Flux Pedagogy for Equitable and Humanizing Education

The following is a lightly edited/updated reprint of Ravitch, S. M. (2020). Special Twin Pandemic Issue: New Tools for a New House: Transformations for Justice and Peace in and beyond COVID-19. Perspectives on Urban Education. 18(1).

“Everything is in a state of flux, including the status quo.” Robert Byrne

In this moment, life feels like it is in a recovery phase from what seemed like an indefinite state of radical flux. Students continue to feel concerned about their families and communities. Their lives continue to feel disrupted in ways that affect their lives. Many have had to move, some are still in interim housing; others are unable to return to their states or countries given travel restrictions. Students still have unprecedented concerns about their academic lives and career trajectories—what will happen next? How will the realities of today affect them tomorrow?

These are embodied concerns in a time of radical flux—global displacement, people looking for jobs, juggling employment and family responsibilities, worried about and responsible for their health, family health, and public health. The lines between well and sick, healthy and unhealthy have become blurred, as have other newly irrelevant binaries like safe and unsafe, productive and unproductive, distancing and connection. A time of great relational and educational uncertainty, upheaval, and reverberation produced a visibility for the dire need for a more humanizing education system and culturally responsive pedagogical and curricular approach.

Flux Pedagogy

“'Pure experience' is the name I gave to the immediate flux of life which furnishes the material to our later reflection with its conceptual categories.” William James

Flux pedagogy refers to the integration of relational and critical pedagogy frameworks into a transformative and responsive teaching approach. It is constructivist, student-centered, relational, adaptive, and reflexive; it’s a humanizing pedagogy that can help educators to examine the goals and processes of schooling in this moment of extreme uncertainty with a goal of fomenting mutual, collective, durable individual and societal growth, learning, and transformation. Given that the main purposes of our courses have shifted seemingly overnight—from specialized teaching and learning to more broadly solutionary and connective in both humanitarian and pedagogical ways—we must shift as well. Flux pedagogy supports an inquiry-based, emergent design teaching mindset that is adaptive, generative, and compassionate; it is a framework for balancing radical compassion for students (and self) with high-yet-humanely-calibrated expectations for their learning in our courses. This crisis moment requires us to learn new skills and mindsets for designing and enacting relational and transformative pedagogies with our students even as we teach them specific content areas.

Flux pedagogy integrates critical relational frameworks into a complex adaptive pedagogical approach that identifies and addresses lived problems as a form of radical learning towards informed action, particularly through the use of participatory approaches and critical pedagogy practices such as racial literacy storytelling, communal re-storying, counter-storytelling, and critical dialogic engagement peer inquiry groups. Developing your class as a community of practice that supports students in identifying, naming, and pushing against real-time inequities can be the beginning of an emergent critical literacy of educational transformation—an enactment of Appiah’s (2006) concept of cosmopolitanism as a literacy of human connection, agency, and interdependence—a universality of concern for all people coupled with the belief that people are entitled to live into their priorities and ideals without the imposition of what others would choose for them. Further, we can use global, national, and local struggles—and the disparities so vivid across them—as texts of critical inclusivity that support humanistic and equitable schooling, teaching, learning, leading, policy-making, and professional development design and facilitation (Pak & Ravitch, 2021).

The primary dimensions of flux pedagogy are:

- Inquiry Stance Pedagogy

- Trauma-Informed/Healing-Centered Pedagogy Radical

Compassion/Self-care/Self-Love - Emergent Design, Student-Centered, Active Pedagogy

- Critical Pedagogy and Storytelling

- Racial Literacy Pedagogy

- Brave Space Pedagogy

In this piece, I discuss each dimension and offer their integration—flux pedagogy—as a generative heuristic for equitable, responsive, ethical pedagogies. I offer strategies for enacting flux pedagogy with students and colleagues in ways that support the co-construction of courses as brave space communities of practice in a moment where people need more of these affirming and generative professional spaces (Arao & Clemens, 2013; Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Importantly, these theories are not new. Each dimension of flux pedagogy is an existing framework proven generative to theory, research, policy, and practices that support equitable schooling and education. In their integration they constitute a responsive, equity-centered pedagogical framework useful in times of global, national, state, and local precarity.

As an integrative framework, flux pedagogy helps educators identify and examine the hidden curriculum of schooling, including harmful social constructions, impositions of hegemony, and structural impacts on education (Ravitch & Carl, 2019) through collectively reckoning with multiple perspectives on personal, communal, familial, and intra-psychic experiences both before and during this crisis. In my work with superintendents, principals, heads of school, teachers, school counselors, school staff, and students, I’ve found that the flux pedagogy framework enables the co-creation of a third space in which educators and students can take a reflexive step back and support new kinds of relationality that engender creativity, thought partnership and hybridization, active compassion, care, and connection in teaching and learning (Bhabha, 2004).

Inquiry Stance Pedagogy

“For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, individuals cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.”

Paulo Freire

Now more than ever, it is vital that educators situate ourselves as learners, examine ourselves, and study professional practices through a reflexive lens. This excavation helps us to engage, understand, and relate with others through a disciplined and curious humility. Inquiry stance pedagogy is a foundational mindset in flux pedagogy. It requires that educators take a reflexive learning stance on ourselves, our professional practice, and the contexts—near and far, personal and societal—that shape our practice, the contexts of our practice, and our understandings of that practice in and beyond its immediate contexts. Through engaging in intentional, societally contextualized self-reflection, we open up possibilities for more authentic dialogue and critical dialogic engagement, and, therefore, deeper learning (Ravitch & Carl, 2019). Inquiry stance pedagogy creates the necessary education mindset and relational ecosystem for flux pedagogy.

In inquiry stance pedagogy, practitioners situate themselves and students as “legitimate knowers and knowledge generators, not just implementers of others’ knowledge” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009, p. 18). When done with fidelity, this upsets traditional paradigms of what constitutes valid knowledge and who is a valid knower. Further, newer iterations of the inquiry stance framework question why knowledge is even valued over feelings, beliefs, values, and ways of being, thus exposing the invisible-yet-pervasive imposition of these Western constructions of reality and what matters. Identifying these hegemonic frames and naming how they shape lived realities happens best through critical dialogical engagement that focuses on constructively critical engagement and feedback (Ravitch & Carl, 2020). In these vulnerable times, inquiry stance pedagogy invites criticality in how we lead and engage in learning. It helps us to be as resonant, responsive, and mooring for our students (and ourselves) as we can possibly be right now. This requires interrogating circulations of power and hegemonic valuations of proscribed forms of social, cultural, and educational capital.

Inquiry stance pedagogy makes current, typically dominant educational and social arrangements problematic, it: 1) Rejects the dualistic divide between formal knowledge and practical knowledge and shifts focus to local knowledge in global contexts; 2) Positions practice as the interplay of teaching, learning, and leading, as well as an expanded view of who counts as a practitioner and what constitutes practice; 3) Views practitioner communities as the primary medium for enacting inquiry-as-stance as a theory of action; 4) Positions education as a generator of a more equitable and democratic society (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009).

These are evergreen values. Prioritizing relational authenticity through pushing into established hierarchies, prioritizing and deferring to a range of local knowledges, and engaging multiple perspectives and funds of knowledge (González et al., 2005) within an ethic of interdependent care is necessary for student well-being. An inquiry stance foments generative relational learning possibilities instead of sustaining useless (and even harmful at times) hierarchies that counter student success, well-being, and positive schooling experiences. By situating ourselves as active co-learners, we disrupt the expert-learner binary that confers dominance on a narrow knowledge hierarchy and marginalizes the voices and experiences of people and groups farthest from dominant power. In doing so, we create possibilities for dialectics of mutual growth and reciprocal transformation with students in and beyond the classroom (Nakkula & Ravitch 1998).

Suggested Practices

- Situate yourself as a learner broadly and as a learner of community of practice building specifically. Introduce and regularly communicate your learner stance by sharing power with students with the expressed goal of deepening their learning. This can be modeled in many ways including using phrases such as, “I don’t know,” “thank you for teaching me that,” and “we are all learners here.”

- Listen carefully to each student to understand the macro and micro sociopolitical forces present in their educational and life experiences. This means inquiring into and discussing issues of structural inequity and intersectional identities (Crenshaw, 2020) as they are embodied and playing out right now in the lives and educational experiences of our students and their families and communities.

- Consider your own communication style to gain deeper insights into how others perceive you. Remember that understanding has less to do with what is said or intended as it does in how the messaging is perceived, which is mediated by culture and context so eschew defensiveness and invite authentic and critical dialogue with students.

- Be aware of and sensitive to student distress and possible mental health issues as well as to heightened alienation that students may feel related to the imposter syndrome, which can be exacerbated in moments of stress and anxiety. Think about how this time of intensified pressure is playing out in your own life right now and use those insights to build a working compassion and set of intentional support strategies for your students.

Trauma-Informed/ Healing-Centered Pedagogy

“My lifetime listens to yours.” Muriel Rukeyser

In this moment of collective trauma—our trauma, others’ trauma, and vicarious trauma—educators must be attuned to our students’ trauma (past and present) as the necessary first step to co-creating affirming online communities of practice. Trauma-informed pedagogy foregrounds understanding trauma—personal, communal, and inter-generational—and its social and emotional reverberations. It understands trauma awareness and assets-based reframing as central to cultivating a learning environment that is comfortable and affirming to those who have experienced trauma, and recognizing the resilience and resources of individuals and communities who have experienced/ are experiencing trauma (Pak & Ravitch, 2021). Healing-centered pedagogy (Ginwright, 2018) critiques the racialized nature of normative trauma-informed approaches and offers culturally responsive approaches to engaging trauma and engendering posttraumatic growth.

Students need a place to name and process their stress in community—to be seen, heard, and validated, to see that they matter, and to feel connected while the world feels so fraught and coarse. Attention to this aspect of student development is a necessary foundation for all other kinds of learning right now. It is important, for example, to greet each student by name as they come into your classroom, begin each class with warm check-ins, and discuss the importance of each person engaging authentically as a form of community-building and self-care.

Trauma-informed/ healing-centered pedagogy foregrounds the affective dimensions of teaching and considers trauma histories as they play out in learning situations. It is vital to understand that while our students are all traumatized, all traumas are not the same and do not necessarily land in similar ways. While the pandemic is a shared trauma, it lands into the lives of already-vulnerable populations (including some of our students and their families and communities) in ways that cause more severe diffusion effects. As well, some students have trauma histories that must be considered in relation to current challenges and stressors.

As educators, we must educate ourselves and build the skills to identify possible signs of trauma and to connect with our students to make sure they have access to support systems. It is important to be intentional in our language choices when discussing topics that might trigger past trauma. As educators, we must learn create the conditions for student psychological safety and take up an actively supportive role with our students as individuals and as a learning community.

Radical Compassion, Radical Self-Care, Radical Self-Love

Radical compassion, which is the foundation of trauma-informed pedagogy, is the internal imperative to understand reality to change it to alleviate the distress, pain, and suffering of others. Radical compassion actively views suffering within its macro -sociopolitical and -economic realities in ways that are equity-oriented, affirming, and liberatory (Lampert, 2003). Radical compassion stems from staunch criticism of U.S. schools as places that create, exacerbate, deny, and neglect student distress and struggle rather than being in places that help students achieve optimal development by supporting their struggles, resources, and needs as a mission mode. When enacted as a pedagogical stance, radical compassion helps educators feel and build connections between ourselves and our students. Through this, we can see and invent new possibilities for mutual growth and reciprocal transformation (Nakkula & Ravitch, 1998).

Radical self-care is the practice of radical compassion for and empathic kindness towards self. Practicing self-care has never felt more urgent than in these socially, politically, economically, medically, environmentally, and spiritually troubling times. It has become part of many people’s lexicon, yet few consider its deeper vicissitudes, its relationship to social identities and issues of structural discrimination, and the promise it holds for transformative education that can support optimal human development. Fewer yet consider self-care as political. Radical self-care requires examination of social and political power and systems of dominance, grand societal narratives of deficit and privilege imbuement, and the cultivation of a growth mindset built on an examination of how the personal is political and how structural racism and discrimination shape people’s daily lives before, during, and as we live into the aftermath of COVID-19.

Radical self-care transcends material pleasantries to focus on cultivating narratives and routines that help us to lovingly revise parts of ourselves as a necessary dimension of our work to re-envision and reconstruct the world. Audre Lorde (1988) made visible—through her ground-breaking activism, essays, poetry, and thought leadership—how standing in her power, speaking truth to power, and taking joyful care of her body and soul as a Black woman were acts of powerful resistance, radical healing, and self- and societal transformation.

Lorde shared with the world the idea that, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare” (p. 77). Self-love, as critical Black feminists foretold, requires active resistance to internalized oppression and deficitization in a racist and capitalist society.

Adrienne Maree Brown (2017) positions radical self-care as an emergent strategy for living in relationally generative, ecological, and authentically ethical ways that co-create the conditions to foment and sustain personal and collective resonance, healing, agentic interdependence, and self- and societal transformation. Brown grows the concept that “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion” (p. 4) by building and inviting culturally responsive growth axiologies and strategies. These are roadmaps for personal growth, relational healing, and societal transformation that we need right now—we are so blessed to have such meteoric luminaries light our way. So now we must build.

Through advancing discussions of radical self-care and radical self-love and engaging in them ourselves, we can help students develop identity-related stress-navigation skills. These skills include racial and crisis literacies, radical compassion and radical accountability, and authentic communication techniques for critical dialogic engagement inquiry groups that can help sustain them in such complex and trying times.

Across these processes, we must learn for ourselves and teach our students that, as Holocaust-surviving social psychologist Viktor Frankl wrote, there can be a space of transcendent power within oneself even amidst suffering and powerlessness, a way that we can create safe inner lives even from within unsafe external realities, “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom” (p. 18). We can learn and then teach the skills needed to create spaces in which we give ourselves permission to learn how to engage in calm and non-judgmental curiosity towards ourselves and the ways we make meaning of, and react to, people and situations. In doing so, we can create an inner third space, an internal ecosystem of intentional spaciousness in which we can find and build healthy and authentic coping mechanisms that support us and the people around us (Bhabha, 2004).

Once we practice these skills, we can help our students to find and build the strategies and skills that work for them. A question my colleague Dr. Michael Nakkula recently asked in a professional development session we co-facilitated is “Is there healthy stress during COVID?”

And indeed, there is—the kind of healthy stress that mobilizes and motivates so many of us to enact personal, social, familial, and, broadly, educational activism, support, and change in these needful times. We can—for and within ourselves—create a reliable space for observing and non-judgmentally evaluating whether our stress is the healthy kind that motivates us or the unhealthy kind that immobilizes us. We can build—and help our students to build—the agency and ethic of self-care needed to enact this internal system of self-trust cultivation, inner conflict resolution, compassion for self, and radical self-care (Ravitch, 2020).

What’s “radical” about this enactment of compassion and self-care is its unwavering focus on equity and social identity, on the intersection of critical understanding, compassion, and accountability (in a non-Westernized transactional sense of that term) to self and those who deserve it. To discuss self-care in ways that neglect to foreground and complicate social identity and positionality as lived dimensions of structural hegemony further undermines efforts for equity. It also serves to create false privilege and moral equivalents which abnegates the role of structural racism and gaslights people of color, people with disabilities, and other marginalized populations by acting as if they can herbal tea and face mask their way out of the structural conditions that place undue stress, suffering, inter-generational opportunity costs, and disease burden on them as individuals and as demographic groups.

In the news every day, we see how the pre-existing, chronic, systemic racism of our healthcare system already-in-motion creates a diffusion effect of oppressive and inhumane conditions. Radical self-care can help people feel calm and safe within themselves while the world around them feels (and often is) unsafe. This includes identity and emotion affirmation, psychological structures of support, and cultivating bespoke strategies to identify and manage stress and anxiety. While this looks different across people, places, and time, it’s important that radical self-care identify, name, and compassionately attends to the ways that external, systemic pressures, structures, and constraints—in their presence and absence—shape everyday life as well as our narratives of self (Ravitch, 2020, forthcoming).

An approach to radical self-care is communal re-storying, which helps to shift normativizing myths and socially constructed scripts that keep people locked into patterns not made for their actual success and well-being. Generations, for example, have followed the concept of normal—which is a mythology steeped in white male heterosexual upper-class ableism—to exclude, pathologize, and minoritize individuals and groups who “deviate” from the white dominant set of assumptions, values, and frames. Frames that invisibly undergird all facets of society. Given the enduring educational history of the U.S., which is steeped in eugenics, racism, and settler colonialism, it is time to do away with deficitizing impositions of “normal” altogether by supplanting reductive and hegemonic narratives with complex and layered stories of our own and each other’s diversity, uniqueness, multiplicity, and complexity (Annamma, et al., 2013). No one is normal, and there will be no so-called new normal. Let’s jettison this hegemonic language as a form of compassion and care for ourselves and each other, and choose language and ideas that help us re-story and rehumanize ourselves and each other as we live into an interdependent future (Valencia, 2010).

Communal re-storying is a group-healing process that enables people to identify, reckon with, reframe, and move beyond the often-unrealistic and harmful myths and societal scripts that shape our sense of self, hopes, and life choices. Re-storying is a strategy that helps people learn to review and re-index past experiences and conceptualizations of self that no longer serve us well (and perhaps never did). Learning to reframe oneself, to re-index formative experiences that shape our self-narratives in ways that foreground how the personal is and has always been political, is a powerful approach to building an authentic sense of self that can rely on healthy thinking, mental models, and choice-making (Ravitch & Garrett, 2021).

Importantly, communal re-storying helps people cultivate our authentic stories, to hear our inner voices that have often, we learn in airing and talking them out in community, been ignored (even by us) because they were buried underneath internalized social scripts. Communal re-storying helps us to help ourselves and each other build counter-narratives to the grand narratives of deficit that people often turn on ourselves, and to cultivate inner voices that become increasingly liberated from harmful social constructions and cognitive distortions that can some to rule our inner lives and corrode healthy relationships (including with ourselves) if not identified, explored, and thoughtfully addressed (Ravitch, 2020). Radical self-care is the process of envisioning and enacting our bespoke-yet-relational paths forward into a healthier, less burdened, and more agentic and clear vision and version of self in/and the world.

An empathic and responsive approach to our classes, each student, and our collective situation is essential right now; it is a form of radical compassion and radical self-care as well as a humanizing pedagogy. For example, Brandon Bayne, Associate Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, shares these revisions to this semester’s syllabus:

No one signed up for this.

Not for the sickness, not for the social distancing, not for the sudden end of our collective lives and collaboration together on campus.

Not for an online class, not for teaching remotely, not for learning from home, not for learning new technologies under duress, not for limited access to learning materials.

The humane option is the best option.

We will prioritize kindness and supporting each other as humans.

We will prioritize simple solutions that make sense for the most.

We will prioritize sharing resources and communicating clearly.

Don’t try to do the same thing online.

Some assignments are no longer possible.

Some expectations are no longer reasonable.

Some objectives are no longer valuable.

Foster intellectual nourishment, social connection, and personal accommodation.

Accessible asynchronous content for diverse access, time zones, and contexts.

Optional synchronous discussion to learn together and combat isolation.

Remain flexible and adjust to the situation.

No one knows where this is going and what we’ll need to adapt.

Everyone needs support and understanding in this unprecedented moment.

Suggested Practices

- Notice students’ body language, eye contact (or lack thereof), and general state of engagement. Check for signs of wellness, self-care, anxiety, withdrawal. Check in.

- Send brief, open-ended questionnaires or writing prompts asking students to prioritize their most pressing questions, needs, ideas, concerns, etc. Follow up with individual students. This can be repeated as often as makes sense without burdening students.

- Start classes with “free-writes”—give students a prompt and a few minutes to write stream-of-consciousness. Ask students to share a few lines of their writings with the group as a way to shape and ground conversation about potentially difficult topics.

- Familiarize yourself with trauma-informed/healing-centered pedagogy so that you understand trauma more complexly including how it may be present and play out in learning environments through an assets-based lens.

- Attune yourself to trauma—your own trauma, students’ trauma, and the vicarious trauma some students face in their community-based research or practice in schools.

- Create a personal and/or a professional group focused on radical compassion and self-care. Meet often to support each other. Write and share self-care plans. One focus of discussions can be storytelling around timely themes and experiences.

Emergent Design, Student-Centered, Active Pedagogy

“Existence is no more than the precarious attainment of relevance in an intensely mobile flux of past, present, and future.” Susan Sontag

Learning happens best when it is active, responsive, and contextualized. In this moment of global, institutional, and personal flux-induced stress, educators, those privileged enough to take a pause must so that others may soon follow. In this space, we consider the ways this elongated crisis lands into each student’s life, how it lands differently given status and finances, whether or not students have family and community supports, on students unique coping mechanisms formed from past experiences that may or may not serve them well in the present moment. We must focus on our students so that we can help them to face their realities calmly and with a sense of structure, agency, and support. It is vital that we create a seamless, calm, and engaging learning environment for and with our students. Making sure we save energy for our students and that we are caring and positive (and real) when we are with them is vital to their sense of safety and belonging.

Learning experiences must approach emotional well-being as central. This centrality helps students traverse complex systems and chaos, while building relational trust, and locate pedagogical flexibility as an ethical stance. In this stance, everyone’s knowledges and insights are actively valued and called into play, which shakes hierarchical norms to become more of a learning collective in a time of chaos and shared vulnerability. This applies to changes in assignments, responsibilities, and presentations assigned prior to the pandemic. For the social-emotional health and well-being of our students, we need to actively consider their levels of stress as we plan each class, send each communication about changes in the syllabus, lesson plan, or assignment. Specifically, we must be aware of how a student’s situation, as it changes over time, may influence their ability to engage or collaborate on group projects. This is about flexibility as an ethic of practice, being actively student-centered as we work to understand students’ individualized experiences in the context of broader social and political forces so that we actively support them.

Suggested Practices

- Engage in active listening and perspective-taking with intention. Find a thought partner (or two, or a group) to debrief sessions and plan forward.

- Re-envision communication and process norms to push into power asymmetries.

- Ask students what they need as a group. Group discussion of online norms is helpful.

- Discuss reciprocity of efforts and supports within the group to set norms for group work.

- Learning is embodied. Remember to breathe, give breaks, honor physicality even when the class is online. For example, for the first time ever, I now begin classes with a brief breathing exercise given visibly high levels of student stress and anxiety.

- Actively consider students with learning differences and disabilities. Be sure to do your ethical due diligence and not put all of the accommodating on students. Part of this means not requiring students with disabilities or students who need accommodations more broadly to go through the disability office or formal request processes. This is an unnecessary logistical hurdle that you can easily and proactively help them to avoid.

- Provide structure amidst chaos. Abide by start and end times, share a clear agenda, set up rooms and other formats for collaborative learning ahead of time. It’s your responsibility to get the technical support you need so that you can facilitate class with ease. Don’t ask students to take on these responsibilities.

- Re-assess assignments. Ask: What is the most responsive way to achieve equally valuable learning outcomes given current challenges students face?

- Re-calibrate the structure of sessions. Discuss: Talk with students (and colleagues) about new ideas, watch videos of different teaching approaches, re-imagine new ways of teaching (e.g., break-out rooms, using chat and screen share functions strategically).

- Re-imagine assessment. Ask students (and colleagues): What bespoke evaluation frameworks make sense in this moment? One approach is to examine the lesson plan or syllabus with students as an artifact of a pre-pandemic mindset and chart what’s shifted and what the implications are for the field and contexts of study.

Critical Pedagogy

“The world as it was, is, or will be, is beyond common sense, beyond natural understanding: it must be taught.” Masood Ashraf Raja

Critical pedagogy situates students as agentic knowers who can investigate, question, and critique the construction of societal and educational norms in relation to their own experiences; it challenges traditional educational practices that serve to reinforce hegemonic ideas such as notions of students as passive recipients for teachers’ knowledge transmission. Critical pedagogy positions students as critical citizens who can act as agents of social change. Cultivating students’ critical consciousness is the process of building education as a practice of freedom (Freire, 1970; 1973). With all that is happening in the world, this stance helps create the conditions for students to cultivate a sense of agency in relation to what many experience as individual and collective helplessness and hopelessness.

Education for critical consciousness refers to the intentional development of critical understandings of social life that enable reflection on social and political contradictions as grounds for taking systematic action to improve living conditions as they become illuminated by emergent understandings (Freire, 1973). As it pertains to teaching and leading during COVID-19, critical consciousness creates openings to cultivate more critical understandings of the arrangements and limitations of our own educational experiences and to transform them as part of social and educational disruption and reinvention (Pak & Ravitch, 2021). This means, I believe, that we need to move quickly and with resolve into our most flexible and humanizing pedagogies, the pedagogies of hope and love (Freire, 1970, 1992; hooks, 1994, 2003), as we work to minimize opportunity costs by supporting abundance in critical learning and organizational development. This is the heart of critical pedagogy, and it’s vital to engage with our students as active meaning and change-makers.

Re-storying is a form of critical pedagogy, an intentional approach to cultivating intra- and inter-personal awareness and reflexivity within societally contextualizing and affirming contexts. The intentional process of sharing and hearing people’s stories can help us to examine the roots of our ideologies, examine our belief systems, and think more critically about the broader social, cultural, and political spheres that shape them. In these moments of global disorientation, storytelling is a powerful approach to learning, confirming, and contesting reality. It builds and preserves community, while also conveying and affirming a range of knowledges, values, beliefs, and emotions in real-time. Through re-storying, we co-construct the conditions in which we and our students can re-story ourselves with ever-new and more critical insights generated by equity-focused dialogue and reflection (Khalifa, 2018; Pak & Ravitch, 2021).

Suggested Practices

- Start each class with semi-structured storytelling. “Flash storytelling”—strategically timed group storytelling processes, is one way to help a group feel into and across experiences and then relate these to current issues and course topics.

- Help students make connections between course topics and the pandemic through writing and/or sharing personal narratives. Use the participatory approaches of semi-structured storytelling and photovoice (Ravitch & Carl, 2020) to help students relate their experiences of the pandemic to course material. Relate these narratives with narratives from public sources that reflect a wide array of perspectives and experiences.

Racial Literacy Pedagogy

“The lion's story will never be known as long as the hunter is the one to tell it.” West African Proverb

Everyone’s experience is shaped by pre-existing social identities. Don’t assume your experience is similar to your students, or that their experiences are similar to each other. That makes this a good time to engage Dr. Howard Stevenson’s work on racial literacy, which is understood as the ability to read, recast, and resolve racially stressful encounters and identity-related stress (Stevenson, 2014). Right now, it is especially important that educators are well-versed in ways that identity-related stress compounds the trauma of this pandemic, given an understandable lack of trust in our leaders and the system as a whole. It is vitally important that educators rise in these times as representatives of a system that often makes students feel identity-related stress, imposter syndrome, and, even more so than a month ago, at-risk for failure or push out given financial and familial issues that right now are invisible in most education systems because they are not set up for this (but should and can be if properly resourced).

Racial literacy is the ability to read, recast, and resolve racially stressful encounters and consider and address identity-related stress in agentic ways. Reading means decoding racial subtexts, sub-codes, and scripts. Recasting means reducing stress in racially stressful encounters using racial mindfulness. Resolving means negotiating racially stressful encounters toward a healthy conclusion. Racial literacy means that you can read, and thus experience, interaction through an active empowerment framework (Stevenson, 2014). It enables people to see the specific tools and coping strategies they can immediately employ if they find themselves stressed or tense during conversations about identity and equity (and then throughout their everyday lives). It is essential to remember that there are always varying levels of racial literacy and identity-related self-awareness as well as tolerance for tension and disagreement about these realities and issues within our classes (Stevenson, 2014).

There is no panacea for handling the identity-based stress—your own and others’—during conversations about identity and inequity specifically and in everyday life more broadly. Building racial literacy skills through a group process approach facilitates generative discussions (and teaches others to) in ways that contribute to 1) a more authentically engaged milieu, 2) less cognitive dissonance and brave spaces, 3) a sense of community and connection, and 4) preventing or de-escalating tensions or disagreements. Cultivating our racial literacy skills is necessary to be able to support students to do the same. Racial literacy helps educators build and sustain learning cultures that are not afraid to examine issues of inequity, social identity, and racialized stress and that can do so critically, supportively, and productively.

Racial literacy storytelling is a means of learning, confirming reality, preserving community, and conveying knowledge (Khalifa, 2018) that allows educators to “ease into self-reflection and become self-critical without public scrutiny” (Stevenson, 2014). Through identity-based stories, we can reflect on and reexamine what we know, explore and challenge the authenticity of the information we have, reflect on our own actions and their root motivations, and explore the ways that context and history inform patterns of discrimination in the present (Stevenson, 2014). Storytelling is a central tenet of critical race theory, as counter-storytelling serves to cast doubt on the accepted truths told through majoritarian narratives of minoritized communities (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). In this crisis time, wherein social identity directly shapes people’s pandemic experiences. Storytelling becomes a powerful tool for building critical understanding. It helps create the conditions for students to share what’s happening for them, to learn through each other’s experiences, share resources and ideas, and feel less alone. Over time it helps us to more critically understand the impacts of social, cultural, and political forces on our lives and the value of equity dialogue.

Suggested Practices

- Introduce racial literacy storytelling as an approach for practicing how to resolve racialized and identity-related stress and conflict through stories. Create a forum for shared storytelling in relation to identity-related stress. Reflect together on the storytelling process to see if/what it helped individuals and the group develop in terms of 1) self-awareness; 2) inter- and intra-personal insight; 3) relational authenticity, 4) skills for comfort ambiguity and managing discomfort, 5) mindfulness and presence, and 6) empathy, perspective-taking, and compassion.

- Stevenson’s (2014) CLCBE model—Calculate, Locate, Communicate, Breath, and Exhale—is a tremendously useful approach for group (and individual) processing of racialized and identity-related stress. We can think first for ourselves, and then with our students, about the importance of creating new routines and rituals that help us to build a positive relationship with our thoughts and feelings. And further, to learn the mind-body connection by seeing how our emotions live in and speak through our bodies. This is a game-changer for most educators and students (Stevenson, 2014).

- Model and teach racial literacy pedagogy no matter what else you’re teaching. For example, attune yourself to the norm that students of color are often expected to do emotional labor for White people in their classes as well as to the ways that white fragility is imposed onto students (and faculty and leaders) of color, and so on.

- Address inequities and microaggressions as they arise during class (e.g., one student makes an assumption about another student’s situation based on social identity). If you realize this happened after a session ends, be sure to bring it up in the group during the next meeting.

- Work to learn in each class, from each student, where you may be missing the mark. This requires opening yourself up to feedback. For example, share that you’re working on your non-binaried gender language or language to refer to minoritized populations and invite students to offer observations and suggestions.

Brave Space Pedagogy

“If the structure does not permit dialogue the structure must be changed.” Paulo Freire

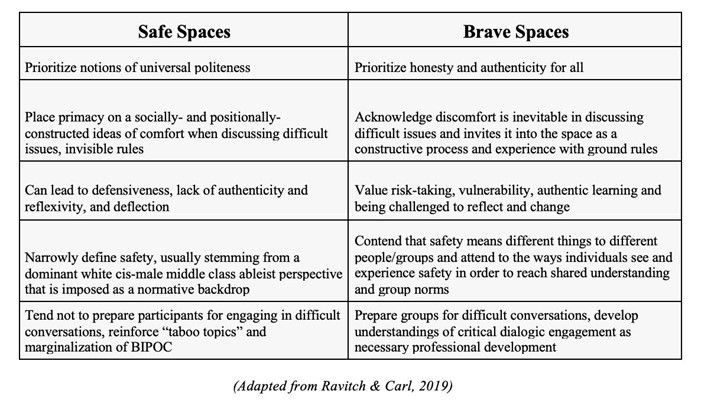

Brave spaces refer to a set of communication and process norms that invite authentic and critical dialogic engagement. When discussing issues that some may find difficult, uncomfortable, or challenging or in which people tightly hold onto strong beliefs, a typical response is to create “safe spaces” for dialogue. The term “safe space” is generally understood to mean a place where everyone feels comfortable enough to speak openly about their opinions and to share their experiences, feelings, ideas, and concerns. However, the concept of a “safe space” is often not

what it seems; what feels safe to one person might feel aggressive, overly polite, inauthentic, disaffirming, or negligent to another. In strong contrast to safe spaces, brave spaces require and create more critically authentic dialogue and the co-construction of equitable norms within groups (Arao & Clemens, 2013). Brave spaces require group bravery. It also requires ongoing leader modeling and engagement so that groups can discuss educational issues in ways that go a layer deeper than what is typically discussed, given that these faux safety rules typically serve to uphold white male middle-class values and norms of communication (Ravitch & Carl, 2019).

Our students’ learning experiences and well-being are our responsibility. It’s vital that we: 1) approach our students’ (and our own) emotional well-being as central to learning; 2) help students to traverse inequitable and complex systems; 3) work to build relational trust with and between students; and 4) view pedagogical flexibility as an ethical stance, wherein everyone’s knowledges and insights are actively called into play in a time of chaos and collective vulnerability. This vulnerability, if we harness it with clarity and vision, can help us to move ourselves and each other into our most resonant, uplifting, and humanizing pedagogies—the pedagogies of hope and love (Freire, 1970; hooks, 1994)—which we need now more than ever to carry us through.

We need to develop our own and our students’ competencies to enact asset-based pedagogies, to foster the conditions for brave spaces rather than safe spaces. Importantly, the very act of exploring the concept of a “brave space” can mark the beginning of a new group dynamic because it acknowledges what anyone who is marginalized in the room already knows: Only people with more social and institutional power (or proximity to that power) get to decide what constitutes appropriate communication (Arao & Clemens, 2013).

Comparing Safe and Brave Spaces

Suggested Practices

- Move away from the inauthentic language and concept of safe spaces, and explicate to students why you are choosing to take a brave space pedagogy stance.

- Introduce Brave Space Pedagogy: Assign “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue around Diversity and Social Justice” and prepare the next session for a participatory process of co-creating inclusive and affirming group norms together (Ravitch & Carl, 2019).

- Prepare to facilitate Brave Space norm-setting. Understand that changing norms requires emotional and cultural intelligence, which require practice through dialogue.

- Foster critical dialogic engagement and authentic collaboration by promoting opportunities for structured collaboration (on and offline) that approach equity and power as central to all conversations, learning, and dynamics (Ravitch & Carl, 2019).

Moving into Flux Pedagogy

Contemplating these emerging global realities, the words of bell hooks (1994) speak to critically hopeful presence in education and offer a way to imagine and build forward:

The academy is not paradise. But learning is a place where paradise can be created…. with all its limitations, [it] remains a location of possibility. In that field of possibility we have the opportunity to labor for freedom, to demand of ourselves and our comrades, an openness of mind and heart that allows us to face reality even as we collectively imagine ways to move beyond boundaries, to transgress. This is education as the practice of freedom (p. 207).

Like hooks, I believe that even with its limitations and constraints, education is a location of immense possibility, which we especially need right now. In these times, the possibility we require lies precisely in finding, creating, and recreating the collective desire and will to view working towards freedom as an opportunity and an ethical imperative. The work of demanding of ourselves, our students, and our colleagues, an openness of mind and heart can help us face the realities of the less-than-ideal society in which we live as we strive to move beyond the borders that confine our lives and our work. While the work of socially transformative education requires considerable focus and energy, our freedom, individual and collective growth, indeed, our survival, is what is at stake.

Annamma, S.A., Boelé, A.L. Moore, B.A., & Klingner, J. (2013). Challenging the ideology of normal in schools, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(12), 1278–1294.

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. W. W. Norton.

Arao, B. & Clemens, K. (2013). From safe spaces to brave spaces: A new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social Justice. In L. M. Landreman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation: Reflections from social justice educators (pp. 135–150). Stylus Publishing.

Ashraf Raja, M., Stringer, H., & Vandexande, Z. (2013). Critical Pedagogy and Global Literature: Wordly teaching. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bhabha, H. K. (2004). The Location of Culture. Routledge.

Brown, A. M. (2017). Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change Shaping Worlds. AK Press.

Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation. Teachers College Press.

Crenshaw, K. (2020). On Intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

Frankl, V. (1946) Trotzdem Ja zum Leben sagen: Ein psychologe erlebt das konzentrationslage. [Man's search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy]. Verlag für Jugend und Volk.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Freire, P. (1973). Education for Critical Consciousness. Seabury Press.

Freire, P. (1992). Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Bloomsbury.

Ginwright, S. (2018). The Future of Healing: Shifting From Trauma-Informed Care to Healing-Centered Engagement. Medium.

González, N., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities and Classrooms. Erlbaum.

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. Routledge.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge.

James, W. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. Henry Holt & Company.

Khalifa, M. (2018). Culturally Responsive School Leadership. Harvard Education Press.

Lampert, K. (2003). Compassionate education: Prolegomena for radical schooling. University Press of America.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lorde, A. (1988). A Burst of Light: Essays by Audre Lorde. Firebrand Books.

Nakkula, M. J. & Ravitch, S. M. (1998). Matters of Interpretation: Reciprocal Transformation in Therapeutic and Developmental Relationships with Youth. Jossey-Bass.

Pak, K. & Ravitch, S. M. (2021). Critical Leadership Praxis for Educational and Social Change. Teachers College Press.

Ravitch, S. M. (2014). The Transformative Power of Taking an Inquiry Stance on Practice: Practitioner Research as Narrative and Counter-Narrative. Perspectives on Urban Education. 11(1), 5-10.

Ravitch, S. M. (2020, March 26). Storytelling, relational inquiry, and truth-listening. Methodspace. https://www.methodspace.com/storytelling-relational-inquiry-and-truth-listening/

Ravitch, S. M. (2020, March 15). The space between stimulus and response: Creating critical research paradises. Methodspace. https://www.methodspace.com/space-between-stimulus-and-response-creating-critical-research-paradises/

Ravitch, S. M. & Garrett, J. M. (2021). Written on the mind: Emotional imagination in Re-storying learner identity and the formation of critical pedagogies. In L. Colket, T. Penny Light, & M. A. Carswell,(Eds.), Sharing our Stories: Exploring the Complexities of Learning and Teaching. DIO Press.

Ravitch, S. M. & Carl, M. N. (2019). Applied Research for Sustainable Change: A Guide for Education Leaders. Harvard Education Press.

Ravitch S. M. & Carl, M. N. (2021). Qualitative Research: Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological. (2nd Ed.). Sage Publications.

Roy, A. (2020, April 3). The Pandemic is a Portal. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

Rukeyser, M. (1968). The Speed of Darkness. Random House.

Solórzano, D. G. & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44.

Sontag, S. (1969). Styles of Radical Will. Picador.

Stevenson, H. C. (2014) Promoting racial literacy in schools: Differences that make a difference. Teachers College Press.

Valencia, R. R. (2010). Dismantling contemporary deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. Routledge.