A Sankofian Approach To Applying Self-Determination Theory In Schools: Centering Teacher and Student Motivation in Culturally Responsive Lesson Planning

This article describes a piloted approach to responsive lesson planning and lesson reflection that centers the motivation of both teachers and students in public school settings. Anchored in the African philosophical approach of Sankofa and Self-Determination Theory, the tools and practices described encourage strategic reflection while considering the basic psychological needs of both children and adults. Special Education teachers in Washington, DC employed a Lesson Internalization co-planning tool and found it aligned the paired teachers and filled gaps in the social-emotional and support needs for their students not captured by traditional lesson planning formats. General education teachers in the Bronx utilizing a responsive post-lesson reflection tool were able to adeptly pinpoint problem areas in delivered lessons, identify differences in causes of struggles between different sections of students, and even replace a traditional approach to behavior intervention for a student. Crucially, the practices were found to be fully internalizable and did not unduly add to the planning or reflection workload or time commitment for the teachers. The successes found in these pilots suggest the potential for a broader application of motivation-centered approaches in other aspects of school including conflict resolution, teacher evaluation, coaching, hiring practices, and professional development.

Introduction

Reams of research and professional development materials have been printed extolling the value, virtue, and impact of responsive and humanizing education for students, but these ideas are rarely extended to the development and coaching of new teachers. Whether it is in planning, delivering, or reflecting on lessons, practices and perspectives tend to focus only on students and progression, omitting the human elements and responsive needs that the teacher brings into the room. While a wide variety of planning models and practices exist across schools, most approaches encompass only the depth and breadth of content and any modifications or accommodations. Any responsive elements of the lesson planning protocols are typically only considered from student perspectives. While the reasonable expectation in 21st century teaching reflects an understanding of the fact that students learn in different ways and demonstrate mastery through different modalities, that same flexible understanding rarely extends to teachers, who are typically expected to plan, deliver, and reflect on lessons in rigidly similar ways.

Teachers today are challenged with navigating and orchestrating complex learning spaces that expect them to educate the “whole child.” This includes taking into consideration the entire sociocultural learning context that influences a child’s development at various stages of their life. While this task can seem unrealistic, the reality is that teachers will have to refine, reimagine, and reflect on the ways they plan their lessons in addition to considering what impacts the motivation of the “whole teacher.” It is particularly critical to refine these practices in light of the neoliberal accountability demands of school leaders to increase test-scores, but also due to the current climate of book bans, war on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), and anti-critical race theory (CRT) rhetoric that is dominating the conversation and decisions within today’s “post-pandemic” educational institutions.

Setting and Context of Pilot Study

The lesson planning tools were employed in two settings for this pilot study: an integrated co-teaching special education teacher employed the planning and real-time data collection in a traditional public elementary school in Washington, DC and four general education subject area teachers (two ELA, one Social Studies, and one Science) used the reflection tools in a public charter middle school in the Bronx. While both the coach and teacher in the DC Public School setting were traditionally prepared and certified, such was not the case for the teachers in the Bronx. Three of the Bronx middle school teachers teach sixth grade and all four joined the school from either KIPP or Success Academy, two large charter school networks that use strictly prescribed curricula, lesson plans, pacing, and classroom structures.

All four participants expressed a desire for more autonomy in their teaching and a lack of perceived competence in their prescribed previous settings. Both autonomy and competence are basic psychological needs in self-determination theory. Despite their desire for autonomy and to demonstrate their competence, the three sixth grade teachers, who are also younger and less experienced than the fourth teacher, demonstrated significant deficit mindsets toward their own teaching abilities that is likely a result of their previous setting’s rigid structures being replaced by more expansive flexibility at their current school. Additionally, however, having the flexibility to structure their classes and materials more authentically in their new teaching environment necessarily included some trial and error that also contributed to perceived deficits in their own practice. The reflection practices employed with their “thought partner” helped to reframe those feelings of inadequacy into data collection activities to improve practices. Though each teacher structures their classes and delivers their lessons in radically different ways, they all find utility in the human-centered approach of the reflection materials.

Description of tools used for pilot study

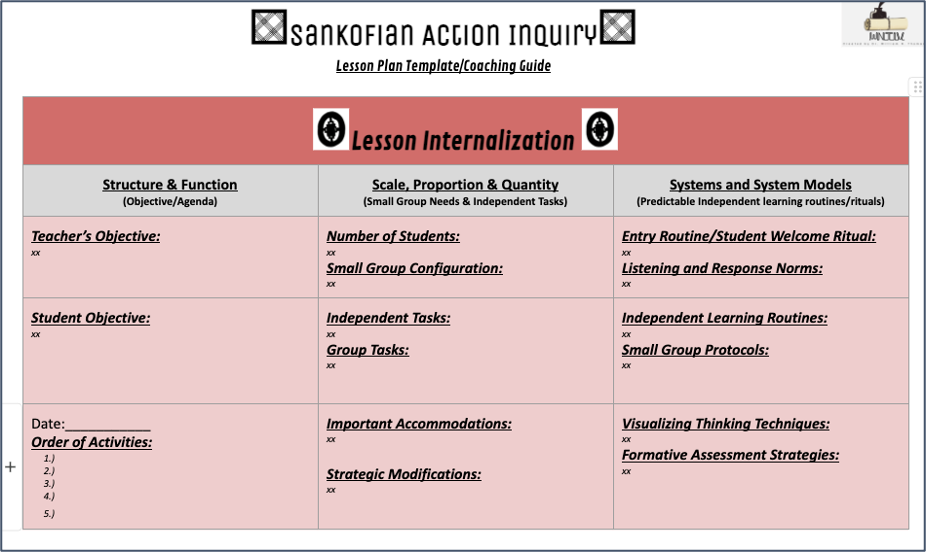

The data tools package includes three separate collection and reflection elements: a lesson planning/coaching internalization guide for pre-lesson work, a real-time data collection tool for observation or priming reflection work, and a post-lesson critical reflection model (Appendix B). Because the participants in this work already had preexisting relationships and targeted areas for development, the DC Public School and Bronx middle school interventions employed only the pre-lesson internalization guide and post-lesson critical reflection tools, respectively. The lesson internalization planning tool has aspects requiring teachers to consider many elements of a class that are typically not included on traditional planning templates but are practiced by experienced teachers such as entry routines, a separation between objectives for students and teachers, an overt separation between accommodations and strategic modifications; and visualizing thinking techniques. These considerations can help neophyte teachers include elements of more seasoned teachers’ practices and also catalyze cohesion between new teaching/collaboration partners when they begin sharing a classroom setting.

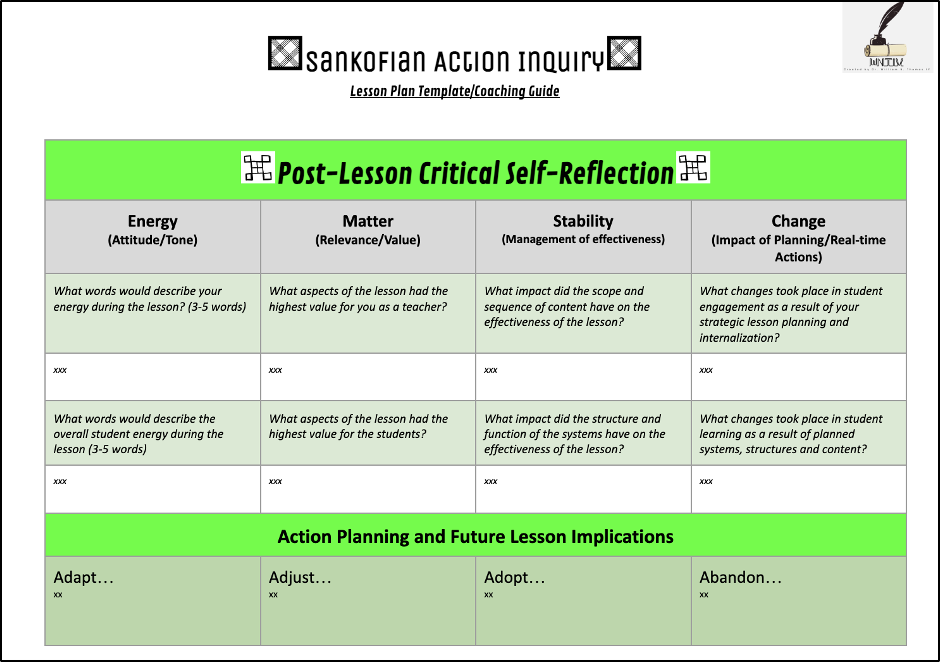

Similarly, the Post-Lesson Critical Reflection departs from most typical lesson reflections that either focus on what students/teachers did during the period or time stamps of when the lesson went off the rails or could benefit from intervention. Rather, this tool takes a more macro view by evaluating the lesson on considerations of Energy (attitude and tone) both of the teacher and students, Matter (relevance and value) for both teacher and student, Stability (management and effectiveness), and Change (planned and real-time actions). The first two considerations, Energy and Matter, concern the teacher’s delivery, whereas the latter two (Stability and Change) analyze the teacher’s planning. In this way, the teacher is forced to view a lesson from an interactionary lens between all of the humans involved instead of simply through the traditional lens that centers the teacher and tacitly utilizes a banking view of teaching. Instead, teachers (and coaches) are analyzing the impact (delivery) and intent (planning) of their lesson both through perceptions of themselves and their students to evaluate their work. Conversations end with the teacher walking away with 4 “A”s from their reflection: those elements of their practice that they want to Amplify, Adjust, Adopt, and Abandon. While these conversations are lengthy at first, the protocol is intuitive enough that it can be easily employed for quick 30-45 second hallway check-ins on an everyday basis as well as for in-depth analysis after observations, co-teaching sessions, or particularly difficult lessons (see Appendix A for Lesson Planning Model and Appendix B for Lesson Plan templates).

Theoretical Framing

Sankofa epistemology and pedagogy

This study is anchored in the African philosophical approach of Sankofa and conceptualizes it as an epistemological and pedagogical (Small et al., 2020) approach to applying culturally responsive lesson planning for diverse learning populations. The Akan people of West Africa (Willis, 1998) symbolically depict this concept using the symbol of the Sankofa bird positioned in a way that shows while advancing, it is consistently and strategically looking back to the past to (re)contextualize and (re)conceptualize its future. Our application of Sankofa included a focus on the motivation that both the teacher and student bring to the learning environment. With the education system in the United States designed to value and glorify western philosophical notions of teaching and learning, it is important to rediscover the practice of recentering of African epistemology (African conception of the nature of knowledge) as a valuable source to gain self-knowledge and to promote community empowerment. Oftentimes, the African theory of knowledge is relegated to only specialized Afrocentric schools and not considered to be as valuable in traditional public or charter schools settings.

Integration motivation theory and culturally responsive teaching practices

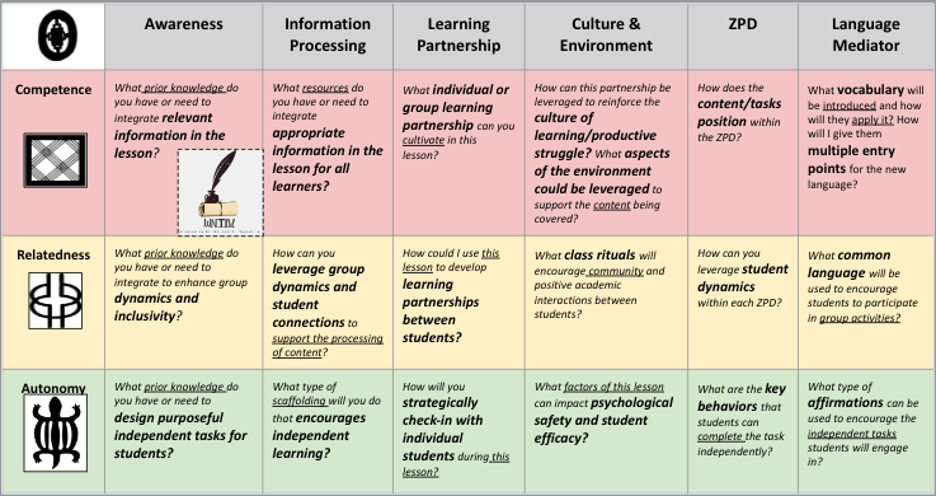

The culturally responsive lesson planning process included an emphasis on the basic psychological needs of both the educator and student through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Motivational awareness is the ability to identify specific psychological needs that both impact your motivation and define your purpose in a designated social space (Thomas IV, 2023). These needs include competence, relatedness and autonomy (Ryan and Deci, 2017). This means knowing what factors engage you in a way that impacts your body language, attitude and responsiveness to the environment. Motivational awareness is particularly important for educators and leaders as their multilayered experience with students, colleagues, leaders and families can cause many to feel a sense of burnout which eventually leads to them leaving the profession. This exodus, particularly with quality classroom teachers, leaves our students with incoherent and inconsistent images of dedicated educators who feel invested in their success. The intentional and critical examination of self-motivation, mirrors the archeology of self (Sealey-Ruiz, 2022) approach, which can be used as a way for educators to understand who they are within a school context.

Findings and Implications

Bronx Middle School Pilot Study

The teachers in the Bronx middle school added the post-lesson reflection tool both to their debriefing with their assigned coach (called a thought partner in that school) and in their individual weekly lesson reflections as part of their planning requirement. They found it to be useful in three distinct ways. First, the teachers found that the tool helped them quickly and effectively evaluate the level to which their teaching objectives “hit home” with both teachers and students in a particular lesson. In the times when they felt that the mark had been missed, the tool was useful in evaluating whether the issue was with their teaching delivery (which includes everything from their language to energy and connection to the material) or their planning scope and sequencing (including any modifications, accommodations, and look-fors). As such, they were able to efficiently pivot teaching strategies between sections of the same lesson or shift teaching in future lessons.

The teachers also found that the reflection tool was useful for discussing issues they were having with particular sections. Both the science and social studies teacher were having in-lesson transition issues with the same section of sixth graders, at the same time. They naturally assumed that there was some common practice that was causing this issue in their classes. After working through the reflection protocols, however, the two teachers found that these disruptions and interruptions were due to drastically different elements of their practices that were producing similar student responses during the lesson. An outside observer might have thought the same issue was at play due to the similarities in disruptions, however, the incidents required different teaching strategy modifications. This is not a conclusion they would have likely reached through traditional kid talk or reflection approaches but they were able to reach it quickly and respond through the facilitated reflection with this tool.

Finally, one teacher used an adapted version of the reflection tool in conjunction with the school’s social worker to have a behavior conversation with a student who was struggling to contain outbursts and feeling unsuccessful in their class. The teacher-based reflection tool was modified to reflect the student’s perception of their own, the teacher’s, and the rest of the class’ energy, considering when else they felt that energy, and the impact of their own and the teacher’s actions. In doing so, it moved the conversation with the teacher beyond disagreeing on each person’s respective intents and instead focused on the impact each had on the learning environment and perceptions of belonging. This conversation and reflection replaced the traditional Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP) approach, which typically relies on extrinsic motivation and external rewards, and resulted in a broad and deep understanding between the student and teacher about where their deficit-based, defensive perceptions of class and each other reinforced patterns that were unproductive. As a result, the teacher was able to create new systems in her class to address the needs identified by the student, and the student was able to generate a set of personal goals to find success in the class. Both gave feedback that the guided reflection conversation was much more fruitful than any other that had occurred between the two, and that the class has since improved drastically for both of them.

Implementing this practice in our coaching/thought partnership model required a significant leap of faith by both members of the partnership and the principal of the school, since it was a significant shift away from traditional practices. The ability to be flexible with the model employed for teacher development was likely influenced by the fact that the middle school is a standalone charter school and that the coach has been there for five years, accruing significant social credit with the leadership team in that time in terms of his development work with teachers. While all the educators involved expressed some wariness when the new reflection practices were introduced, all participants described significant growth in both impact and efficiency of their reflection on their lessons as the work progressed. What began as 30-40 minute conversations were often pared down to 3-5 minutes as both partners became comfortable with the tool and dialogue moves. Furthermore, self-diagnosis of issues with delivery of content or depth and breadth of planning was developed through the use of these tools and facilitated discussions.

DC Public School Pilot Study

The utilization of the Lesson Internalization tool in the collaborative planning of a lesson with both an expert special educator and a first year general educator proved to be valuable in various ways. Initially, it facilitated a clear understanding of the general educator’s objectives for the lesson, encompassing both the teacher and students’ goals, along with the sequential order of activities to achieve those objectives. This understanding not only enabled her to grasp the overall lesson structure but also offered insights into how she could provide effective support for students with disabilities. She was able to proactively prepare necessary aids before the lesson, such as reviewing vocabulary, crafting sentence starters, and previewing the text.

Furthermore, the use of the Lesson Internalization tool provided valuable insights into how you could support the general educator, particularly within the development of critical social-emotional systems within their lessons. This involved ensuring that norms, routines, and protocols effectively supported the communication skills of all learners. Drawing on her expertise as a special educator, she recognized the significance of developing norms that foster a sense of belonging, routines that contribute to emotional resilience, and protocols that promote engagement. The tool helped her gain a clearer understanding of how to contribute to the creation of a supportive and inclusive learning environment that addresses the diverse social-emotional needs of students.

In addition, this tool guided in identifying specific points throughout the lesson where support was needed for individual students. It provided clarity on how to assist both the entire class and those with learning disabilities during various activities. For instance, it indicated which partners might benefit from additional support during activities like think-pair-share, or which students required check-ins during independent work. This insight empowered her to be purposeful and intentional in the support offered throughout the lesson. Additionally, it guaranteed that appropriate modifications and accommodations were implemented during specific activities, ensuring that all students could effectively engage with and access each component of the lesson.

Conclusions and Considerations

Assuming a baseline of trust and familiarity, this approach to authentic, teacher-owned development reflection has broad application potential for principals, coaches, specialists, and teacher preparation programs. Developing teacher-owned reflection skills that cover both delivery and planning aspects builds a learning classroom and amplifies the autonomy and competence aspects of a teacher’s development without sacrificing the basic psychological need for genuine relatedness. Furthermore, having facilitated dialogues between more- and less-experienced teachers or even between teachers and administrators drives feedback that is more actionable, personalized, and frequent than annual and semi-annual evaluations. For teacher preparation programs, this system of tools creates a development environment that allows for non-technical refinement of practices and authentic teaching practice as well as modules that could easily be adapted for classroom observations, student teaching, or mentor relationships.

This collaborative planning tool serves as a resource that can be used by various educational stakeholders, including principals, coaches, specialists, and teacher preparation programs. Principals can adopt the Lesson Internalization tool as a standardized collaborative lesson plan template for the entire school, ensuring that all lessons are designed to be inclusive of diverse learners. Coaches can use the tool to assess and provide support for teachers in refining their objectives, small groups, independent tasks, and routines/rituals. Specialists may find the tool instrumental in pinpointing specific junctures within a lesson where they can offer constructive feedback and suggest precise accommodations or modifications. Lastly, teacher preparation programs can integrate this tool as a valuable resource for collaborative lesson planning, aiding in the development of teachers who are adept at crafting lessons that foster both academic growth and social-emotional learning.

This lesson plan approach departs from the notion of a classroom that is unidirectionally reflexive only toward its students and attempts to view the classroom as mutually responsive between students and teachers. It is an attempt to leverage research into motivation, sociocultural theory, and self-determination theory elements to build vibrantly collaborative classrooms, intrinsically motivated students and teachers, and authentically developed pedagogical skills. At the same time, there was a constantly maintained concern to ensure that the tools and techniques remain practical, efficient, and that they enhance, rather than supplant, planning and reflection practices. The approach was also used for analytical work for lessons that “went off the rails” and for different teachers having issues with a particular section of students. The materials have even been adapted for use with the school’s social worker and an individual student for behavior discussions as a replacement for traditional Behavior Improvement Plans (BIPs). The work, while nascent, has the potential to impact models for teacher development, mentorship, coaching, and evaluation in addition to the improvements to how teachers plan, deliver, and reflect on their instruction.

Appendix A

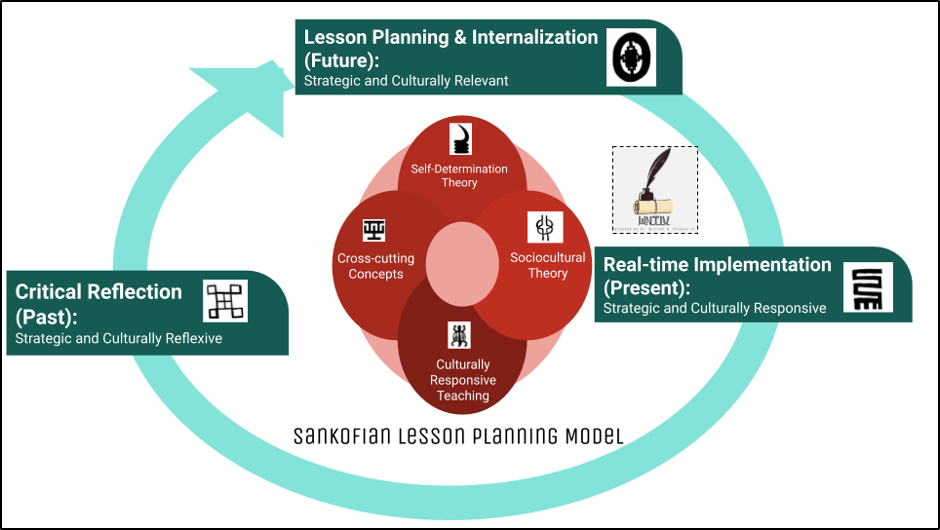

Sankofian Lesson Planning Model

Appendix B

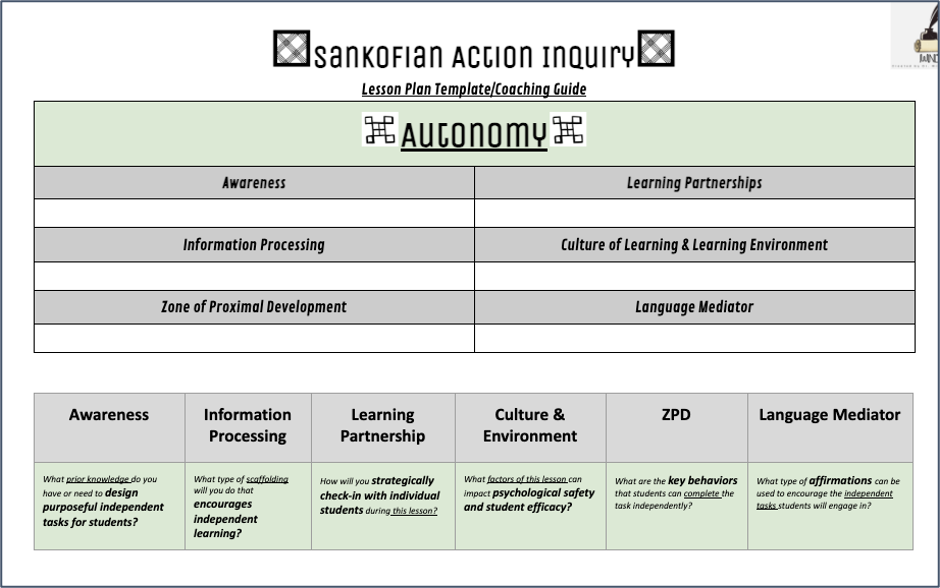

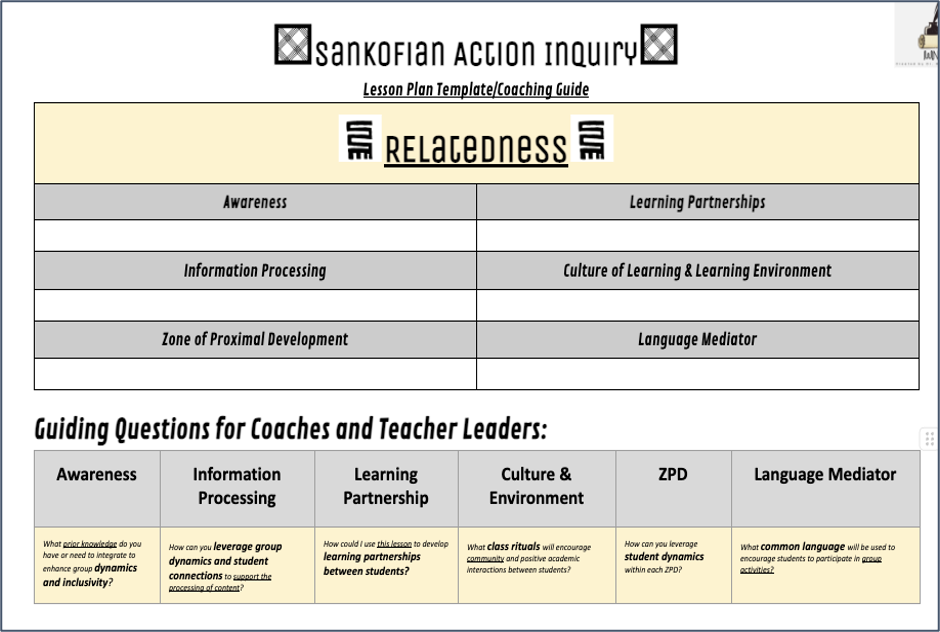

Sankofian Lesson Planning Templates

Hammond, Z. L. (2014). Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students (1st ed.). Corwin.

Harland, T. (2003). Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and Problem-based Learning: Linking a theoretical concept with practice through action research. Teaching in Higher Education, 8(2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251032000052483

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. In Guilford Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2022). An Archaeology of Self for Our Times: Another Talk to Teachers. English Journal, High School Edition; Urbana, 111(5), 21618895. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/archaeology-self-our-times-another-talk-teachers/docview/2665659222/se-2?accountid=8285

Small, P. F., Barker, M. J., & Gasman, M. (2020). Sankofa: African American Perspectives on Race and Culture in US Doctoral Education. State University of New York Press.

Thomas IV, W. (2023, April 18). Discovering Motivational Awareness with African Epistemology. Medium. https://glyphgraf.medium.com/discovering-motivational-awareness-with-african-epistemology-b2f533fa0f4a

Willis, W. B. (1998). The Adinkra Dictionary: A Visual Primer on the Language of Adinkra.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 145.75 KB | |

| 134.42 KB | |

| 155.44 KB | |

| 304.76 KB | |

| 145.7 KB | |

| 164.98 KB | |

| 147.66 KB |