Beyond Words: Reimagining Education through Art and Activism

The COVID-19 pandemic has once again revealed the urgent need to address ongoing injustices at every level of U.S. society. In this article, we combine visual art, research, and storytelling to discuss the need for such systemic change within schools, specifically focusing on the effects of discrimination against students who speak languages other than English. The authors draw on their own lived experiences, research, and artistic expression to make an argument for turning to creative, arts-based practices and diverse linguistic and cultural representation within classrooms and curriculum. The authors’ reflections and artistic contributions demonstrate the importance of using the arts to validate, embrace, and learn from the fullness of students’ creative, critical, and linguistic repertoire in the fight for justice within and beyond schools.

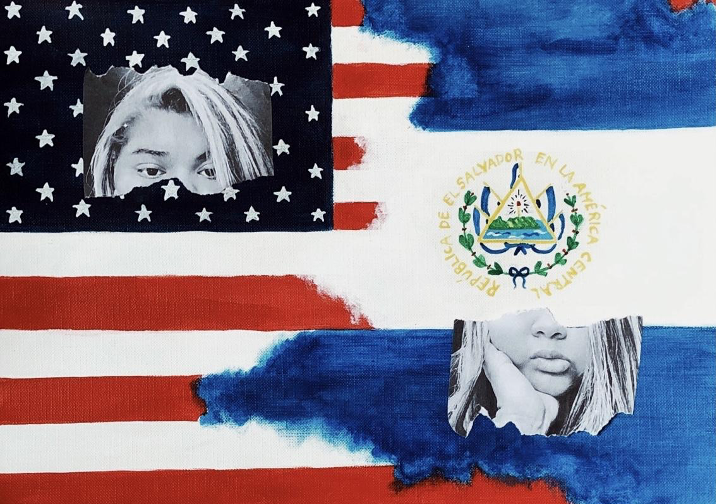

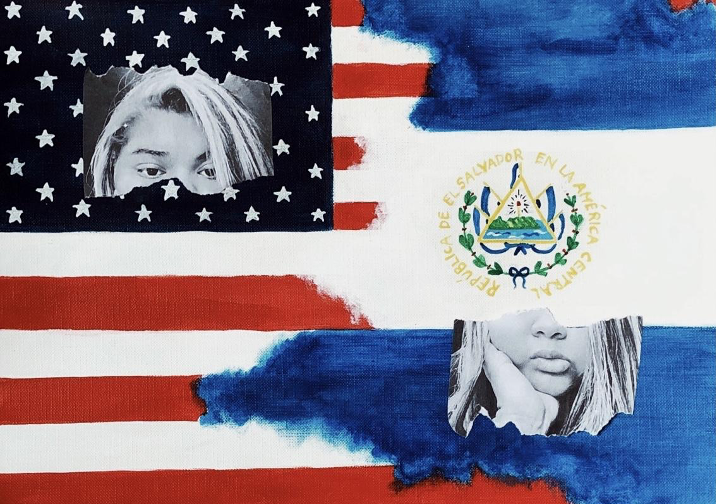

Visual Abstract: This collage previews artwork created by the four authors, which is also integrated throughout the article.

Keywords: the arts, activism, poetry, participatory research, linguistic discrimination, representation, bilingualism, multimodality

In President Barack Obama’s nationally televised commencement address to the high school class of 2020, many of whom graduated from living rooms in the midst of a global pandemic, he said “You don’t have to accept the world as it is. You can make it into the world as it should and could be.” Three of us (Mikaela, Perla, and Joselyn) are among that class of 2020. We are also part of a group of media-makers, artists, and writers currently collaborating (with Bethany) on a variety of arts-based projects, and the four of us are writing this article together to discuss how the arts can contribute to making the world “as it should and could be” – starting in schools.

Obama’s speech illustrates the revived sense of urgency to address the social inequities in health, education, and housing emphasized by the pandemic, all of which are upheld by White1 supremacy and colonization. These structures that establish White dominance across socio-economic systems have threatened minorities’ existence – their very ability to be – and hindered their ability to excel. Obama’s speech also demonstrates how people around the world and from older generations are turning to us (Joselyn, Mikaela, Perla) as the generation who will reverse global warming, protest for what is right, end gun violence, combat police brutality, and create radical change. For all of us (including Bethany), the pandemic has shown both the depth and urgency of these issues and has reminded us that there will never be a better time to act than now. We realize that there is a need for systemic change: one that starts in the classroom. As current and future students and educators, we believe in the power of education to create change. However, we also ask: how can we use education to create change when the educational system itself needs changing?

In this article, we discuss how classrooms are still sometimes places that do not fully acknowledge all students’ humanity and identities. Society often believes that schools provide equitable learning opportunities across age, gender, race, and class. However, based on our own experiences in school systems, we understand that the classroom can also be a place where identities and abilities are hindered and suppressed. Therefore, in this article, we ask: How can we reimagine classrooms and schools as places that cultivate necessary social change by embracing students’ multiple stories, voices, and modes of expression beyond English-centric text-based communication? How can we create schools where multiple languages and forms of expression disrupt problems that permeate educational systems, such as representation across the curriculum and linguistic discrimination?

As artists, media-makers, and poets, we turn to the arts as a possible solution to some of these problems. We have seen the inherent power of art in our own lives, both in and out of schools, and we believe in its ability to teach us more about ourselves and others. Specifically, we ask what role the arts, and – in particular, student-produced art – can play in dismantling the White, Eurocentric, monolingual, monomodal, and hegemonic cultural norms that have been set for decades?

Context and Process

We came together to discuss these ideas through a collaborative media-making group that Bethany formed after we met each other in a college-bridge program. As we learned more about our (Perla’s, Joselyn’s, and Mikaela’s) shared experiences as first-gen, Latinx students transitioning to college, we also learned more about all of our (Perla’s, Joselyn’s, Mikaela’s, and Bethany’s) shared perspectives on the problems and promise of schooling in its current form. Although Bethany is not Latinx or a first-gen student, the four of us all share common commitments to educational equity and the arts, which prompted our decision to collaboratively author this article. The COVID-19 pandemic has exasperated many of the inequities seen within schools and has amplified the need for equity within and beyond them. It is this need that compels us to reimagine what education can (and should) look like through our stories, art, and research presented here. We do not want other students’ potential and right to a good education to be stifled by all of the inequalities within schools. Every student is deserving of the same opportunity to learn, grow, and thrive.

We want this article to serve as a model for the power of collaborative authorship among students, researchers, and educators, so we believe it is important to say a few words about our composing process. Bethany, who is currently a Ph.D. candidate, first received the invitation to contribute to this issue and then invited students from the media-making group to join as co-authors: a call to which Mikaela, Joselyn, and Perla responded. We then met weekly via Zoom to discuss our experiences, previous research, and our goals for the article. Bethany served as note-taker during these conversations, often transcribing statements word for word, and these notes then became the outline and rough draft for our article, to which we also independently added sections, artwork, research, and stories. We worked together in a google doc and shared resources via email and in a group text. Throughout the process, we conducted research using scholarly and publicly available resources, drew on our lived experiences and research we had done in previous classes, wrote together and alone, made and shared art, and edited, commented on, and discussed each other’s work.

At the core of our argument is a belief in making academic writing accessible and welcoming to a wide range of audiences as we try to reimagine what education can look like. In order to mirror this belief, we made an effort to make this article itself useful and accessible by explaining specialized vocabulary, using straightforward language, and avoiding jargon. This is important because radical change can only be created with the help of everyone; therefore, the more people who can access the ideas we present in this article, the more people can comprehend the issues at hand and work toward our proposed solutions. We used a mix of first person plural (we) and singular (I) as a way to honor the fact that we are all sharing authorship as well as personal stories and experiences, and we include our names in parentheses when appropriate to specify which experiences were unique to individual authors. Last but not least, we include artwork that reflects our argument and emphasizes how we use art as a way to understand ourselves, others, and the world around us.

Defining “The Arts”

When we discuss “the arts” in this article, we are talking about using any mode, method, or platform to create and express who we are and how we see ourselves in the world. We define art as a transformative creative expression that provokes empathy and thought, represents internal thoughts and feelings, and is open to multiple interpretations and connections. We want to make it clear that our artwork in this article is limited to our vantage points and to the mediums we use, but the creation of art is not and should not be limited to the usage of traditional mediums (e.g. paintings, sculptures, writing, etc.) but also includes various contemporary mediums (e.g. computer code, collages, and digital media). Thus, in advocating for an expansive vision of schooling and scholarship that includes the arts, we advocate for an expansive definition of “the arts” as well.

Building on the Work of Others

Our advocating for the arts as a means of creating necessary change within schools is based both on our own experiences and our reading of scholarly literature (e.g., Greene, 1995; Albers & Harste, 2007; Gadsden, 2008; Vasudevan, 2016). We have turned, for example, to the work of Whitelaw (2017), who explained how teachers and students can use visual, literary, and other art forms to create “a diverse, humanizing curriculum” (p. 67) where students participate in exploring, shaping, and representing stories about themselves and others. Further, according to Burmaford, Brown, Doherty, and McLaughlin’s (2007) research on art integration, the arts can be used as a mode to help students expand their cognitive and linguistic skills.

For example, Weltsek and Koontz (2018) described how integrating visual, dramatic, and sculptural arts into a English class invited students to exercise critical and creative thinking toward global injustices. In Orellana, Martinez, Lee, and Montaño’s (2012) study, Latinx middle schoolers used filmmaking to recognize, honor, and learn more about how they used English and Spanish in their school, homes, and communities. Flores (2018) wrote about young creative writers who wove Spanish and English together through poetry, demonstrating how poetry can promote awareness of racial injustice and hope in students’ own futures. In de los Ríos’ (2018) study, she shows how students created powerful social media videos that combined image, text, English, and Spanish to highlight police brutality and injustices within the U.S. immigration system.

This brief literature review highlights the arts’ capacity for developing self reflection, cultural awareness, and empathy. It shows how this capacity can be harnessed by schools and used to address problems we have noticed in our own schooling experiences. These studies demonstrate the value of blurring the distinction between fine arts, popular media, and traditional “academic” genres in creating engaging learning experiences that honor students’ identities, languages, and abilities to activate meaningful change.

Honoring our Own Lived Experiences

In addition, we recognize our own lived experiences within schools as valuable sources of information on this topic. We share an understanding that “minoritized identities and communities provide unique and invaluable epistemic vantage points from which to understand our shared world, including how it (re)produces inequality” (Campano, Jacobs, & Ngo, 2015, p. 99), and we have discussed how our epistemic vantage points – our own ways of knowing and understanding the world – uniquely situate us collectively and individually to provide insight on these topics. For this reason, we center our own perspectives in this article because our analytic, linguistic, artistic, and reflective insights can serve as both map and model for a more just, creative, and inclusive educational future. We intertwine visual, poetic, and storytelling arts in this piece, following the lead of Johnson, Gibbs Grey, and Baker-Bell, (2017) who center the storytelling practices of Scholars of Color in order to “put our collective stories in conversation with one another and against dominant narratives and stories that perpetuate White privilege, White supremacy, and patriarchy” (p. 470).

In this article, we offer stories of our own experiences that demonstrate the need for and possibility of reimagining the modalities, languages, and methods of educational research and practice. In sharing these stories, we want to honor the role and validity of passion, emotion, and anger in these conversations, especially when speaking from one's lived experiences – which we do not apologize for – while also acknowledging and promoting the right to protect ourselves, our stories, and our vulnerabilities. We also want to reiterate that we are often speaking from personal experiences and not assuming how others should feel or how they should respond; these are individual, unique experiences and we do not expect everyone else to feel the same way.

Defining a Problem: Devaluing Linguistic Diversity & Students’ Identities

One of the problems we believe it is important to address in the current educational landscape is the issue of linguistic discrimination in schools and in society as a whole, which is connected to the racialization of students and racism within schools (Flores & Rosa, 2015). We agree with Martinez (2017) that “for too long, Black and Latinx youth have been asked to sound like their White counterparts in ways that fail to legitimize and humanize them in our English classrooms” (p. 184). Based on research we have conducted in this area, we know that teachers’ unconscious biases towards students who do not speak the standard English has detrimental effects on students’ educational achievement and emotional development (Callahan, 2005; Callahan, Wilkinson, & Muller, 2010).

As we talked and wrote together about our own experiences in classrooms where languages and variations of language other than what is recognized as “standard” English are scrutinized and penalized, we realized how important it is that various accents, dialects, and languages are validated in the classroom. This validation depends on teachers ensuring multiple languages and dialects are represented in course materials and promoted in students’ discussion, writing, and creative practices. This is not only important for ensuring students’ academic success but also has important civic and social consequences. Many schools center Whiteness by privileging ways of talking and writing associated with Whiteness. As a result, there is a lack of validation and representation of languages and dialects, which “others” students who do not speak standardized English, making them more vulnerable to losing their sense of place and belonging. This also leads students to hesitate to promote changes within their environment. After all, why change aspects of society if you were not welcomed or a part of it to begin with?

My (Joselyn’s) parents immigrated to the United States and the Spanish language was one of the few things they carried along with them, which they passed down to me and my siblings. It wasn't until I entered ESOL in kindergarten when I realized that my Spanish as well as the culture it brought along with it was something I had to put away in a classroom setting. I have a vivid memory of speaking to a girl in Spanish, trying to be friends with her, and a teacher interrupting our conversion to tell me I had to speak English. The same teacher would only encourage my Spanish-speaking whenever another Spanish-speaking student needed translation. In other words, my Spanish was only honored when it was beneficial for the teacher, otherwise my native tongue was not something to be proud of. Despite being in ESOL for six years, I can still feel the intense sense of embarrassment I felt when being taken out of class for ESOL testing. My classmates' piercing eyes as I left the room served as verification in my mind that I was less intelligent than my peers...and they knew it too.

Memories like these left a sour taste in my mouth and formed the foundation for my continuing love/hate relationship with Spanish. It also instilled within me the idea that English – and by that I mean standard English – is the only language of proper education. This false pretense later led me to have academic insecurities in my college-level courses, especially during my senior year of high school. My classmates wrote essays containing elaborate and complex vocabulary that I didn’t understand, which intimidated me. I was, once again, the girl who was taken out of class because she didn’t know English. Despite my passion for English, I sat in class feeling as if I was rejected by one of the subjects I found the most comfort in.

This process of requiring students to assimilate to the norms and standards of language use established by Whiteness is not a new problem and is tied to colonial and racist histories in which children who speak languages other than English are separated from their languages and cultures. For example, during the late 1800s, many Native American children were separated from their families for long periods of time to attend government- or church- run White boarding schools. These boarding schools were created for the purpose of completely stripping Native American people of their culture and language in order to assimilate them into the hegemonic Eurocentric culture. Upon attending, they were forced to cut their hair, to never speak their Native tongue, to replace their religions with Christinaity, and to internalize hate for their culture (National Museum of the American Indian). At the core of these schools was a mission to dehumanize, which is echoed in the statement by Captain Richard Henry Pratt who founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School: “kill the Indian and save the man” (Official Report of the Nineteenth Annual Conference of Charities and Correction).

Looking at my (Mikaela’s) own experiences of assimilating, like many others’, it did not really feel like a choice. When I came to the United States I felt a pressure to learn English quickly, which on its own was not bad since I was eager to understand what the other English speaking 2nd graders were saying. I recall a moment when a girl in my 2nd grade class called me stupid for being unable to understand what the teacher was saying and being unable to properly answer the question in English. It hurt me to feel like an outsider for not speaking English and subsequently having separate classes to learn English (ESL). I am not mad at that girl because she was too young to know any better. However, this speaks to a larger misconception that ESL and language acquisition is directly correlated to your level of intelligence or lack thereof. It was that association that urged me to learn English quickly, get rid of my accent, and try to get out of ESL as quickly as possible. Today, I get the occasional “oh wow, you don’t have an accent” or “you speak very well” when I tell people I am from Bolivia and I immigrated here when I was seven-turning-eight years old. Although these statements are well-intentioned, they are inherently harmful because they are congratulating me for successfully assimilating while at the same putting down others who have not met those expectations. Sometimes, these statements remind me that I am an accomplice in losing pieces of myself, especially when I have assimilated my own name to sound “American,” because I thought that made it easier for everyone and was a prerequisite for moving into a new place that at first did not feel like my own. It has been a long process of unlearning and relearning, and each day I try to make small steps into getting rid of internalized hate. The biggest first step that I have tried to do is to introduce myself with the correct pronunciation of my name and correct those who mispronounce it. It is very hard and sometimes I forget to do it, but it is necessary.

I (Bethany) was somewhat aware of how students like Mikaela, Perla, and Joselyn experienced linguistic discrimination during my time as an ESL teacher, but the scale and impact of this discrimination was brought into sharper relief during a conversation I had with a student while teaching English in Turkey. As someone who grew up as a monolingual English speaker, I was eager to learn and practice another language while living and teaching abroad, which was an opportunity I had access to through my status as a U.S. citizen and so-called “native” speaker of English. During breaks between classes, I would often practice Turkish phrases with some of my students, and one day a student asked me to please use English when chatting with them, explaining: “Teacher, you want to speak Turkish, but we need to speak English.” This phrase has stuck with me ever since. I still try to practice other languages, but with a heightened awareness of the privilege I have of doing so as a hobby, while for many, bilingualism is an economic, social, and educational necessity. This story reminds me that my identity as a White “native” English-speaker affords me power, mobility, and opportunities in a world where Whiteness, U.S citizenship, and the English language are used to disempower and oppress others. My student’s statement that day represents a global imbalance of power that tilts toward English speakers and Whiteness, not only with the U.S. school system, but at a global scale. This story, that student, and the many other students whose stories and identities have been silenced in classrooms that uphold the dominance of Whiteness and English (including my own), motivate me to work toward teaching and research practices that tilt back the scales of linguistic and representative injustice in schools.

Discrimination against Spanglish

One of the forms of language that is often discriminated against is “Spanglish,” which is “a hybrid language combining words and idioms from both Spanish and English, especially Spanish speech that uses many English words and expressions” (Lexico.com). Spanglish also consists of words that do not technically exist in standard Spanish but are commonly used by Spanish/Spanglish speakers. For example, in Spanish, “to park” is estacionar, but in Spanglish it would be parquear. Spanglish serves as a living representation of Spanish-speakers’ method of merging into an English-dominated American culture. Speaking two languages means constantly navigating two worlds and two languages, which is something we (Perla, Joselyn, Mikaela) can relate to when it comes to speaking both English and Spanish fluently. Although Spanglish is commonly spoken, it has its emotional and social consequences due to the stigma around it, which comes from the native speakers of both languages. When talking about Spanglish, the question of: “Should I be Hispanic, or should I be American?” pops up in the conversation (Phillips, 2019).

For me (Perla) there has always been this confusion of whether or not I belong in either culture. Although I grew up with Spanish being the only language I knew, eventually, as I started getting fluent in English, it became a battle of whether I am more Hispanic than American and vice versa. This was especially true when I would go to school and I would see all White people and then compare myself, feeling like I don’t look like them and yet I am one of them. Then, I would come home to Salvadoran culture where only Spanish is understood and you watch the news in Spanish while eating all the traditional Salvadoran foods. I am proud of both of my cultures because being American has given me so many opportunities, but at the same time being Hispanic has given me the gift of being bilingual. When you go to a school where the majority of the population is White you do feel the need to fit in, but at the same time you have something that makes you unique and different from everyone else there, which makes code-switching between school and home a normal practice.

Figure 1. “3,060 Miles Apart” by Perla Gonzalez

Code-switching is the alternating between two or more different languages, which is common in societies where multilingualism is present, similar to what bilingual education scholar Ofelia García often discusses as translanguaging (see García, 2009, García & Levia, 2014). One teacher, Meghann Peace, explains that “Bilingual speakers have to know both languages very, very well in order to code-switch in the same sentence” (Phillips, 2019). It tends to be that “that the strongest bilinguals also tend to be the most prolific code-switchers” (Poplack ctd. in Sayer, 2008, p. 104). Code-switching not only is a normal behavior for students that speak other languages, it leads to them “becoming aware of the rules of politeness and the cooperation principle in social interaction” (Klapicová, 2017, p. 45). So although there might be a stigma attached to Spanglish code-switching and translanguaging, the benefits that children get from using these skills because of their Spanglish is something that can not be taught.

We believe that Spanglish should be just as valid as any other Spanish dialect. Language and meaning have been shaped by culture and context because the two different cultures have been mishmashed into one by the people who live in that reality. Spanglish isn't the only dialect that has formed from contact between two languages — there's also Franglais, Portuñol, etc. Although Spanglish has not been accepted by most native speakers, it should be because there is so much more behind the dialect. Not only does it help us (Joselyn, Mikaela, Perla) express ourselves and connect with each other on a deeper level, it also forms part of our stories and identities.

The Need for More Diverse Representations across School Curriculum

One way of combating the problems of linguistic discrimination in schools is to foster more diverse linguistic, cultural, and expressive representations within school curriculum, altering the definition of who, what languages, and what modes are considered “academic” and valuable in educational settings. Minoritized students who face discrimination in schools may focus more on trying to conform to the norms of society in hopes to gain more acceptance from society (Tatum, 2000). For this and other reasons, many education scholars and teachers have long advocated for including more diverse texts across K–12 curriculum (e.g., Bishop, 1990; Botelho and Rudman, 2009). Having an increase in diverse representations of languages, cultures, and modes of expression within school curriculum will allow students who are not a part of the dominant demographic to feel more included, validating that they are vital members of society. Their voices and concerns do deserve to be heard and taken into consideration when creating an inclusive educational system. More diverse representation will foster an environment that will allow students to be themselves and to develop into their ideal selves rather than what society expects them to be. Therefore, we argue for the inclusion and creation of the arts, not only within the humanities but across the curriculum, as a way to bring more diverse representations of identity, language, culture, and knowledge production into classrooms that have long been filled with English-language, Eurocentric, and prose-dominant texts. Not providing alternative opportunities for expression further centers Whiteness and makes classrooms breeding grounds of inequity, contrary to the very aim of public education.

In my (Joselyn’s) personal experience, due to the lack of representation of my demographic, I started to rely on creating connections with the texts I was given by the curriculum. Within my environment, it’s normal to speak in slang. When I learned that Shakespeare also created and used slang, this allowed me to feel more comfortable with my writing within a standardized English academic setting. Despite this connection, as a recent high school graduate, I wish I saw more demographics being represented other than dead, White guys. At an emotional level, I was able to relate to the common human experiences discussed, but there was a disconnect between identities. I needed to read more about and by authors with minoritized identities. I remember the euphoria I felt reading the novel, I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, by Erika Sánchez during my senior year of high school. It was my first time reading a book written with Spanglish and by a Latinx author. I finally felt represented after twelve years in school.

As students who have graduated from different high schools within Northern Virginia and have been in advanced classes where the majority of students and teachers within the classes were White, we (Perla, Mikaela, Joselyn) have seen how these curriculums lack in diversity. This is especially apparent when it comes to literature in our English classes where usually the novels being read are texts such as Romeo and Juliet, The Catcher in the Rye, and Of Mice and Men, where the authors are White. If the only art we encounter are books about dead, rich White people’s (mostly men’s) experiences, then how can we create broader conceptualizations of humanity? Often, our only experience with diversity in the curriculum was through our Spanish and Art classes. We see this as a problem because not only does a curriculum that lacks in representation throw off students who are in the minority, it also only leaves room for one type of story to dominate the narrative at school. Therefore, when representing only one person’s story, often the discussion is going to be centered around that one story, making us feel as if the writing or artwork of people who look and speak like us (Perla, Mikaela, Joselyn) are not important and leaving us with a sense of “not belonging.”

Incorporating arts into the curriculum as “mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors” (Bishop, 1990) must be done intentionally to create a wide range of representations through which students can better see and understand themselves (in mirrors) and empathize with others (through windows and doors). However, including diverse representations in curriculum does not mean only including stories about the suffering or oppression of minoritized people. When using texts and artwork created by people from diverse backgrounds, it is important to do so in a way that promotes action as well as empathy – to go beyond words and use visual art, music, and literature, as prompts toward intervention in social and civic life. We suggest that teachers use conversations about art that represents a range of perspectives and lived experiences as opportunities to build more acceptance, and to open and mediate conversations about topics that might be stigmatized, avoided, politicized, or uncomfortable.

Powerful Experiences Encountering and Creating Art

We argue for the intentional inclusion of the arts across the curriculum because of the power that the arts have to create the type of change that is needed in the world right now. What we write and create helps us understand our own identities more as well as how we fit into and see the world. We believe in more intentional inclusion of the arts because we have seen ourselves within art, and we have also seen how art can communicate meanings that are private or particular to specific communities.

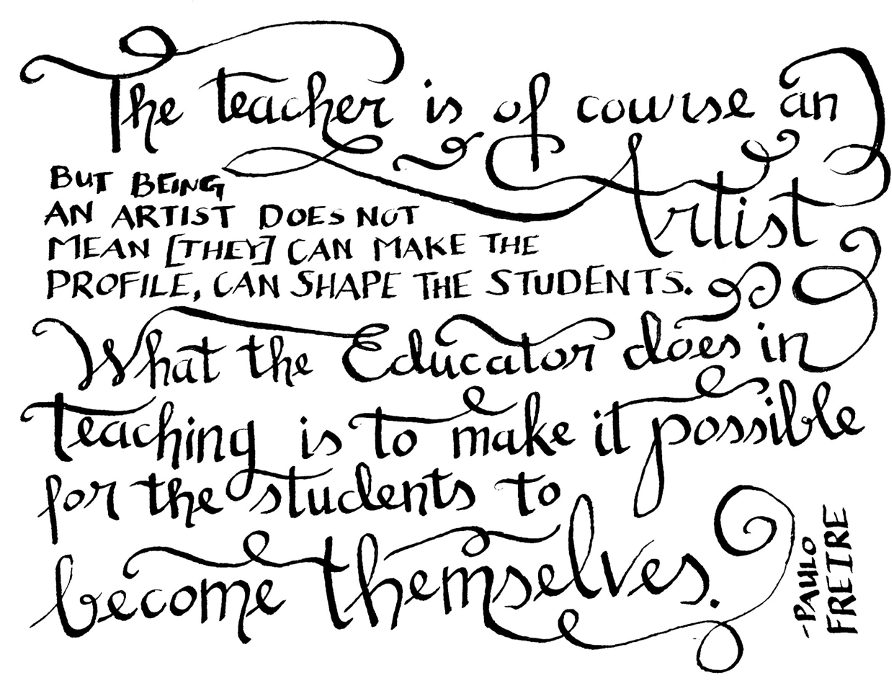

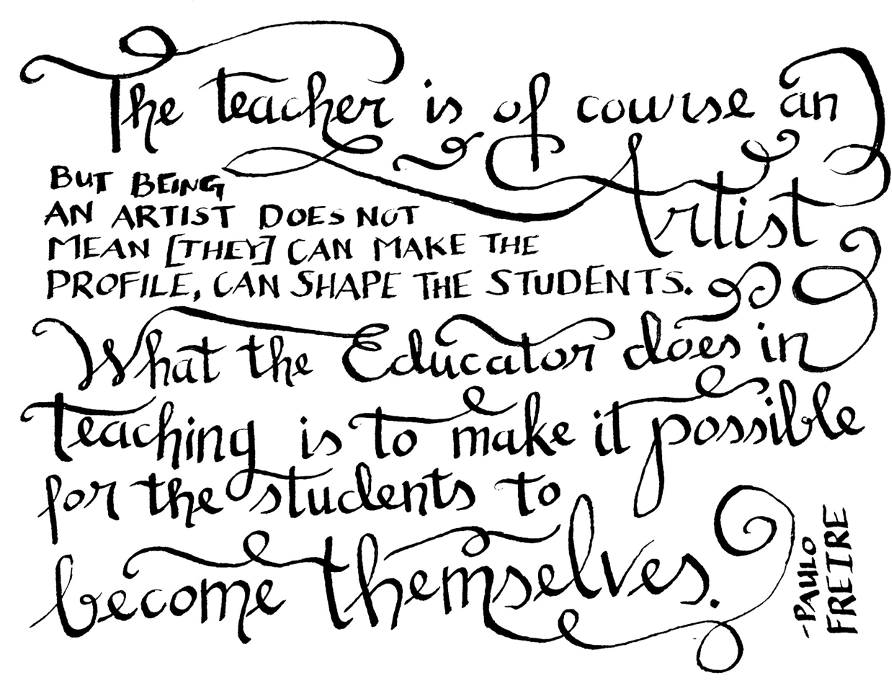

Figure 2. “The teacher is of course an artist” by Bethany Monea

As a teacher and a researcher, I (Bethany) have consistently turned to visual and literary arts to expand my own pedagogical and analytic practices. Creating my own art has been an important part of my professional and personal development; I have often turned to creative writing, graphic arts, and media production to ground me in work that feels joyful and meaningful, and these practices have often helped me reach different types of analytic insight than I could have otherwise. I also turn to the arts as an opening for collaboration and shared knowledge production. Engaging in participatory arts-based research helps me understand my own and students’ experiences of schooling in more multi-dimensional and multimodal ways, and it creates spaces where I can continue to learn from the artistic productions of the students who I ultimately want my academic scholarship to benefit. Working in partnership with scholar-artist students like Mikaela, Joselyn, and Perla on this piece exemplifies how the arts have impacted my own practice as a student, teacher, and researcher.

Figure 3. “Hope” by Mikaela Pozo (click image to zoom)

Art has played a crucial part in my (Mikaela’s) development. Thinking more specifically about my own experiences with art as a mode of expression and self-discovery, I have come to the conclusion that I would have not gotten this far in understanding who I am and what I want to do in life if not for art. In my freetime and throughout my high school years, writing poetry has been one of the few times in my day where I can reflect on how I feel, how I see myself, and how I see the world. It was those moments where I could reflect on my experiences of being a first-generation, Latinx, immigrant, person of color that ultimately urged me to want to fight for racial equity and economic liberation for other people of color. In the classroom, I encountered more of an emphasis on the basics of poetry and even the types of poetry. However, there was not an emphasis on using poetry as a mode of self-discovery and creativity, even though at its very core that is what poetry is. Furthermore, a lot of the poems and literature presented in my classrooms were not reflective of students’ experiences. The first time I truly saw myself reflected in the work of another person was when I heard Elizabeth Acevedo’s spoken word poetry. Her poetry and her books resonated with me, which was something I did not experience often. Her poetry specifically inspired me to keep writing and re-emphasized that this is the way that I want to express myself.

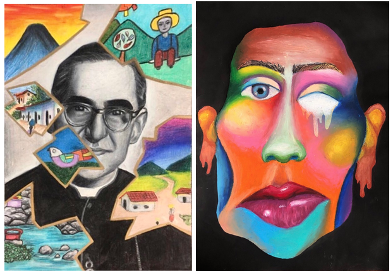

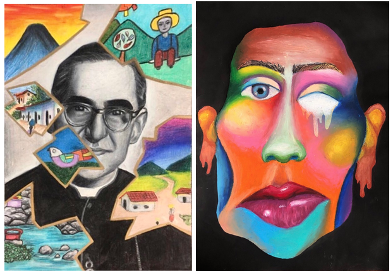

Figure 4. “The Saint” and “Unknown” by Joselyn Andrade

Through this partnership, I (Joselyn) have realized that art has been an influential factor throughout my life. When I was young, my pops introduced me to various musicians. This exposure to a wide variety of music genres showed me at a young age how universal art can be. As a young kid, I was able to not only see my own identities represented in music but also a vast list of others. This representation planted a curiosity within me to discover more about the identities that I was unfamiliar with. Though I did not understand it in its entirety, music served as my first looking glass into other lives and experiences as well as an understanding of my own.

My relationship with art changed as I got older. I no longer wanted to only consume art but now desired to create it as well. Creating art provided a release from the intensities of life. To me, there is no comparable state of peace than creating art during the night. The hypnotic state you enter as you draw liberates you from the imprisonment of worries and doubts. I have silent conversions between the mediums, the canvas, and my truth. As an artist, I can cryptically display personal thoughts to the world without having to truly say much. Art has provided the clarity and the environment needed to see myself in my entirety, as well as the world. It has allowed me to be more connected with my Salvadoran heritage and feel closer to a country whose soil I have never touched. Art will forever serve as a personal guide into understanding myself and common human experiences.

As a student who wants to be a future educator, I (Perla) see the importance of art especially in my life. Not only does art help me relieve some of my stress, it also helps when home and school responsibilities become a bit much. I believe that art has many different forms and can help not only with relieving stress but telling one's personal story and letting others relate to it in their own ways. From my freshman to my sophomore year of high school, I was able to work on what is known as an MYP (Middle Years Program) project where you could choose whatever you wanted your project to be. I decided I would tell a story about myself through artwork. So, I made four different canvases with different images of me or things I did to show my introvertedness and my extrovertedness. With this experience I was not only able to show my talent but I was able to have people learn a bit more about me through a series of artwork and quotes. When having projects other than essays or presentations, I always go the creative way by making art and showing that you do not always need words to get a story across. As for wanting to be a future educator, I have seen methods of teaching that I do not like and that I do like. Based on what I have learned from those experiences I know that I want to show my future students that there are many more ways of telling or interpreting a story than just writing. I want to show them that you can use art to challenge the status-quo and reimagine practices for the better.

Conclusion: Toward Arts and Activism

We want to be clear that we do not see the arts as a panacea that will solve the problems of linguistic, racial, and cultural injustice in and out of schools that have been made all the more urgent by the current pandemic. Because we see schools as a microcosm of culture, we have focused on how arts can remedy some of the problems we’ve noticed within schools. The power of art is its ability to help holistically integrate students’ lives beyond what’s traditionally valued in schools, such as Whiteness and certain forms of the English language. We believe that shifting school cultures can shift broader cultures.

As we reflect on the pressure and responsibility we feel to contribute to creating a more just and equitable world, we also reflect on how overwhelming it can be to find our way to go about making this change. In particular, we (Perla, Joselyn, Mikaela) find ourselves asking, “Will my life align with what is needed from my generation?” Work that meets the standard for our generation will take both innovation and courage, but all four of us recognize that there are many different ways to contribute and make change. Our collective intention for this article – our artistic expressions along with our written contributions – demonstrates the power of bringing together unique perspectives, talents, and passions toward this common goal.

Most importantly, we believe there are many ways to create change in schools, but if we want to create a change we need to follow our words with actions. We need to go beyond words. Not only do students have to help create a change, both the students and educators should come together to implement the changes they want to see within their school systems and communities. We believe in the power of the arts as one form of taking action. We have seen its power in our own lives and its potential to uplift our own and others’ identities, culture, and values.

SUGGESTIONS FOR GOING “BEYOND WORDS” THIS YEAR:

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers can take advantage of the disruptions to traditional, lecture-based, in-person learning to explore different styles of teaching and engaging with students, making more room for student choice and voice.

- Teachers can use the multiple modalities afforded by digital platforms to offer students more choice in terms of the media and languages they use to express their ideas. They can even use TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, etc. to meet students where they are.

- Teachers can leave space in the syllabus or time in class to talk about authors who aren’t White. For example, they can add poems or short stories of people who speak other languages and intertwine their language into their poems or stories.

- Teachers could create projects where the students are required to seek different authors/artists/singers from different countries and speak about their background while including some of their work; they can do this in order to broaden the students’ knowledge of authors/artists/singers who aren’t White or from the U.S.

- Students could advocate for diversity in the curriculum by going to their administrators and student board representatives and asking what can be done. Similarly, teachers can advocate for a more inclusive and diverse curriculum by working with administrators or petitioning the state.

[1]We capitalize White in this article following the lead of Eve L. Ewing (2020) in acknowledging that “it is a specific social category that confers identifiable and measurable social benefits.”

Albers P. & Harste, J. C. (2007). The arts, new literacies, and multimodality. English Education, 40(1) 6-20.

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Using and Choosing Books for the Classroom, 6(3).

Botelho, M. J. & Rudman, M. K. (2009). Critical multicultural analysis of children's literature: Mirrors, windows, and doors New York, NY: Routledge Press.

Burnaford, G., Brown, S., Doherty, J., & McLaughlin, J. (2007). Arts integration frameworks, research & practice: A literature review. Washington DC: Arts Education Partnership.

Callahan, R. (2005). Tracking and high school English learners: Limiting opportunity to learn. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 305-328.

Callahan, R., Wilkinson, L., & Muller, C. (2010). Academic achievement and course taking among language minority youth in U.S. schools: Effects of ESL placement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(1), 84-117.

Campano, G., Jacobs, K. B., & Ngo, L. (2015). A critical resource orientation to literacy assessment through a stance of solidarity. In J. Brass & A. Webb (Eds.) Reclaiming English Language Arts methods courses: Critical issues and challenges for teacher educators in top down times. 97–108. New York: Routledge.

de los Ríos, C. V. (2018). Bilingual Vine making: Problematizing oppressive discourses in a secondary Chicanx/Latinx studies course. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(4), 359-373.

Ewing, E. L. (2020, July 2). I’m a Black scholar who studies race. Here’s why I capitalize ‘White.’ Medium. https://rb.gy/6yrsuj

Flores, T. T. (2018). Breaking silence and amplifying voices: Youths writing and performing their worlds. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 61(6), 653-661.

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149–171.

Gonzalez, A. L. (2010, June 9). Life in Spanglish for California's young Latinos. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/10209213

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Gadsden, V. L. (2008). The arts and education: Knowledge generation, pedagogy, and the discourse of learning. In G. Kelly, A. Luke, & J. Greene (Eds.), Review of Research in Education, 32, 29–61.

García, Ofelia. 2009. Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Malden, MA and Oxford: Basil/Blackwell.

García, O., & Leiva, C. (2014). Theorizing and enacting translanguaging for social justice. In A. Blackledge & A. Creese (eds.), Heteroglossia as practice and pedagogy. Dordrecht: Springer.

Johnson, L. L., Gibbs Grey, T. D., & Baker-Bell, A. (2017). Changing the dominant narrative: A call for using storytelling as language and literacy theory, research methodology, and practice. Journal of Literacy Research, 49(4), 467-475. Klapicová, E. H. (2017). Social aspects of code-switching in bilingual children. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics, 14(2), 35–46.

Martinez, D. C. (2017). Imagining a language of solidarity for Black and Latinx youth in English language arts classrooms. English Education, 49(2), 179–196.

National Museum of the American Indian Educational Office (n.d.) Boarding schools: Struggling with cultural repression. https://rb.gy/ddcbmz

Vasudevan, L. (2016). Arts, media, and justice: Multimodal explorations with youth. New York: Peter Lang. Official report of the nineteenth annual conference of charities and correction (1892), Reprinted in F. P. Prucha (Ed.), 1973, Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the “Friends of the Indian” 1880–1900, (pp. 260–271). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Orellana, M. F., Martinez, D. C., Lee, C., & Montaño, E. (2012). Language as a tool in diverse forms of learning. Linguistics and Education, 23(4), 373–387.

Phillips, C. (2019). Students challenge negative perceptions of spanglish. Morning Edition, NPR. https://rb.gy/kgwwia Sayer, P. (2008). Demystifying language mixing: Spanglish in school. Journal of Latinos & Education, 7(2), 94–112.

Tatum, B. D. (2000). The complexity of identity: “Who am I?.” In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W. J., Hackman, H. W., Zuniga, X., Peters, M. L. (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice: An anthology on racism, sexism, anti-semitism, heterosexism, classism and ableism (pp. 9-14). New York: Routledge.

Weltsek, G., & Koontz, N. P. (2018). Subversive literacy: Arts-based learning for social justice, equity, and student agency. English Journal, 107(6), 61-68.

Whitelaw, J. (2017) Arts-based literacy learning like “New School:” (Re)framing the arts in and of students’ lives as story. English Education, 50(1). 42–71.