class discussed how different the two readings were, and how one person may interpret the same poem very differently from another person. Because poetry is an oratory art with sound and rhythm, it is important to read a poem out loud and multiple times. In addition, the class did a deep dive into the Vietnam War, how a “monkey bridge” (lắc lẻo nhip cầu in Vietnamese), a traditional Vietnamese handmade bamboo bridge, can stand for the journey of refugees escaping the brutality of war, as well as a link connecting two worlds. For one of my students, a Vietnamese-American, translating this poem by a Vietnamese poet reminded her of her family and their struggles as refugees, and she was able to go home and share this experience of translation with her parents.

Simple As Done

Lost in the land

Building a house near a forest full of water

All the different rock on the ground

Hard and Soft

In the night the moon reflects its light

Through the shadow

Sleeping on the cold ground

While mothers sing a lullaby for those who they love most

At the morning bridges full of monkeys

Many ship sail while others are sinking

At the bottom of the ocean

The wind blowing freely

Bring my spirit back up

—translated by a fifth-grade PIO student

https://www.catranslation.org/blog-post/sung-poetry-and-the-art-of-listening/

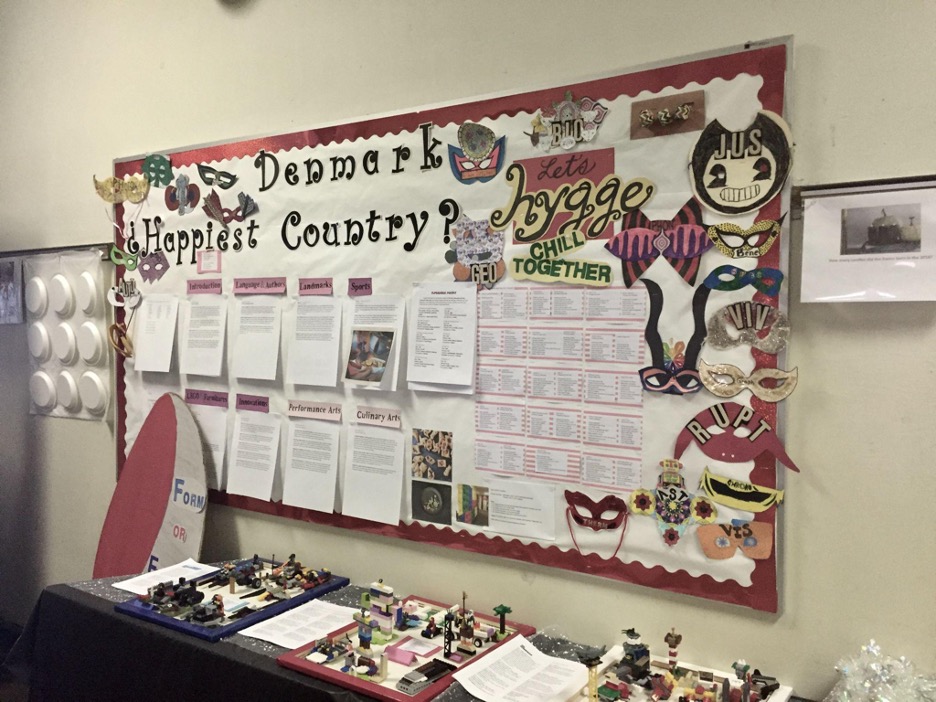

With PIO, every year, I’ve learned something new because each year, my students steer the ship and identify which world languages the class will translate. During the first year, besides the poem “Đơn Sơ” by Lê Phạm Lê, the class also learned about the Japanese philosophy of Zen Buddhism and the wisdom of emptiness while translating a haiku by Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉) about a frog jumping into a pond. In my third year of PIO, my class translated a Danish poem that led to a full-blown investigation about Denmark, why Denmark is purported to be the happiest country in the world, the obsession with hygge (getting cozy), smørrebrød (open sandwiches), and the story of the Little Mermaid, and Lego (translated as “play well”).

Photo: A bulletin board display of creative learning after translating the poem Hviskende Græsfødder by Inger Christensen (1935–2009) of Denmark.

A few months before the COVID-19 pandemic, I noticed a sudden change of mood in two of my students, who are cousins. One was absent more than usual, even though he lived less than a block from school. Later, I found out that his family was in the process of moving to Harrisburg, where there is a thriving Southeast Asian community. It also just so happened that the class chose the Malay poem “Tenang Telah Membawa Resah” by Latiff Mohidin (1941–) for our following PIO translation. The students’ families were Myanmar’s nationalists who fled to Malaysia and later immigrated to the United States. Though Burmese, Malay, Nepali, and Thai are four distinct languages, this student read the Malay poem with excellent command. When I challenged the class with tongue twisters from around the world, he naturally excelled in reading Romanized tongue twisters from Thailand and Nepal with similar ease.

In my 8th year teaching PIO, I was challenged with how little I understood the Russian language. Nova (age 10), a nickname she gave herself, surprised their classmates and me with “I was born in Russia. I think it was Moscow. But I don’t know.” My immediate reaction was: “Please, ask your parents tonight.” A month later, I selected the Russian poem “Поэты (Fragment) POET” by Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941) for our second round of PIO. The class and I were motivated to learn more about Russia and the Russian language thanks to Nova. My students struggled to read the Russian poem. Though it was complex to read and intense in meaning, the class was open to the challenge because we knew how much it meant to Nova. While viewing a YouTube reading of the poem by a native Russian speaker, students had various reactions: “It’s so dramatic, like in the theater.” “Is she acting?” “Why is she so angry?” “She is passionate about the poem.” The class talked about stereotypes of Russians, and we discovered that smiling at a stranger is often regarded as insecure in Russia.

The Romanian avant-garde poet Tristan Tzara (1896-1963) was one of the central figures of the Dada, an anti-establishment art movement after 1914. His instruction for “To Make a Dadaist Poem” (1920) is closely related to PIO’s impact on students. Tzara gave the following instructions:

“Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd..”(Tzara, 1920, n.p.)

Contemporary poets are unafraid to challenge the language norm, ask why, and propose something new: make new “what is old” and “what is new just a moment ago.” When students translate a PIO poem from a language other than English, they read that language by writing in English; they create something new based on the original. The poet Ron Silliman uses the technique of parataxis to juxtapose two or more fragments (word phrases) to make what he calls “the new sentence.”

Similarly, PIO challenges students’ assumptions about the rules of languages and allows them to create their connections and forge pathways for something new with English. For young readers and writers like my 5th graders, PIO is a combination of the Danish word smørrebrød (butter and bread), the Greek word kaleidoscope (beautiful shape to look to), and the Buddhist philosophical teaching of Śūnyatā (emptiness). Students are presented with a table full of open invitations from around the world, while looking through a stained-glass window of beautiful colors, and asked to put their creative thinking collaboratively on a map of possibility.

Conclusion

Through Lisa and Erica’s classrooms, we see how multilingual students use literacy to develop new insights and knowledge about themselves, each other, and their social worlds by translating poetry from around the world. Moreover, through close reading, writing, and talk, students communicate experiences, explore ideas and the function of language (e.g., metalinguistic awareness), and grapple with social and personal issues. This is done across multiple cultures and languages, including students’ home languages, discourses, art, and gestures.

Lisa and Erica also positioned themselves as learners, not just of their students, but of languages and literacies. As teacher researchers, Erica and Lisa saw themselves and their students differently and with greater clarity and created new classroom worlds that center creativity, openness, and multiplicity.

[1] One of whom did not end up participating in the translation due to extensive absences.

[2] Pseudonyms have been substituted for student names, and the work has been reformatted to be single-spaced.

[1] My first language is English and I learned Spanish in middle and high school, college, and beyond.

[2] This last grade as an ESOL teacher in both small group and whole class settings.

[3] Beeman, K. and Urow, C. (2013). Teaching for Biliteracy: Strengthening Bridges between Languages. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon Publishing. As cited in: School District of Philadelphia, Office of Multilingual Curriculum and Programs. (2024: 3) Welcoming and Incorporating Home Languages (L1) as a scaffold. Unpublished internal district document.

[4] More recently, Debbie Reese added curtains for the times when members of a culture want to keep knowledge of certain aspects of their culture within their community (Reese, 2018).

[5] One of whom did not end up participating in the translation due to extensive absences.

[6] Pseudonyms have been substituted for student names, and the work has been reformatted to be single-spaced.

Ballenger, C. (2009). Puzzling Moments, Teachable Moments: Practicing Teacher Research in Urban Classrooms. Teachers College Press.

Bellos, D. (2011). Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Faber and Faber, Inc.

Bishop, R. S. (1990, March). Windows and mirrors: Children’s books and parallel cultures. In California State University reading conference: 14th annual conference proceedings (pp. 3-12).

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2015). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. Teachers College Press.

Elkin, T., & Mistry, A. (2018). The Accordion Book Project: Reflections on Learning and Teaching. In T. Chemi & X. Du (Eds.), Arts-based methods in education around the world (pp. 107–151). River Publications.

Freire, P. (1983). The importance of the act of reading. Journal of Education, 165(1), 5–11.

Gee, J. P. (2015). The new literacy studies. In The Routledge handbook of literacy studies (pp. 35-48). Routledge.

Lytle, S. L. (2008). At Last: Practitioner Inquiry and the Practice of Teaching: Some Thoughts on" Better". Research in the Teaching of English, 42(3), 373-379.

Meier, G. S. (2017). The multilingual turn as a critical movement in education: Assumptions, challenges and a need for reflection. Applied Linguistics Review, 8(1), 131-161.

Park, J. Y., Simpson, L., Bicknell, J., & Michaels, S. (2015). When it rains a puddle is made”: Fostering academic literacy in English learners through poetry and translation. English Journal, 104(4), 50-58.

Reese, D. (2018). Critical Indigenous Literacies: Selecting and Using Children’s Books about Indigenous Peoples. Language Arts, 95(6), 389-393.

Street, B. (2013). New literacy studies. In Language, ethnography, and education (pp. 27-49). Routledge.

Zwiers, J., O'Hara, S., & Pritchard, R. (2014). Common Core Standards in diverse classrooms: Essential practices for developing academic language and disciplinary literacy (1st ed.). Routledge.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 176.92 KB | |

| 94 KB | |

| 132.71 KB | |

| 46.14 KB | |

| 48.38 KB | |

| 53.18 KB | |

| 168.83 KB | |

| 32.07 KB | |

| 91.93 KB | |

| 189.69 KB |